We’ve been arguing for taller development outside of Downtown for a while; unfortunately, the City has added no high-rise zones in preliminary Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) maps released so far, except in the earlier draft University District rezone map. It’s also added no mid-rise zones generous enough to actually draw out projects despite specific advice from the Housing Affordability and Livability Agenda (HALA) Advisory Committee to do so. There’s still have time to change that and the City should do so. The reason is simple. Building tall–contrary to what the City seems to be suggesting–actually decreases displacement and maximizes affordability. The City would be incredibly shortsighted and counterproductive to rely mainly on low-rise near key transit nodes in the name of displacement.

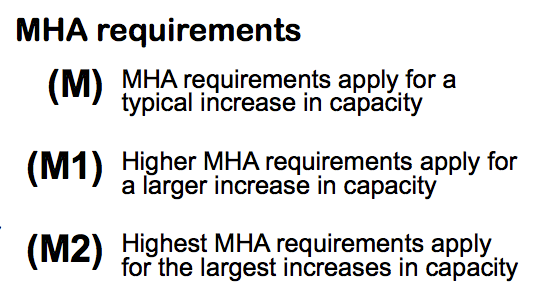

High-rise towers consume less land to produce the same amount of units. This decreases displacement because older housing stock will be consumed less quickly since each project will come with a bigger payoff and importantly with affordable units at a higher percentage or larger fee. The City has opted to step the affordability requirement up by how much it increases zoned capacity. “M” indicates a minimal increase and will have a lower requirement, but we can opt for big increases (apparently “M1” or “M2” in City parlance) and get bigger affordability requirements. “M2” generates the highest MHA requirements via the largest capacity increases. Higher capacity and higher affordability requirements are a win-win. We should absolutely pick the “M2” type zoning everywhere that is feasible.

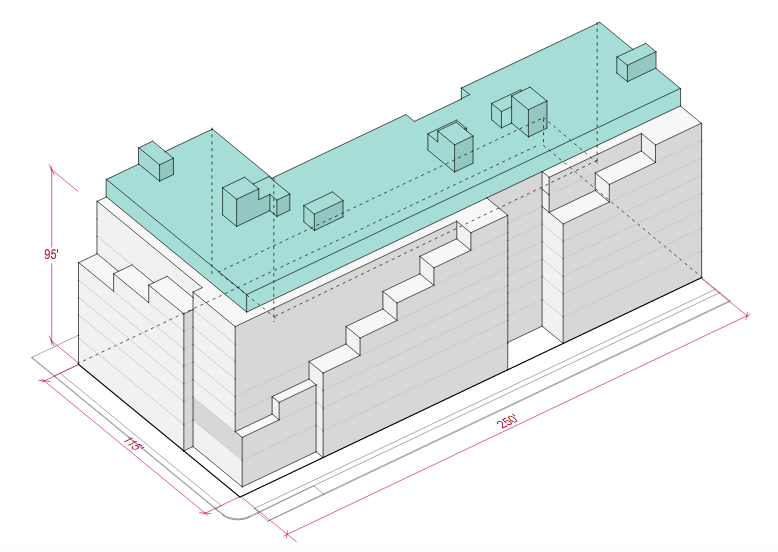

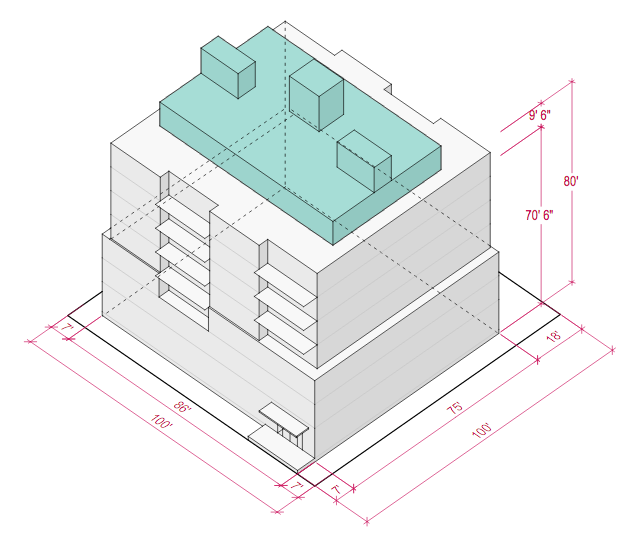

Beyond creating more affordable units and displacing fewer homes, the option of high-rises in a neighborhood improves design and unlocks more architectural options to maximize our precious station areas. It allows an architect to implement setbacks and other architectural flourishes without cutting too deeply into the project’s bottom line.

