When I published an argument for removing I-5 from central Seattle on Monday, I hoped it would start a conversation, and it does seem to have gotten some traction. Charles Mudede added a think piece for The Stranger. Capitol Hill Seattle blog summarized my case here. Shrill KIRO talk radio host Jason Rantz even got wind of it and, true to form, worked it into a rant that isn’t worth a hyperlink. And below, even Knute Berger added a cryptic tweet. I’ll take it!

We should bring back Denny Hill too. https://t.co/HyXLGuVjnI

— Mossback (@KnuteBerger) November 3, 2016

I also got a lot of negative feedback. I will respond to some of the more constructive bits in the following

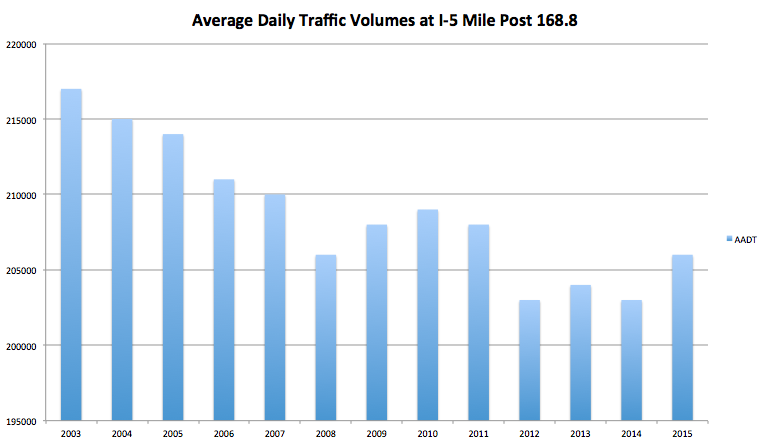

Downtown I-5 Traffic Counts Are Flat

This may come as a shock to some people but Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) data shows that Downtown I-5 annual average daily traffic (AADT) is actually down from where it was a decade ago. In 2005, the AADT was 214,000, while in 2015 it was 206,000.

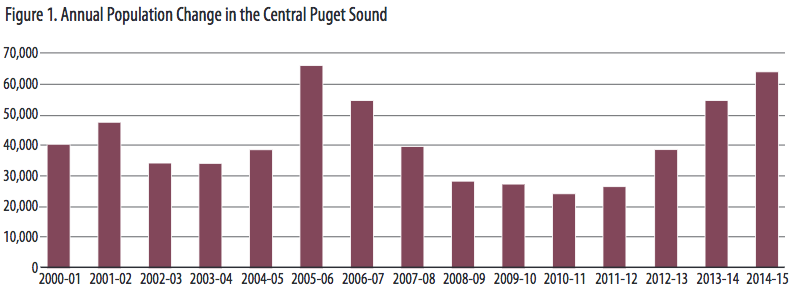

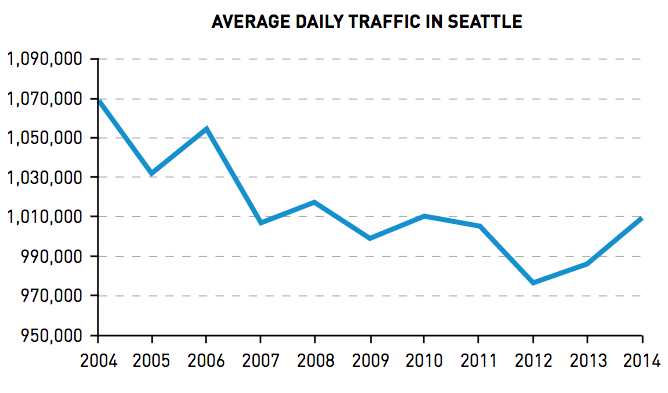

This is all while the region added hundreds of thousands of residents over the last decade. We’ve grown rapidly, but traffic counts on I-5 in Downtown have actually decreased over that timeframe. An armchair transportation planner (perhaps even WSDOT professionals and their models) might expect adding residents would mean adding traffic Downtown but that doesn’t seem to be how it’s necessarily worked.

Seattle proper had a population of 563,374 in the 2000 census, 608,660 in the 2010 census, and the Census Bureau estimates the population reached 684,451 in 2015. Despite adding more than 100,000 new residents, Seattle had greater average daily traffic counts in 2004 than it does now.

Understanding The Lived Experience Of Traffic

Now, the lived experience of traffic is still terrible. I never disputed that and was reminded many times it was. But this is why restoring the street grid Downtown might actually make things better. Freeways are brittle. Too much traffic equals gridlock and no means of escape until the next exit. When you are driving on a grid of city streets, you can’t achieve the same top speed but there are options; when one route becomes congested, you simply make a couple turns and select another. You can even say the heck with it and find a place to stop and say order a pizza. Unlike a certain TV commerical by a certain freeway-fetishizing gubernatorial candidate, you can actually obtain a pizza when traveling on a city street. This is why–for me at least–the lived experience of rush hour on a city street grid is less suffocating than rush hour on a freeway.

