This post has been updated to reflect that Alan Durning retracted the comments on his personal blog regarding Sound Transit Regional Proposition 1 (aka ST3). Durning, though Executive Director of Sightline Institute, was not speaking on behalf of the institution in his personal blog comments, which I should have made clearer. I do humbly suggest that Sightline Institute going forward take a more active role in advocating for transit packages in the Seattle area as they do have a great deal of respect in the community–and rightfully so–and their influence would certainly help.

The Seattle urbanist community got a little surprise this weekend when Alan Durning–who is Executive Director of Sightline Institute–criticized ST3 on his personal blog which cast some doubt over whether ST3 was a solid package for the environment and mitigating climate change specifically. Sightline is a think-tank specializing in environmental sustainability but it hasn’t weighed in on the regional transit package that I have seen. In response to criticism of ST3’s climate change bonafides, I must reiterate that ST3 is a huge step forward for carbon reduction and more sustainable land use. Passing ST3 would be a big win for the environment, especially compared to the backtracking or inaction likely if it fails. That’s why The Urbanist endorsed ST3 in our general election endorsements.

The Freeway Trench Argument

Critics have highlighted a weakness of the plan in that several of the stations are built on or directly adjacent to freeway trenches which decreases their walkshed and the desirability of the land they open up for urban development. Valid point, but not reason enough to scrap the largest transit boost in Seattle history. It also overlooks that the Ballard and West Seattle lines will not be in freeway trenches. Things can be done like freeway lids and sound walls to mitigate some of the harm freeways do. And problem of traffic-related air pollution–a huge concern today–should become less acute as electric cars and trucks become a larger share of the vehicles on our highways.

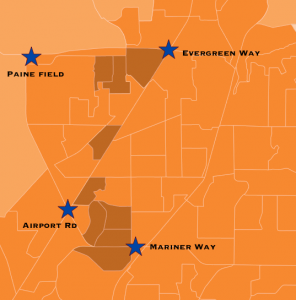

It’s also worth noting, for instance, that some of the most promising Snohomish County stations are not in the I-5 freeway trench in part due to the controversial Paine Field deviation. Plus, the Snohomish station areas are already fairly dense in contrast to Durning’s portrayal of them as hopeless suburban wastelands. One of the census block groups near the proposed Mariner Way station had a density of 18,534 people per square mile in 2012. That’s respectable density even for Seattle. All told, census data suggests somewhere in the neighborhood of 10,000 people live within the half-mile walkshed of Mariner Way station. That’s a dense neighborhood for 2012, and it will be even more so by 2030’s when the station is operational.

The Paine Field alignment not only put the Mariner Way station more squarely in the middle of a dense multi-family area, it also put Evergreen Way station in the more salvageable SR-99 corridor rather than I-5, as would be the provisional Airport Road station. And just to the south, 164th St SW (the sometimes ridiculed Ash Way station) has seen a huge boom since 2012 and may even overtake Mariner Way’s density by the time light rail arrives.

It’s important to remember most cities have been good at zoning for growth and vibrant urban districts near stations. Shoreline (145th St and 185th St) and Lynnwood already have implemented pretty aggressive rezones ahead of Link’s next northward expansion by 2023. Bellevue and Redmond have ambitiously rezoned ahead of East Link’s 2023 opening. And to the south, Kent passed design guidelines back in 2011 setting up urban-style zoning for its Midway neighborhood station scheduled to open in 2023, whereas Des Moines went so far as to enact 55-foot height minimums around the same station, which it will share. If ST3 passes, similar rezones are likely in Everett, Federal Way, Tacoma, and Issaquah. The area just below the proposed S 272nd St station (near Redondo Square) was the densest census tract in South King County in 2012 with 8,032 people in 0.787 square miles. The Federal Way Transit Center, on the other hand, isn’t as dense now but is well suited for an urban revitalization and a downtown type treatment.

Light rail is the kick municipalities need to think big and have confidence they can serve the transportation needs of their future citizens. Saying yes to ST3 sets the whole region on a much better land use pattern trajectory for decades to come. Trying to start from scratch piece by piece does not lend lawmakers that kind of certainty and confidence and could leave us with worse land use habits for much longer. Seattle can’t take all of the region’s population growth–projected to be more than a million by 2040–even if we tried. We need the suburbs to urbanize, too.

The Education Argument

Critics have also often cited State Senator Reuven Carlyle’s infamous dissent on education funding worries, an argument with which we already had serious issue. Carlyle’s sterling reputation does not mean Ballard’s beleaguered legislator is right this time. We can fund both education and world class transit. There is room within our property tax limits and the people’s appetite for further property tax hikes is a separate issue, especially considering the regional property tax authority is one of the few funding sources the State Legislature (with Carlyle’s voting all along in the process) gave Sound Transit. Now legislators are criticized what they themselves put on the menu.