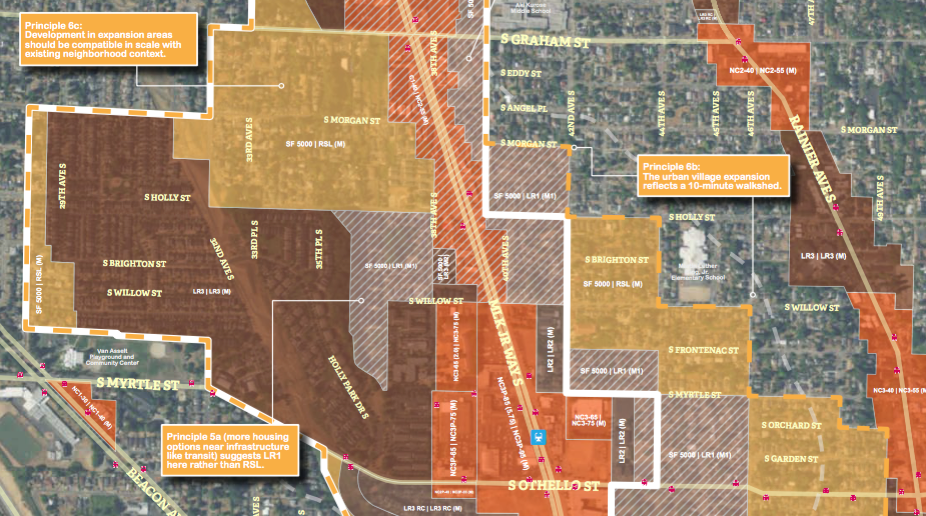

Enter Othello

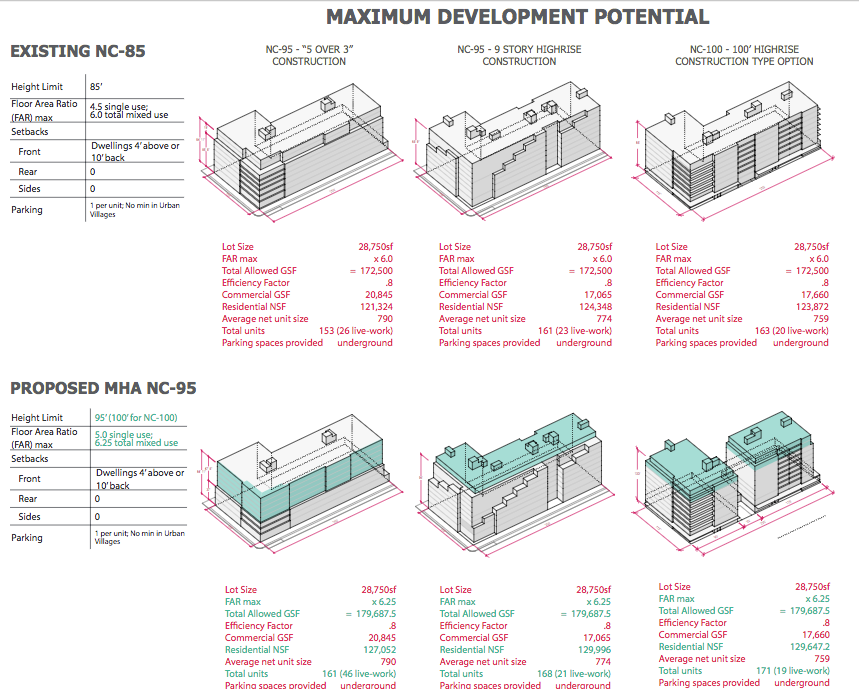

Take Othello for example. Its zoning tops out at 95 feet with NC3P-95 zoning. 95-foot height limits are effectively in the rarely built grey area between Type V (aka five-over-one) construction and Type I concrete construction. These tentative changes are in a neighborhood that has had a light rail station for a decade! It’s far time we got serious about transit-oriented development.