Planning With Transit In Mind

One ever so helpful tweeter also reminded me that I-5 carries more traffic than Link does. After the U-Link extension, light rail carries 68,000 riders per weekday on average while as the graph shows above I-5 carries just over 200,000 vehicles, most of them single occupant vehicles, downtown. The added context though is that Sound Transit projects its system will carry 350,000 riders–the majority of them on the Central Link shadowing I-5–once ST2 is built out. That would put light rail on par with I-5 as a mover of commuters downtown. And if voters approve ST3 this November, Sound Transit projects 600,000 riders on light rail alone (likely a conservative estimate itself).

Changing The Social Contract

But I-5 also carries buses, some argue. Why disrupt those patterns? Here’s where reimagining I-5 gets really exciting. The land created would be a sort of blank slate. We can use some of the land to create a slimmer street with transit prioritized so that buses like the ones coming across SR-520 can still continue downtown efficiently. And in the process it would grow the usable boundaries of Eastlake, South Lake Union, and First Hill. Transit would be put next to destinations rather than on a closed freeway, and we could add protected bike lanes to boot to make a true multimodal “Compete Street,” a concept nearly every city adopts as a best practice but rarely actually uses. The possibilities are endless once we free ourselves from the hold of the idea of having freeways through urban cores.

Gaining More Than We Lose

Many people agreed with me that plowing I-5 through Downtown Seattle was a mistake (and that list includes President Dwight Eisenhower who approved the Highway Trust Fund in the first place). However, when it comes to correcting the mistake they stop short. People are used to the Downtown freeway connection now, and to some, the feeling of loss is stronger than the feeling of gain, even if a logical analysis suggests the gain is greater than the loss.

Other Cities Have Successfully Removed Freeways

Supporters were helpful with support of places that have taken urban freeways out of their cores. Rochester, New York is removing the freeway loop that hems in its downtown. San Francisco tore down the Embarcadero freeing its downtown waterfront. And Seoul famously removed the Cheonggyecheon Expressway and turned it back into a river (the Cheonggyecheon) surrounded by a linear park. Land values jumped, the park turned it a major destination, average temperatures near the park dropped 6.5 degrees in the sweltering summers, and city-wide traffic didn’t get noticeably worse. Removing the freeway also removed a source of induced demand.

Induced Demand

Speaking of induced demand, the evidence is strong to support this theory. Here’s what I wrote in a post from last year:

In 1968, mathematician Dietrich Braess formulated what became known as Braess’ paradox: in a congested road network, the addition of a new route will increase overall travel times. Seattle Urban Mobility Plan said the paradox can also be expressed as “the theory that direct routes often function as bottlenecks, and so reductions in total capacity can reduce congestion.” Cities have seen results that support the conclusion. Seoul saw traffic volumes decrease and property values go way up after it demolished Cheonggye Expressway, its downtown highway viaduct, and replaced it with a linear park. Stuttgart, San Francisco, Portland, New York, and Milwaukee have seen similar results when tearing down urban freeways.

It’s overarching reason is why we can’t use highways to build our way out of our traffic woes. People often cite geography as why Seattle can’t add more freeways, but actually, even if we could, new freeways would likely do more harm than good according to induced demand and the Braess paradox. Conversely, removing our central freeway (I-5 in Downtown) might actually improve traffic flows.

Taking Climate Change Seriously

Finally, I’ll conclude with perhaps humankind’s greatest challenge going forward: climate change. Transportation is the number one source of carbon emissions in Washington state. Plan Washington described the situation: “The majority (54.5%) of carbon emissions in Washington come from transportation via the consumption of gasoline and diesel in on road vehicles. Compare this to the national landscape, where a mere 33 percent of emissions come from transportation, and the electric sector takes up more then twice as large a portion.” Continuously prioritizing automobiles only furthers our dependence and fails to address our number one carbon pollution source. Electric cars would lower their carbon footprint, but even electric cars running on renewable energy still face the problem of embodied carbon, the carbon required to build the vehicle, and the carbon to transport it to the consumer. The Guardian suggested the embodied carbon of car may even be greater than its total tailpipe emissions.

The upshot is that – despite common claims to contrary – the embodied emissions of a car typically rival the exhaust pipe emissions over its entire lifetime. Indeed, for each mile driven, the emissions from the manufacture of a top-of-the-range Land Rover Discovery that ends up being scrapped after 100,000 miles may be as much as four times higher than the tailpipe emissions of a Citroen C1.

Now this study may be extreme, but even conservative estimates of embodied carbon suggest it’s equivalent to years worth of tailpipe emissions. And alas the embodied carbon of hybrids and electric cars is generally higher than conventional cars because building of the carbon intensive batteries. As Forbes reported, “The Union of Concerned Scientists did the best and most rigorous assessment of the carbon footprint of Tesla’s and other electric vehicles vs internal combustion vehicles including hybrids. They found that the manufacturing of a full-sized Tesla Model S rear-wheel drive car with an 85 KWH battery was equivalent to a full-sized internal combustion car except for the battery, which added 15% or one metric ton of CO2 emissions to the total manufacturing.”

We don’t have to outlaw single occupant vehicles, but we do have to reassess their priority in our transportation system if we want to grapple with climate change. Freeways through urban cores are counterproductive to any reasonable long-term carbon reduction strategy.

What’s Better Than A Lid? Remove I-5 Entirely From Central Seattle

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.