Not Worthy Of Rail Argument

The intersection equity and rail-worthiness arguments is where the logic of some criticism really fell apart for me. On one hand, some argue places like Tacoma and Federal Way are not worthy of “prestige projects.” On the other hand, some of the same people call for greater equity for low-income communities. Do they not realize South King County and Pierce County include some of the most diverse areas in the region and have a large share of its low-income residents due in part to the suburbanization of poverty? For example, the Link extension to the Federal Way Transit Center will serve a population that is 57% minority and 22% low-income, according to Sound Transit, while the Lynnwood-to-Everett segment will serve a population that is 42% minority and 17% low-income.

For folks who cannot afford cars or choose not to own or operate them, ST3 is a huge mobility boost. They get a lot back in the form of faster, more frequent, and more reliable transit. A Harvard longitudinal study has also shown that commute time is the single strongest indicator of upward social mobility and escaping the cycle of poverty. As Seattle Subway has pointed out, more than 58% light rail riders make below the King County median income. Does the fact some might have to transfer to light rail mean they won’t use it? By and large, I think not. The fast ride to job centers like Downtown Seattle and the airport will entice a great many. We must remember that light rail—which will replace costly commuter bus service–will free up service hours for local bus service meaning transfers should improve due to boosted frequency and the likely expansion of bus service coverage. And if that’s not enough, let’s not forget that Sound Transit will be required to provide huge sums of excess property for affordable housing and already participates in a very progressive regional reduced fare program for low-income residents.

About That Climate Analysis

So the specific climate criticism argues that the 130,000 tons of carbon dioxide emissions reduction Sound Transit promises in 2040 for ST3 projects really is “negligible” or insignificant given that’s a fraction of overall projected regional carbon pollution. Critics have also suggested building all those lines will cause an enormous load of carbon pollution during construction and that Sound Transit didn’t factor in that construction-related carbon.

First off, I would respond that 130,000 tons of carbon dioxide per year from vehicle miles traveled is not negligible. Second, this is to say nothing of other potential knock-on carbon savings in housing and construction patterns, and other daily habits of transit-riding residents that will result from the switch to bus and rail. But the larger issue here is that Sound Transit ridership projections are conservative. Since Sound Transit was restructured, it has stuck to conservative projections and timelines to avoid the pitfalls of the earlier organization. That conservative caution means Sound Transit doesn’t factor future land use changes into its projections. Thus, it doesn’t factor in the zoning changes the region’s cities will make ahead of the 25-years worth of light rail and bus rapid transit projects.

Due to the zoning changes outlined earlier, station areas will likely be much more densely populated than in Sound Transit’s projection models. As a transit agency, it’s also not in the business of quantifying cascading effects such as the number of people who will forego car ownership given expanded light rail or move to neighborhoods where they almost never need to use a car. In short, I expect ST3 will save a lot more than 130,000 tons of carbon dioxide in 2040 and earn back its embodied carbon load many times over as its ridership grows and grows with the region. Imagine the difference ST3 will make by 2060. Over time, it will truly transform the region by guiding land use patterns and providing an increasingly enticing alternative to car commuting.

The Bus Argument

And finally no argument against ST3 would be complete without echoing the rumor that buses can provide the same quality service more cheaply. The Urbanist‘s Anton Babadjanov already challenged that BRT myth here. First of all, bus can approximate light rail service inexpensively only when it does not seek the same reliability and quality. Getting dedicated lanes, intersection treatments, high quality stations, electrifying or using battery powered buses… These things are all expensive.

Heidi Groover said it best in her definitive takedown of anti-ST3 arguments: “In 2005, Sound Transit studied both light rail and bus rapid transit with its own right-of-way between Seattle and Bellevue. They found that the costs would be similar and ridership would be higher on light rail. Buses have a role to play in mass transit, but they’re never going to do what trains can do.”

Really next level critics also suggests ST3 could accelerate sprawl by spreading light rail so far and building nearly 9,000 parking stalls. The parking stalls aren’t ideal but are still a small fraction of the total budget.

As far as accelerating sprawl, Seattle’s suburbs have already demonstrated a desire to break out of their sprawl habits as outlined above with urbanized zoning and land use changes ahead of light rail. And lest we forget, the Growth Management Act and regional VISION 2040 are extra insurance policies to greatly limit the ability of the powers that be to bulldoze rural, resource, and natural lands beyond for endless, unconnected tracts of low-density residential housing, but a “no” vote is a sure way to unravel all of that and add fuel to the cries to expand urban growth boundaries.

Let’s not do half measures with an 100-year investment. If we are truly focused on sustainability, we need to think in terms of longer time spans. That means Sound Transit’s cost-benefit analysis not showing ST3 as a net benefit for the region until 2071 is actually quite OK. We should be thinking in long time spans in order to fundamentally transform our economy away from fossil fuels and the suburban sprawl machine. The amount of urbanization for which even many critics advocate requires an ambitious transportation plan with long-term regional planning. Sound Transit delivered. We should not turn our backs now.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.