Often when an idea comes along that the urban planning world finds intriguing, there’s a race for other cities to try out that idea. One such idea that has been getting a lot of press lately is the Barcelona “superilles“. In English, this word is being translated as “superblock” but Americans have their own idea of what a superblock is: a large block, often with a single building, that breaks up the street grid, a large impediment that requires getting around. Key Arena is a superblock, though I won’t be arguing for tearing it down in this article.

A superille is quite the opposite. A superille takes what is currently there and transforms it. From the New York Times:

Under the plan, the superblocks will be overlaid on the existing street grid, each one consisting of as many as nine contiguous blocks. Within each superblock, streets and intersections will be largely closed to traffic and used as community spaces such as plazas, playgrounds and gardens.

In other words, prohibit almost all vehicles from quiet residential streets, and “grow” the blocks between major car routes. Another reason that superblock is not quite apt is that it implies streets are primarily for the benefit of pedestrians and cyclists are not really streets. In reality, while superblock implies a greater distance between two points, a superille actually will shrink neighborhoods, allowing homes and businesses to be a quicker trip away. Apart from distance, the biggest determinant of travel time is how many major arterials you cross to get where you’re going.

But I want to talk about some of the ways in which Seattle streets are partly on the road to having some of the same features as a superille, even if it’s not being done on the same scale. By recognizing aspects of this transformation on our city streets, we can push for more of the same features as the opportunities become available.

Josh Feit at Seattle Met recently reported the jaw-dropping fact that nearly 11% of Seattle commuters, 43,000 people, commuted via foot in 2015. This 50% increase from 2010 levels is really a stunning fact that begs the question: is Seattle infrastructure able to handle all of those pedestrians? And how could it work better for everyone?

Pedestrian Streets

The closest term that can be used in Seattle right now to the superille is pedestrianizing. And it has been as much a buzzword as the Catalan counterpart over the past few years. But it too can be misleading, or at least misused.

Bell Street is probably the best example of a “pedestrianization” project that failed to achieve its intended purpose. The transformation of Bell from 5th to 1st Avenues into a curbless boulevard with bioswales and built-in seating areas has a number of weak spots: unenforced signage means that traffic diversion is nonexistent, and combined with the routing of several bus routes down Bell Street means that pedestrians are wise to stick to the sides of the street, maintaining the separation of street and sidewalk much as before. In addition, nominal improvements were made to the facilities crossing the avenues, so there isn’t much reason to claim any extra pedestrian space when you’re back to hugging the sidewalk at the next street crossing.

The response on bus routing from SDOT has been that buses need to remain on Bell Street until the reconnection of the street grid after the opening of the SR-99 tunnel. Perhaps at that point we can get serious about traffic diversion and convert more of the on-street parking into seating and amenities.

But there are a number of projects which are in progress that I want to highlight that present just as much of an opportunity as Bell Street does for pedestrian-orienting our streets.

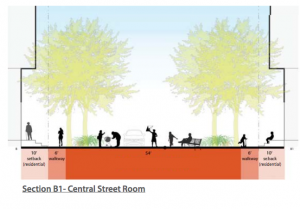

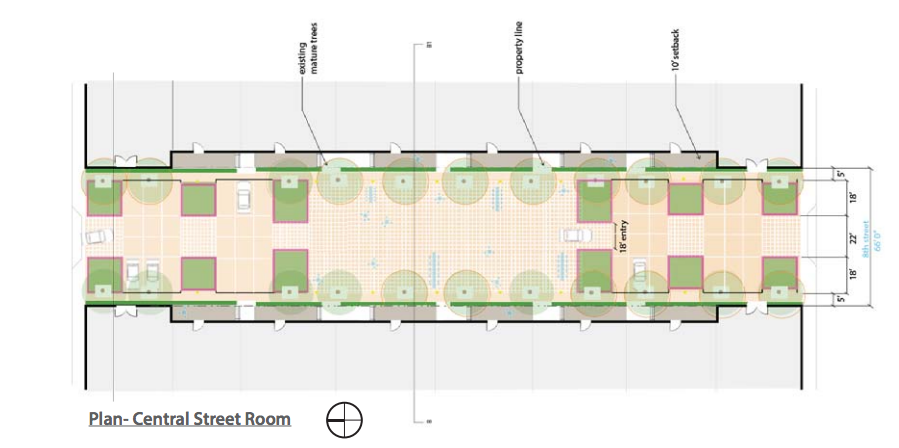

The 300 block of 8th Ave N (between Thomas and Harrison) will be home to two office buildings, facing each other on opposite sides of the street. Vulcan successfully lobbied the city to allow them to add some pedestrianizing features that will calm the street. 8th Ave N is a really tucked-away street in South Lake Union currently, but could provide a great calm route for residents and workers in the neighborhood to get from points south via Denny Park, which is its own “superblock” with diagonal paths cutting across it, providing a nice shortcut to Dexter and 9th/Westlake.

