This weekend I took a trip on the Empire Builder train to Leavenworth, Washington to see the Christmas lighting ceremony the Bavarian-themed town performs each day to adoring crowds from around the region. Riding Amtrak provided a fun alternative to braving the mountain pass in a car. The return trip was a sightseeing adventure in its own right, the lanky pines bearing a heavy coat of fresh snow.

That said, the trip still left much to be desired. The biggest drawback: the train is slow. The return trip to Seattle was scheduled to take four hours and ended up taking almost five after a few track delays. On a good day, driving with no traffic takes 2 hours and 20 minutes. To me, it highlighted the need for passenger rail improvements and a long-term vision for a national network of high speed rail.

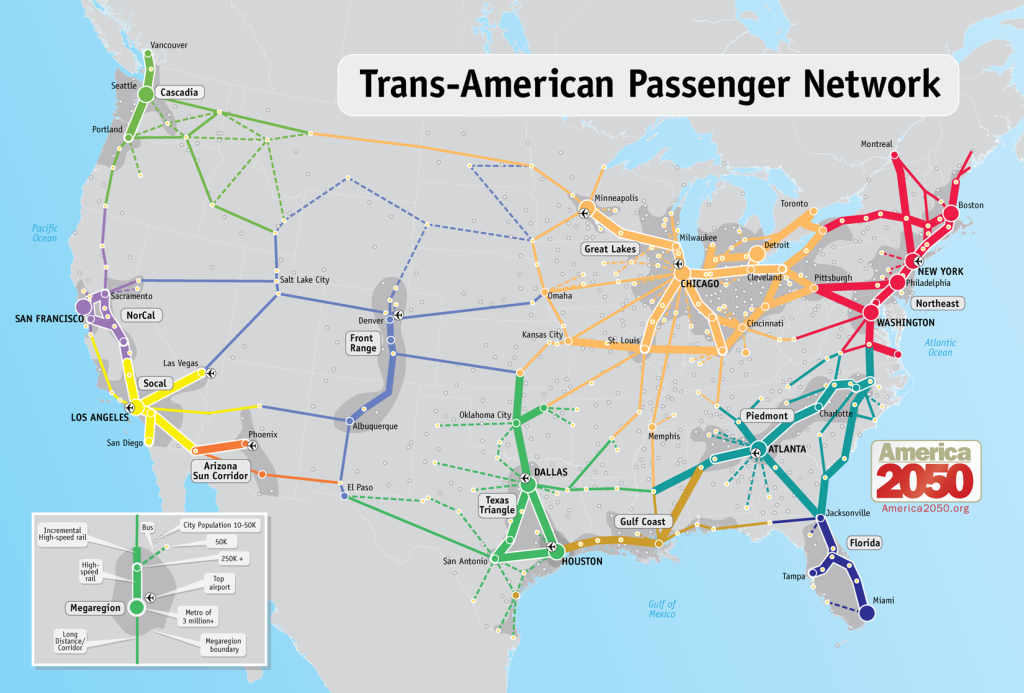

Luckily, many dreamers have been here before me. Artist Alfred Twu devised the map below in 2013 which seems a solid dream scenario map even if the details are debatable. Twu’s likely overly optimistic math was that if United States built the 20,000 miles of high speed rail over thirty years (667 miles per year) it’d only cost $40 billion per year or about 1.1% of the federal budget (at $60 million per mile). No one said visionaries had to be fiscal conservatives, too.

The 2016 election was certainly messy and potentially catastrophic (given the climate change denial, sabrerattling, and white nationalism) but one thing to emerge from the chaos was sort of fractured consensus on boosting infrastructure spending. It’s hard to trust campaign promises, especially from a politician as inconsistent as our president-elect. However, the Republican-controlled Congress may actually take up an infrastructure bill. Alas, it seems all too likely Republicans will focus on highway expansion and won’t touch passenger rail with a ten-foot pole except perhaps to skewer it. That’s too bad because highway widening is a wholly ineffective transportation strategy, as Strongtowns’ Chuck Marohn once said:

“Trying to solve congestion by making roadways wider is like trying to solve obesity by buying bigger pants. You’re not really getting at the fundamental problem that’s going on.” – Chuck Marohn, President of Strongtowns