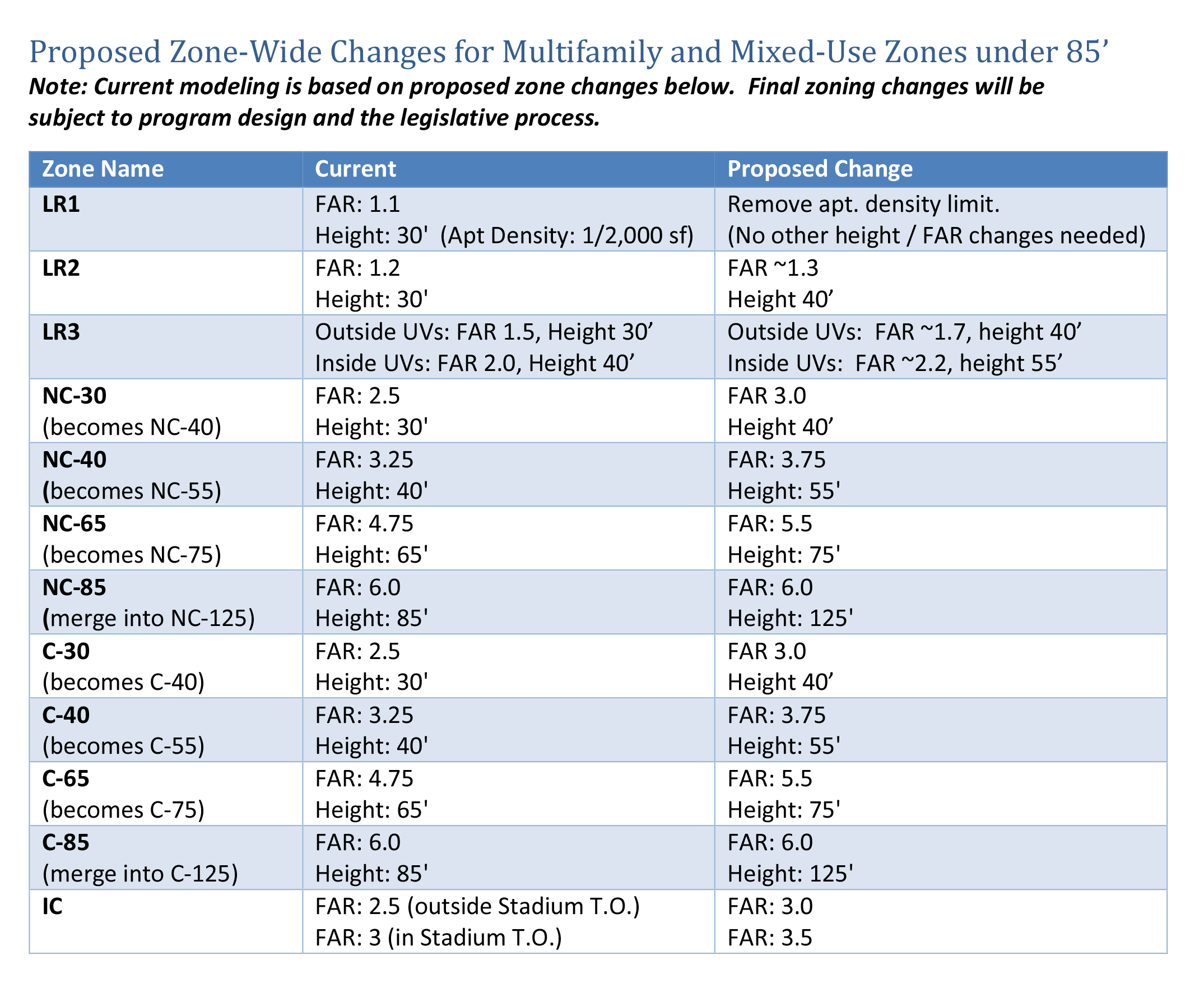

Conventional wisdom is concrete construction starts penciling out at around 12 stories which would require at least 120 feet of buildable height. This is likely why in Appendix F in the HALA recommendations suggested zone-wide changes from NC-85 to NC-125; 125-foot zones would make concrete construction feasible. It seems the City is unwisely backing away from that HALA suggestion.

If we build 12- and 15-story towers instead of more of the ubiquitous seven-story blocks, we will be building more units per block, both market rate and rent-restricted via MHA-R. We have to tear down fewer buildings and maximize our empty lots when we build tall and dense. So rather than invent a new plus-10-foot zoning type that is not likely to get built to capacity, following the HALA recommendation to upgrade NC-85 to NC-125 would be much more useful. We could even dust off the little used NC-160 zoning already in the toolbox to unlock a fuller range of options.

Mass Timber?

We could maybe fill out this grey area with mass timber construction—cross-laminated timber (CLT) is one of those technologies—as a potentially carbon negative solution to fill mid-rise, which is generally between seven and 12 stories, give or take. However, this technology isn’t proven in the United States with just a few pilot projects—like this Portland project that just cleared design review—and building and fire codes have lagged in permitting their use. If the City intends to use mass timber, it needs to change that and make its intentions clear.

