Central District residents filed into Washington Hall auditorium on Monday to hear about four mixed-use projects and focus on maximizing the community’s benefit from each. The event was named Imagine Africatown Update after the grassroots Africatown campaign that has emerged around Black empowerment in Seattle.

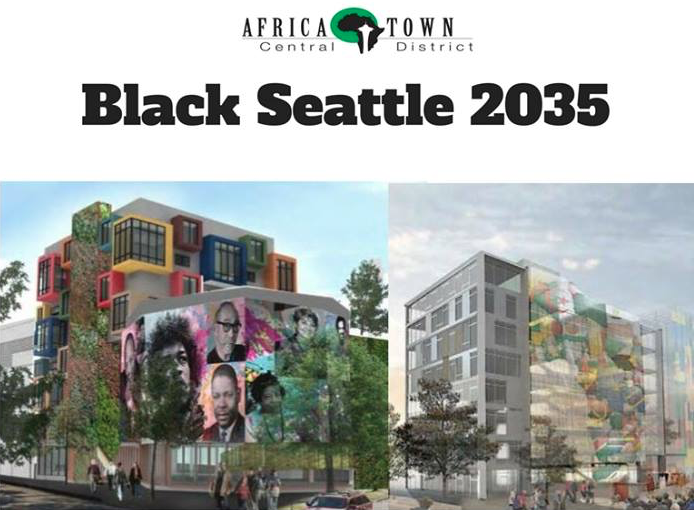

Thinking long-term, host K. Wyking Garrett said African-Americans must use opportunities like these developments present to reassert the African-American identity of the Central District and forge a stronger sense of place.

“If we don’t write ourselves into the future, there’s a good chance we won’t be in the future,” Garrett said. “There was intentional exclusion, and now we need to have intentional inclusion.”

Garrett said people forget Blacks still live in the Central District. The neighborhood has seen an influx of new development and newcomers, many of them white and well to do. Garrett was thinking perhaps of an article like Gene Balk’s column from last year announcing “Historically black Central District could be less than 10% black in a decade.”

“People are writing eulogies, but we’re still here,” Garrett said.

Changing Demographics And A Continuing Legacy

And while Balk’s research suggests a significant number have left, several thousand Blacks indeed still call the Central District home.

I analyzed demographic data for this narrow stretch of Central Seattle between 15th Avenue and 31st Avenue, roughly with Madison Street at the north and Judkins Park at the south. The census shows that in 1970, more than 15,000 blacks called this area home, making up 73 percent of the neighborhood’s population. By the 2010 census, the neighborhood had become majority white. Today, the number of blacks has dwindled to less than 5,000 — not even 20 percent of CD residents, according to 2014 estimates from Nielsen.

It’s also worthy to note the Central District has seen an influx of Latinos and Asian-Americans who make up about a quarter of the neighborhood’s population. The neighborhood may not be as Black as it once was but it’s certainly diverse. Also, side note, the woman Balk interviewed for the Central District perspective in his piece, Rosalie Johnson, was sitting right next to me at the meeting and was grilling Garrett about how the process would work. Rosalie Johnson saw redlining firsthand and overcame it as Balk explained:

Nearly all Seattle banks refused to provide loans or financial services to anyone who lived in the neighborhood, a practice known as redlining. “The banks wouldn’t lend you a penny,” Johnson says. “They redlined us in, but it backfired, because we thrived — beautifully.” She recalls the neighborhood as almost a city within the city, with its own economy. “We had our own doctors, lawyers, newspaper — everything.”

It wasn’t just mortgages and leases that were harder to come by for Blacks. City services weren’t always up to par. For example, Johnson and her peers helped fight to get a bus on 23rd Avenue, today’s Route 48 bus, which is one of the highest ridership lines in the system and is slated for RapidRide+ upgrades by 2024.

“Convenient? It wasn’t convenient for us back then,” she says, recalling some of the obstacles that people in the neighborhood faced. “Do you know how hard we had to fight just to get them to run a bus line down 23rd Avenue?”

Liberty Bank

The history of Blacks in the Central District goes back 130 years and the mission of the Africatown-Central District Preservation & Development Association is “to honor, preserve, promote and develop the legacy and presence of Black Americans and newly arrived Africans in Seattle’s Central District as a vibrant community and unique urban experience.”

