Block The Bunker activists celebrated after Mayor Ed Murray backed down and put the $149 million North Precinct police building on hold. But they quickly turned their sights on their next foe: a $210 million youth jail planned for the Central District. Protesters railed against the youth jail repeatedly when they took over and shut down the Seattle City Council meeting Monday.

A Shady History

King County got its coveted youth jail funded via a deceptively worded 2012 ballot amendment that failed to mention the operative words “jail” or “incarceration.” Instead it opted for a euphemism: A “Children And Family Justice Center” that “services the justice needs of children and families.” That does sound better than youth jail. The ballot earned or perhaps bamboozled 55% of the vote.

Early this year, a group called Ending Prison Industrial Complex (EPIC) filed a lawsuit seeking an injunction to halt construction, which was due to begin in 2017. Attorney Knoll Lowney, who is representing EPIC, not only argues that the ballot language was misleading, but also disputes the case that the County made painting the old facility as obsolete.

[T]he suit cites the county’s own 2011 analysis of the building, which described the building as “generally in good condition.” The analysis said repairs to the building would cost a total of $795,981—not millions of dollars, as the county has repeatedly claimed. Lowney alleged the county had “cooked the books.”

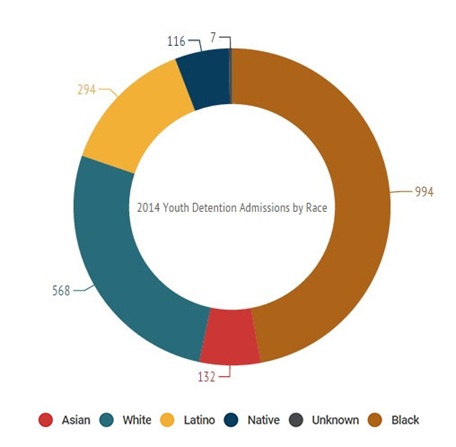

Moreover, the lawsuit argues youth incarceration disproportionately harms black youth—to a shocking degree in fact—and does not work as a diversionary tactic. Ansel Herz reports:

The lawsuit makes broader arguments against youth incarceration. “Incarcerating a youth for low-level crimes makes them more likely to reoffend than those who were not incarcerated,” the suit states. The suit points to the county’s acknowledgment that racial disparities have grown, even as the sheer size of its youth detention population has been drastically reduced. Eight percent of county youths are black, but they represent about half of those detained.

It does not appear EPIC succeeded in getting an injunction since most sources have indicated that the Master Land Use Permit the County is seeking from the City of Seattle is the last major obstacle the project needs to clear to break ground, barring another Block The Bunker stunning turnaround anyway.

Jail Or Justice Center?

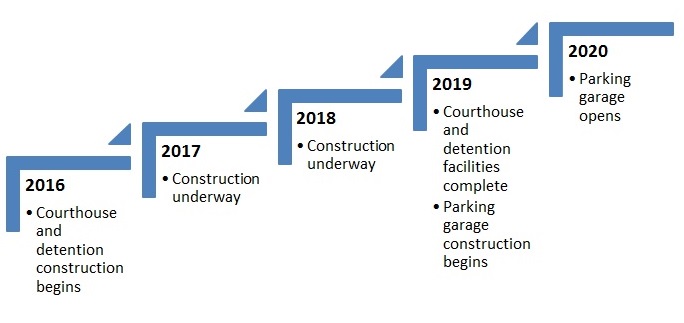

The County, for its part, argues its new facility is foremost a 137,000-square foot courthouse with ten courtrooms, an increase of three while providing a more welcoming youth jail/courthouse with a daycare center and programming space. Furthermore, King County argues the 92,000-square foot detention center moves in the right direction by reducing the number of detention beds to 112 compared to the current facility’s 212 beds: “Design allows for flexibility to reduce detention space in the future. This facility will have 100 fewer detention beds than the current one has (212), almost cutting the number of beds in half.” King County even describes the detention center as “therapeutic” in its website. Note, 40 of the beds that were cut were not done on King County’s own accord but after pressure from EPIC activists forced its hand. King County’s promotional plea for a new youth jail is below.

