Earlier this year, Senator Maria Cantwell announced that the largest grant ever awarded to the state of Washington would be going to a Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) project to grade separate the roadway from the rail track in SoDo at South Lander Street. Connecting 4th Avenue and 1st Avenue over the tracks is a massive undertaking, and the full budget for the project clocks in at $140 million. The federal FASTLANE grant, part of a slew of grants aimed at freight movement over both road and rail, will total $45 million. The other major source of funding and the main reason the project was brought back from dormancy since 2007 was the Move Seattle levy, which pledges $20 million.

Mayor Ed Murray’s budget proposal for 2017-2018 adds an additional $13 million to fill in the funding gap, from a source that has been getting a lot of attention lately: real estate excise tax (REET) money and funds from the sale of the Pacific Place parking garage. Both of these sources were also primary funders for the Seattle Police Department’s North Precinct project. From the Mayor’s proposed budget, after detailing the proposed 2017-2018 funding:

Nonetheless, a $27.5 million funding gap remains on this project and the City is working with partners including the Port of Seattle and Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railroad to fully fund this project.

In her press release, Senator Cantwell put a dollar figure on not building this project:

Washington state loses $9.5 million a day in economic activity because of train, truck, and urban traffic congestion–at Lander Street alone. By eliminating this congestion, we can speed up freight movement to the Ports of Seattle and Tacoma and generate significant job growth.

The Urbanist contacted Senator Cantwell’s office to determine how exactly Seattle loses the equivalent of the gross domestic product of the Maldives every year, but did not receive an answer. SDOT estimates there is currently a total of 4.5 hours throughout the average day that traffic cannot cross at Lander.

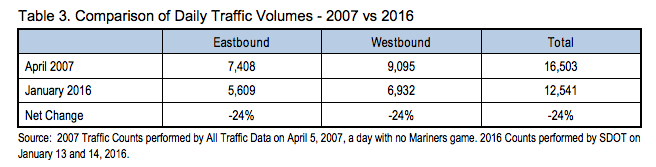

Picking up the dormant project after so many years, SDOT conducted a new traffic study in January of this year, after the Move Seattle levy was passed. It showed a 24% decrease in both directions of travel from 2007 levels.

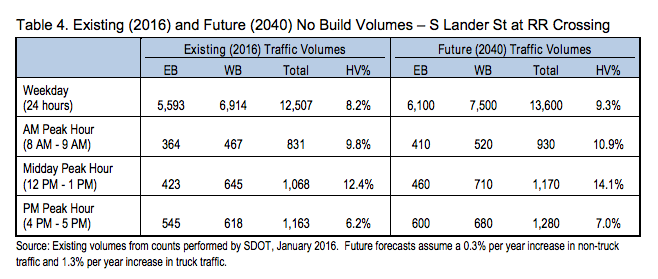

There are a number of factors that likely contributed to that decrease, not least of which is probably the opening of a light rail station at 5th Ave S and S Lander St. By 2040, SDOT does not estimate that traffic levels will get back up to 2007 levels, but they do estimate an increase of 0.1% per year, and with freight vehicle volumes increasing faster than that to become a greater percentage of vehicle traffic.

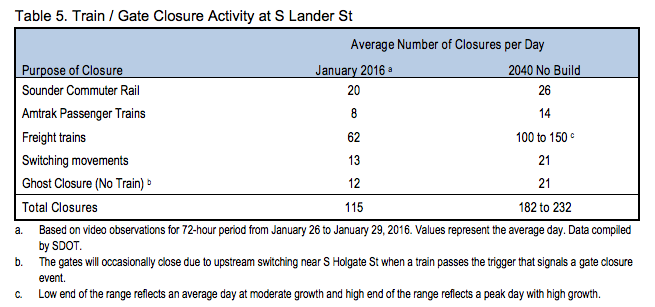

But Lander is about the future. And train traffic is expected to go up in the next few decades. In the worst case scenario, train traffic would increase by just over 100%, from 115 trains to 232 per day.

Side note: notice the “ghost closure (no train)” data point. Currently the train gates close 12 times per day when there is not actually a train, and that number is expected to increase to over 20 times per day in 2040. Of course, if we are spending $140 million on the bridge, we don’t need to worry about that happening any longer, so why worry about fixing it?

Anyway, back to traffic volume levels. Increased train traffic, not increased vehicle traffic, is the main source of delay in 2040, and the main driver to build this bridge now. Currently, the biggest delay is to westbound traffic during the PM peak. Average travel time delay for vehicles is close to 4.5 minutes. By 2040 that is expected to go up 181% to close to 12.5 minutes. Of course, that is assuming that freight traffic increases at the extreme rate that the traffic model suggests that it will. But with travel delays anywhere close to that, one begins to wonder if drivers would not work to avoid that route and find alternatives.

Even with the funding gap still outstanding, the City is moving forward with the project, with a final design expected to be completed by June of next year, with construction slated to begin the year after. With the train moving this fast, the best that advocates could hope for at this point might be to improve the pedestrian and bicycle amenities associated with the project.

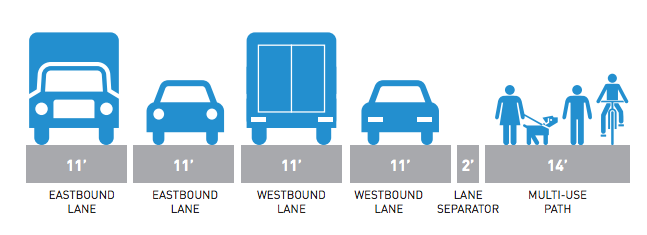

A big change in the design from the 2007 concept is that the bridge stays in the width of the existing roadway. Previous designs proposed buying adjacent real estate to expand the bridge width, which would likely have resulted in even more highway-like designs. But that limits the size of the roadway. With the two lanes in each direction, the choices for non-motorized traffic were two seven-foot sidewalks on either side, or one 14-foot multi-use path. Since the multi-use path is the only way anyone with a bike is going to be able to use the bridge, this option has been favored and now appears to be the one that is moving forward.

Grade-separating the bridge would be a considerable Vision Zero win. SDOT data pegs the number of crossing violations at the current train crossing at 494 per day, the vast majority of them pedestrians. In the past 5 years, 3 people have been killed at this crossing. But do we have the design right?

Jessica Murphy, the SDOT project manager on Lander, in a presentation to the Seattle Bicycle Advisory Board, responded to the fact that the lower traffic volumes that SDOT observed do not immediately appear to require two lanes in either direction by saying that the amount of traffic turning left and right from Lander is the main driver for the two lanes. SDOT believes that without two lanes there will not be anywhere for turning traffic to go.

With the multi-use path likely the best option, ensuring good connections for people walking and people on bikes is going to be imperative. Currently, SDOT does not appear to view the project as a high priority for bike users, with the main reason that it does not appear on the Bike Master Plan as a priority corridor. With the construction of a new connection where there once was not one, immediately adjacent to a light rail station, we should expect the corridor to turn into a major bike and pedestrian route. Induced demand does not apply simply to vehicles.

In short, the time to comment on this project is now.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.