Even with the bad signals coming from the incoming administration, the American electorate seems intent on improving infrastructure; I think rail advocates and progressives intent on jump starting the economy with wise investments could eventually sell the idea of high speed rail. The trend that is making high speed rail a necessity is none other than the climate change Republicans so shamelessly deny. Air travel is very carbon intensive, as Elisabeth Rosenthal wrote in the New York Times:

For many people reading this, air travel is their most serious environmental sin. One round-trip flight from New York to Europe or to San Francisco creates a warming effect equivalent to 2 or 3 tons of carbon dioxide per person. The average American generates about 19 tons of carbon dioxide a year; the average European, 10.

So if you take five long flights a year, they may well account for three-quarters of the emissions you create. “For many people in New York City, who don’t drive much and live in apartments, this is probably going to be by far the largest part of their carbon footprint,” says Anja Kollmuss, a Zurich-based environmental consultant.

Ultimately air travel being carbon intensive means it will also be expensive. A carbon tax will drive up the cost of aviation fuel making rail travel more competitive since planes are fuel-intensive and cannot be electrified and trains are less fuel intensive and can be electrified. Washington state was 9.25 percentage points short of passing a carbon tax. A better crafted bill may very well succeed. Even if a national carbon tax doesn’t happen, the cost of petroleum (and thus aviation fuel) inevitably will rise since it’s a finite resource feeding a growth-based global economy. The supply is limited. The demand seems endless.

The Obama Administration’s Approach

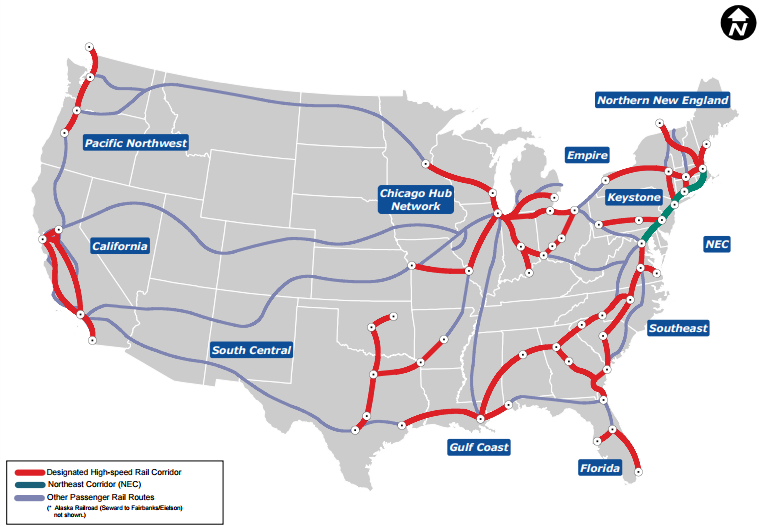

Alfred Twu’s plan drew flak for being too unrealistic and expensive. In 2009, the U.S. Department of Transportation’s Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) published its vision for a high speed network with fewer long distance high speed routes. The FRA and other experts argue the sweet spot for high speed rail is trips ranging from 100 to 600 miles between large cities. Beyond 600 miles, air travel is thought to have too big of a time advantage. This makes sense for 2016, but will airfares hold steady and will some consumers seek a carbon-light alternative to lower their carbon footprint?

While Twu’s plan took criticism, there are a few headscratchers on the more conservative FTA map. Why not connect Dallas and Houston, Texas’s largest metropolises? Why not add high speed rail between Cleveland and Pittsburgh so that the Chicago Hub Newtork and “Keystone” Northeast Network connect. A more staid think tank called America 2050 has their own three phased plan for expanding high speed rail with a fancy map graphic.

President Obama actually put some money behind the plan: $8 billion in stimulus dollars. Unfortunately, his high speed efforts were thwarted by Republican governors and legislatures that moved to block approval. Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker infamously prevented my former city of Minneapolis of connecting with Chicago via Milwaukee. (If only Wisconsin didn’t stand between Minnesota and Chicago…) Florida Governor Rick Scott denied Obama’s efforts to connect Tampa and Orlando with high speed rail. Thus, despite a sizable stimulus package following the economic crash in 2008, funds were denied to our rail network.