Detention bed reductions aside, the City’s official goal isn’t cutting in half youth incarceration but ending it entirely. The Department of Justice argued as early as 1973 that youth jails and (adult jails for that matter) create crime rather than they prevent, but that hasn’t necessarily translated into policy. The Seattle City Council did set a goal of zero youth incarceration in 2015; $210 million seems an awfully large investment to make in a practice Seattle aims to end.

The County hasn’t really addressed a major Block The Bunker question: why is updating judicial and jail facilities to the tune of $210 million a higher priority than directly serving marginalized communities by investing that money in struggling schools, boosting social services, building subsidized housing, expanding drug treatment, or enacting any number of other early interventions that prevent juvenile crimes in the first place? Now the County’s levy funds probably aren’t very fungible, but it seems likely some could be put to some better use or returned to taxpayers.

Parking Issues Again

The plan also calls for a large above ground parking ramp: “The 360-stall structure’s top floor will be at ground level on its north side and two floors above ground on its south side.” Tell me that doesn’t sound like a monstrosity. Obviously if that design went through Seattle Design Commission, Chair Shannon Loew told or would tell them that the “era of building above ground parking is over,” as he told the architects of the North Precinct last week. A parking ramp that large inevitably drives up cost (and clearly the detainees themselves are not using it). Moreover, since the parking ramp would not be operational for the first year of the center’s operation, it’s not clear it’s a necessity rather than an expensive convenience primarily for staff.

Well It’s Green At Least

Well It’s Green At Least

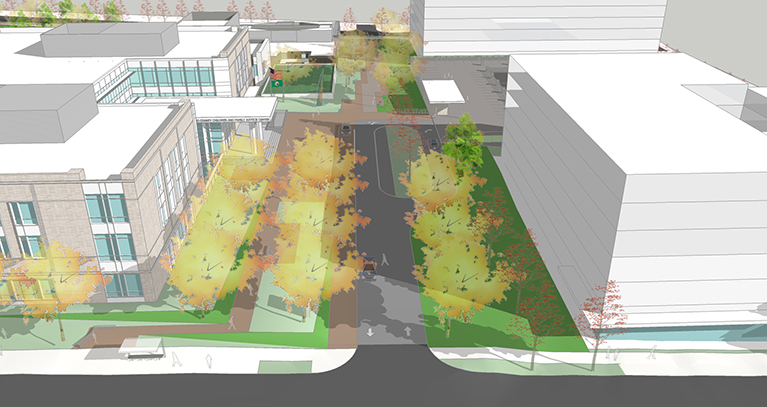

In what could be construed to be an effort at deflection, the project website focused on the projects green benefits including Gold LEED certification, a green roof, pervious pavement, bioretention gardens, and energy-efficient features that “will use 26% less energy than required by the City of Seattle’s Energy Code.” The plan also boasts of its public open space, including, “1.55 acres of the site will be open areas that include the Alder Connection, a pedestrian and bicycle pathway that will reconnect East Alder Street between 12th and 14th Avenues after a 50-year closure, space on the corner of East Remington Court and 14th Avenue, and public plaza space facing 12th Avenue.” These are good features, but do they compensate for a project that appears fundamentally wrongheaded from its inception?

Make Your Voice Heard

This is a King County project so a good place to start for addressing comments would be King County Executive Dow Constantine (kcexec@kingcounty.gov) and King County Councilmembers, particularly:

- Joe McDermott (joe.mcdermott@kingcounty.gov) who is Council Chair and represents the 8th District including Southwest Seattle, First Hill, and the youth jail site;

- Larry Gossett (larry.gossett@kingcounty.gov) whose 4th District includes Southeast Seattle and the CD;

- Jeanne Kohl-Welles (jeanne.kohl-welles@kingcounty.gov) whose 3rd District starts Downtown and extends throughout Northwest Seattle; and

- Rod Dembowski (rod.dembowski@kingcounty.gov) who represents Lake City.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.