Pedestrianizing a street does not intuitively pair with 24-hour on-street parking. Parking spaces are not at a long-term premium in South Lake Union, as we have written about time and time again at The Urbanist, and on-street parking creates a demand for vehicles to use the street. When the City Council approved a waiver allowing Vulcan to avoid paying additional fees to create the green street, Councilmembers Mike O’Brien and Kshama Sawant objected, on the grounds that the deal appeared to be a corporate giveaway. Making sure that the public street becomes the best pedestrian and bike corridor that it can is one way that equity and full public access is ensured.

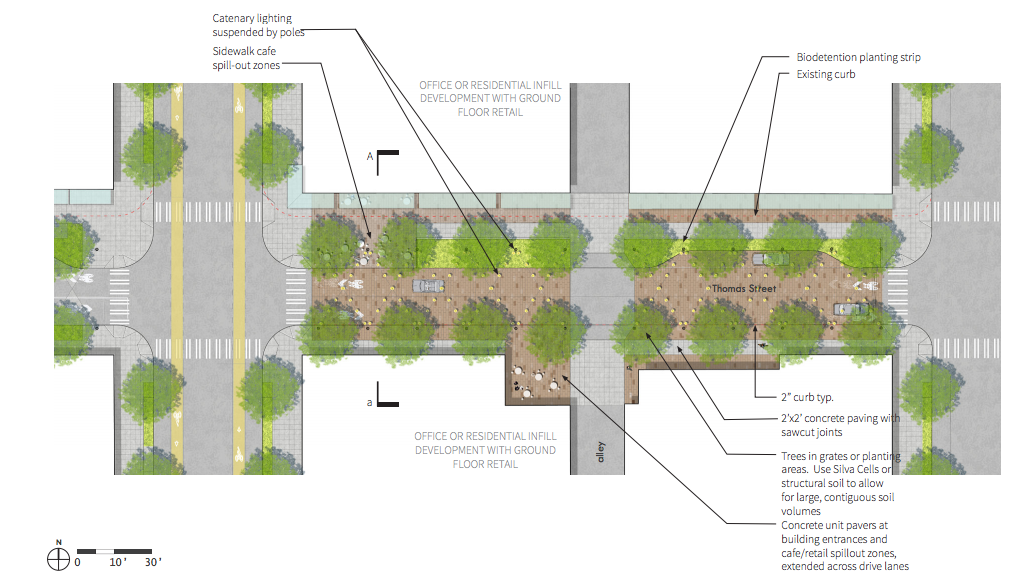

The 8th Ave N street looks even better when paired with what could be a game changer for people on foot and on bike in north Downtown Seattle. Thomas Street is proposed as a neighborhood greenway between Seattle Center (once a connection across Aurora is re-added) and the other side of South Lake Union (and, pie in the sky dreamers like me say, a pedestrian-only bridge over I-5 to Capitol Hill and the Melrose Promenade).

The Lake2Bay project, an offshoot of the Seattle Parks Foundation, envisions a pedestrian-oriented route from Lake Union to Elliott Bay through the Seattle Center. The Thomas Street section is crucial, as it provides an opportunity to create a truly-pedestrian oriented street in South Lake Union that will serve to divert traffic off the entire greenway corridor. That is, Thomas Street should be entirely closed to cars, except for the purposes of loading, for at least one block.

The model here is of course Occidental Avenue S between Main and Jackson Streets, which was converted into a pedestrian block due to the work of Allied Arts, which R. M. Campbell detailed in his book Stirring Up Seattle: Allied Arts in the Civic Landscape. While some, myself included, find that Occidental is often overrun with cars using the space for parking on the weekends, there isn’t really any issue with drivers going too fast on the street. It is clear pedestrian space, through and through. This is achieved through the use of bollards at one end of the street, prohibiting through-traffic.

For five years between 1990 and 1995, Occidental Ave had a northern Downtown counterpart in Pine Street between 4th and 5th Ave. But in 1995, voters were persuaded to reopen the street to traffic for the benefit of the downtown business district, which was going through a tough stretch with the departure of Frederick & Nelson from the current Nordstrom flagship location across 5th Avenue.

It’s almost hard to believe that the throngs of pedestrians traversing the distance between Westlake Park, Westlake Mall, and the monorail once held full reign over the street here. But it certainly makes the case that Seattle once knew exactly what a “superblock” was–and might be able to see the benefit of bringing them back. The sheer numbers of people on foot in Downtown Seattle suggests it’s worth a try.

In part two of this series, we will look at other ways that blocks can be brought closer together and the pedestrian realm improved.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.