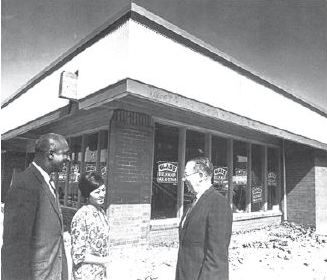

The event focused on the future of the Liberty Bank Building, a strong source of pride for many African-Americans due to its history as a Black-owned bank, the first west of the Mississippi. The bank no longer stands but the community remembers its important role and reached a memorandum of understanding (MOU) with Capitol Hill Housing to celebrate that history and make sure it lives on by doing the most possible good for the Black community. The MOU includes a route for the Black community to take over ownership of the property: “CHH will develop a partnership with Centerstone and Africatown that provides the opportunity for African-American community-based ownership of the building. Centerstone will have both a right of first offer and first right of refusal to acquire Liberty Bank after 15 years.”

Liberty Bank was founded in 1968 as a community response to redlining and disinvestment in Central Seattle. Its founders were a racially diverse group who recognized the need for financial resources in the predominantly African-American Central Area. The founding of Liberty Bank was a key milestone in the progress of the African-American community, and it provided much needed services until 1988.

The community felt it as a blow when Key Bank took it over and when the City declined to give the building historical landmark designation after Key Bank sold it in 2015, leading to its demolition. Some in the crowd still expressed frustration that the building that hosted the region’s first Black-owned bank didn’t warrant historical preservation. Nonetheless, Garrett presented Africatown as a forward looking movement seeking to harness the changes for good, and the extent to which Capitol Hill Housing was working with the community to maximize the project’s benefit to the Black community was certainly a step forward from how development has often worked in the past.

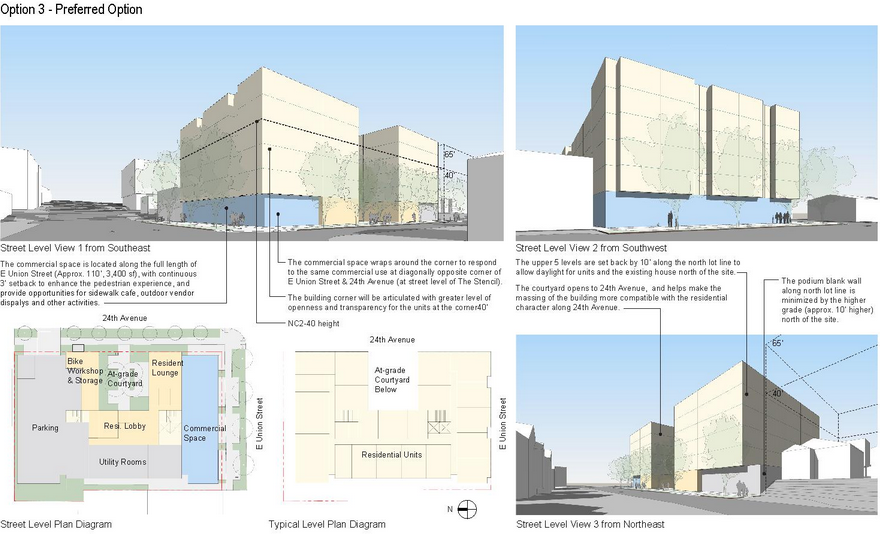

Capitol Hill Housing’s plan is to build a six-story building with 115 income-restricted apartments and 2,695 square feet of retail that will comprise four storefronts. The website promises “a 3,000 square foot rooftop deck with commanding views of the neighborhood and an outside courtyard on the ground floor” and secure indoor bike storage.

The units range from studio to two-bedrooms and are income-restricted and open to people earning between earning between 30% and 60% of the area median income (or between $31,650 and $54,180, depending on family size). Capitol Hill Housing’s representative said they want to help Blacks afford to live in Central District as it redevelops.

A Call For Black Construction Workers

One key takeaway of the Africatown meeting was to put out word to African American subcontractors and construction workers to put in bids. Garrett put it this way: “Sometimes the bus is gone when we get to the bus stop.” He stressed minority business get in their bids sooner than later as well as people just looking for a job as a laborer.

Capitol Hill Housing is aiming to generate as many jobs within the community as possible. Bill Reid who is general manager with Walsh Construction—the firm Capitol Hill Housing selected as the general contractor—said they will assist smaller firms to break up the contracts, formulate estimates, and to navigate the requirements of handling a city contract, such as certified pay roll and insurance. A Black-owned firm has already been selected to do the plumbing work. Capitol Hill Housing said they will break ground in June 2017. The project is an investment of more than $30 million, and apparently the dry wall contract alone would be worth more than a million dollars. So get those bids in!