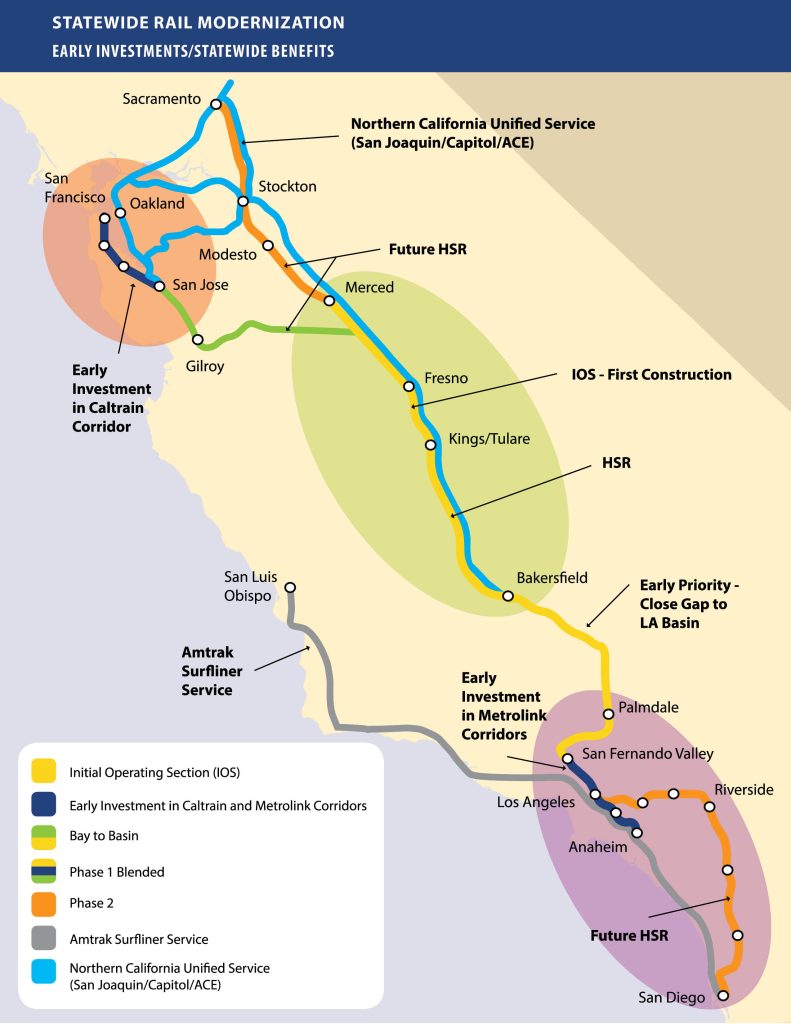

California Dreams Becoming Real

Nonetheless, we are making progress in fits and starts. California is in the process of building high speed rail between Los Angeles and San Francisco. The line which is expected to offer a top speed of 220 miles per hour and be finished by 2029 with smaller segments opening earlier assuming everything goes according to plan. The second phase of the California high speed rail plan would extend service north to Sacramento and south to San Diego.

Acela Corridor Upgrades

In the Northeast, the Acela corridor from Boston to Washington, D.C. offers the fastest service in the Amtrak network. The Acela Express section from New York City to D.C. allows maximum speeds of 150 miles per hour although the average speed is 82 miles per hour with intermediate stops. The Obama administration won further improvements to the Acela corridor both in the otherwise pretty flawed transportation bill it shepherded through Congress in 2015 and sped them up by issuing a $2.45 billion loan in August to upgrade the trains to the next generation of Alstom sets with a top speed of 186 miles per hour. Those faster trains are due to go in service in 2021 (although tracks in many stretches would need further upgrades to allow the top speed).

The Obama administration left another parting gift to rail advocates: modifying federal rules to be more friendly to faster passenger rail service. Specifically, it changed safety requirements for rail allowing trains to be lighter, faster, and more efficient and still share track with freight rail. American trains are heavy, overbuilt and slow compared to more light and nimble European counterparts. The new standard signals a new focus on crash avoidance rather than crash survivability (essentially armor), and it will cut down on costs because America can now use popular European and Asian models rather than buying tank-like trains built with tons of excess steel specifically for the quirky American market. This is an important hurdle to clear in making a national high speed rail network viable.