HALA recommendation MF.5C recommends expediting permitting and approval of CLT. Meanwhile, recommendation MF.5 alludes to the challenges of mid-rise construction above 75 feet without mass timber technology:

Modify height limits and codes to maximize economical wood frame construction Wood frame construction is among the most cost effective new buildings for housing. This economical “Type V” building type can generally be built to 75’ when five stories of wood frame construction is built on top of a two-story concrete base. Height limits in the zoning code and to some extent limitations in the building code curtail construction in this cost-effective ”sweet spot”–with a maximum number of stories that can be built safely and practically with low-cost wood framing. Fire and life safety protections require high rise structures that are 75’ tall and above to use more expensive concrete or steel framing, which adds to the per square foot cost of building.

On the other hand, MF.5A discusses getting more out of Type V construction with building code tweaks: “An 85’ height limit could also be explored in conjunction with other adjustments to the building code to allow a sixth story of wood frame construction.”

FAR Out

And this is the point when I’m supposed to mention floor area ratio (FAR), which determines how much square footage can be in a building or on a site and could provide density through another route. A lower FAR will dictate a skinnier tower, and thereby one less profitable and likely to get built. 95-foot zones with a large FAR will still mean significant density, although perhaps not a full 95 feet of height with Type V due to the challenges just mentioned. Alas, designing an elegant nine story tower with a large floor plate is a difficult thing to do in a low rise context. Critics often call these type of designs “bread loafs.” An elegant nine-story high-FAR design can be done, but it wouldn’t give architects a lot of options. So why place our urban village hopes on a blocky type of zoning?

Cap(ped) Hill

Capitol Hill/First Hall is the one map in the five just released maps where Midrise (MR) zoning is used, specifically in a swath east of Capitol Hill Station. Unfortunately, it would appear MR will be limited to 75 or 80 feet and 4.5 FAR if the U District Draft Ordinance is any guide. So, in Capitol Hill, if we don’t increase that significantly we aren’t talking about much of an upgrade since 65-foot zones with a similar and sometimes greater FAR were already common. An even larger band within five blocks of I-5 was already zoned MR and will remain so plus an extra floor to initiate MHA. First Hill already had some Highrise (HR) zoning south of Boren Avenue and similarly is expected to gain a buildable floor or two and maybe some FAR. What is proposed in the U District is much more visionary with some 320-foot zones. Capitol Hill shouldn’t be left behind. Why are we capping it so low?

Crown Hill

Crown Hill is capped even lower than Othello with NC2P-75 being the most permissive in a band north of NW 83rd St along 15th Ave NW and Holman Rd NW. Now this isn’t to be ungrateful; having upward of 20 city blocks zoned NC2P-75 is a nice boon. And perhaps the City is making a transit justification for more limited density in Crown Hill. Sound Transit 3 doesn’t plan to bring light rail to Crown Hill, although the RapidRide C would get a boost in the package and have a quick connection to Ballard station when it opens in 2035. I’d argue that good frequent transit is sufficient to allow urban villages to break out of five-over-one into something like NC3-160 that would garner real interest in concrete construction or mass timber should that technology become viable here.

Aurora-Licton Spring Ahead

Similar 75-foot story in Auora-Licton Springs Urban Village which was the first map in the packet. Now, developers probably aren’t breaking down the door to build high-rises in this neighborhood, but that could change, especially if the RapidRide E improves like it should as Metro Transit’s flagship. The transit service is there. If the neighborhood gets “discovered,” it could really take off.

Looking Ahead

But perhaps the most crucial message here is that the major urban hubs that are still to be released (October 17th is the expected date) particularly need to break out of zones that support only five-over-one construction. They need more than NC3P-95 we are seeing in Othello. Ballard and West Seattle Junction could very well be the termini of two multi-billion dollar light rail lines. We can’t squander that investment only adding a floor or two. We need to think big. Bring out the high-rise zones.

Roosevelt and Northgate will also be fascinating to see because they will have light rail in five years or less and could easily support high-rises if only we allow it. It wouldn’t have to be everywhere in the urban village. Focus them around the station area.

This is about displacement. High-rise zoning is about reducing and mitigating displacement. It takes much less land to build the same amount of housing with the help of high-rise zoning. Doing more modest increases in zoning capacity–commonly known as “upzones”–makes no sense because that displacement will still occur even if the upzone is more modest. It’s like kicking someone out of their house and then not moving in because you’re trying to be nice.

So I repeat Anton’s call to action from one year ago: “[T]he Seattle City Council will vote on the HALA policies. Let them know you support the HALA recommendations and would like to see an even more significant relaxation of restrictions on the heights of buildings with the aim to maximize future benefits from light rail investments, slow down rent increases, and increase the net amount of affordable housing.”