For those interested in the Liberty Bank Building bids here is the contact information for the relevant parties at Walsh:

- Sandi Tovias, stovias@walshconstruction.com, 206.547.4008

- Chuck Holcom, cholcom@walshconstruction.com

- Dick Hutchison, dhutchison@walshconstruction.com

Empowering Black Business Owners

Africatown is also seeking input as to what businesses Black residents would like to see go into the Liberty Bank Building. The obvious choice is a bank—as a few participants point out—but Capitol Hill Housing explained that when Key Bank sold them the property below market value, it stipulated any bank going into the site would have to get its approval first. So, Key Bank might veto that effort. Garrett wasn’t discouraged and said if they fight for it they still might win approval for a financial institution to go in. Beyond a bank, Garrett said Africatown would favor businesses that foster community building and gave barbershops as an example. Africatown wants to gather community input to develop a rubric to grade proposals.

Black Artists Expressing Black History

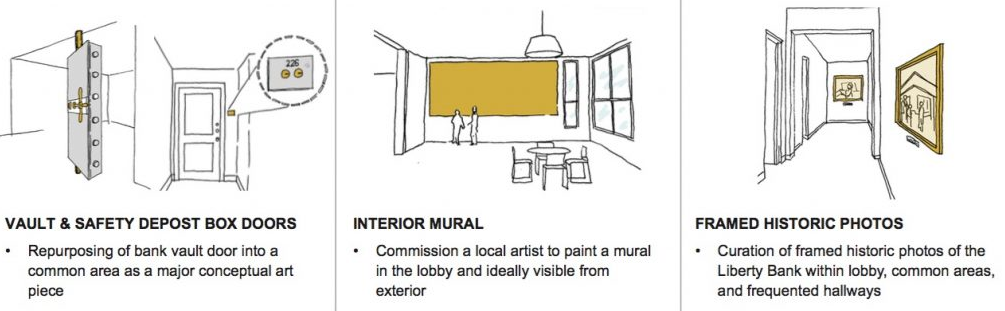

The building will also prominently feature art by Black artists Al Doggett and Esther Ervin as well as historical photographs, signage, plaques, and even re-purposing the bank vault as an art installation to honor the building’s history. The history Africatown seeks to express and the legacy it seeks to rectify goes beyond just Liberty Bank.

“This country was built in many ways on the backs of Black people’s labor and on Native American land,” Garrett said. “There’s no two ways about it.”

The Africatown gathering Monday also touched on three other Central District projects in the works: the YK building, Fire Station 26, and the Midtown Center.

YK Building

Catholic Housing Services is rehabilitating the YK Building at 110 14th Ave and will provide 34 single resident units restricted to those making between 30% and 50% of area median income. Work would begin this fall and conclude in January 2017 according to the plan. The primary opportunity here is affordable housing since there doesn’t appear to be a retail component.

Fire Station 6

Fire Station 6 is a decommissioned station at 23rd Ave and Yesler St. The aging building still stands, but the fire station relocated to a site nearby on Martin Luther King Boulevard. Garrett reported Africatown was working with the City to put the site to use for the community.

MidTown Center

MidTown Center at 23rd Ave and Union St is likely to see another big development and has been a center of controversy due to a preliminary plan that was portrayed as an effort to demolish minority-owned small businesses and replace them with luxury apartments. Africatown helped squash that deal and it fell through, but another deal seems imminent as Lennar Multifamily Communities has a proposal for a 405-unit project in the works. MidTown Center has the added drama of a inter-family legal squabble as Bryan Cohen reported:

The Midtown sale was put in motion last year after Tom Bangasser’s siblings voted to remove him as controlling member of Midtown Limited Partnership, which has owned the property for generations. He told CHS his siblings had grown impatient with his vision to transfer ownership of the property to a land trust that would come under community control. With Bangasser demoted, the siblings contracted realtors Kidder Matthews, which rolled out a slick website to help sell the property.

Africatown is seeking to own the site so new development is community-focused and Tom Bangasser would like to make that happen, too. The other Bangasser siblings were not onboard with that, but perhaps they will have a change of heart or get outmaneuvered in the courtroom.

The sum total of these projects could be very good for the neighborhood. Africatown shares the goal of more housing, especially affordable housing, and more spaces for small businesses to set up shop. However, Garrett also issued a warning that African-Americans must be agents of change in this changing neighborhood or the spirit of cooperation could not be guaranteed. Writing Blacks out of the future of the Central District was not an acceptable path for the development of Central District to Africatown activists.

“We get involved or we need a moratorium,” Garrett said.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.