Texas Bullet Train

Meanwhile, a private company is seeking to bring bullet trains to Texas with high speed service between Houston and Dallas. The company believes it could run the $12 to $18 billion line at a profit but it has run into a snag acquiring the property. The Fort Worth Star-Telegram laid out the eminent domain issues which could be a common obstacle in any plan to expand high speed rail right-of-way and make real high speed hopes:

In its quest to accumulate land, the company cites a state law dating to 1876 that allows a railroad to take private land in Texas for the public good, even if the railroad itself is a for-profit, private company. Such laws have been used for decades by electricity providers, river authorities and oil and gas pipeline concerns to acquire property through eminent domain.

But Risinger and about three dozen other property owners situated between Dallas and Houston who have been slapped with similar lawsuits argue that the law was never intended for a bullet train.

The lawsuits are just the latest twist in the effort to build what could be the nation’s first truly high-speed rail line. Using technology from Central Japan Railway Co., trains capable of traveling 205 mph would leave stations in Dallas and Houston about every half hour.

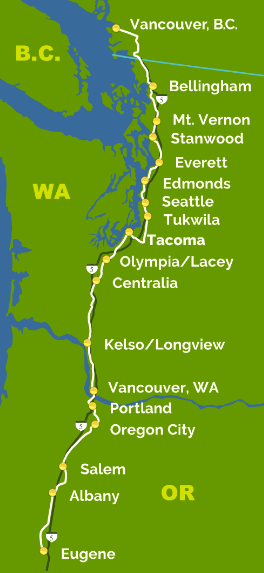

Cascadia Express

Closer to home, King County Executive Dow Constantine made some headlines earlier this year for an event at which he promoted high speed rail to British Columbia. Just 142 miles (229 kilometers) separate the two booming city centers meaning a high speed train could cut travel time to less than an hour, making rail the preferred option for most considering the added time of getting to an airport and making it through security. One study suggests that the line would cost $30 billion, although other estimates have been lower.

On the other end, 173 miles (278 kilometers) separate downtown Seattle and Portland and it would cost about $20 billion to connect the two with high speed rail, according to Brad Perkins who is CEO of Cascadia High Speed Rail, a company seeking to do just that. It’s a steep price tag but perhaps the spectacle of one hour train rides to Portland not mention big carbon reductions would entice the states of Washington and Oregon to make the investment.

Amtrak Cascades continues on to Eugene, roughly 110 miles (177 kilometers) which could also be upgraded to high speed with an additional investment. That would lead us to the biggest chasm a West Coast high speed rail corridor would have to cross: the 474 lonely miles (763 kilometers) between Eugene and Sacramento, which is the farthest north California’s high speed rail system is planned to go. At $60 million per mile, the 474 mile gap would cost $28 billion to bridge, but maybe the result would eventually be worth it. Seattle to Los Angeles by transit would go from 31 hours to six hours (if the train can average almost 200 miles per hour.) Even a flight takes three hours plus all the hoopla at the airport, so it seems high speed rail could compete with air travel by being slightly slower but more comfortable, cheaper, and terminating in a city center rather than on the urban fringe.

It’s harder to envision coast to coast high speed rail, at least without massive federal intervention. Connecting Los Angeles and Las Vegas isn’t so daunting but from there its 748 miles to Denver and another 1,004 miles to Chicago. From Chicago it’s 697 miles to Washington, D.C. or 790 miles to New York City (via straighter interstate right-of-way.) That means LA to NYC would be about 2,800 miles of track and take 14 hours if an average speed of 200 miles per hour could be maintained. It’s not nearly as speedy as air travel but it might be only the only option many Americans can afford if rising fuel prices drives airline travel beyond their means. In addition to the flashy high speed rail between the big cities, more incremental improvements to Amtrak service to smaller cities would help a wider swath of America and feed into the high-speed mainline service.

At first, it’s likely that regional high speed networks will develop like the one that already slowly working its way to high speed in the Northeast and California’s network that’s under construction. However, the Federal government might eventually see the wisdom in connecting the regional high speed networks to build some sustainability into our transportation network. It’d probably make more financial sense than highway expansion. We can’t keep burning carbon forever.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.