The face of Ballard has experienced remarkable change over the past decade with renewed interest in major developments like the Ballard Hotel, AMLI Mark 24, Urbana Apartments, and Odin Apartments. In 2014, the Office of Planning and Community Development (OPCD) kicked off a process to determine neighborhood priorities for a comprehensive update and realignment of urban design objectives in the neighborhood core. That process culminated in January with specific recommendations to address streetscape improvements, open space, transportation, and urban design issues. Since May, the City Council has been chewing on a subset of those issues that would implement targeted zoning and development standards changes.

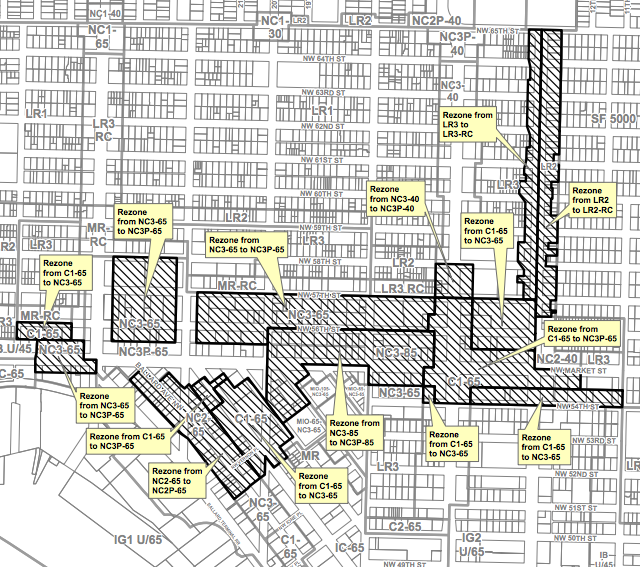

Proposed Rezones

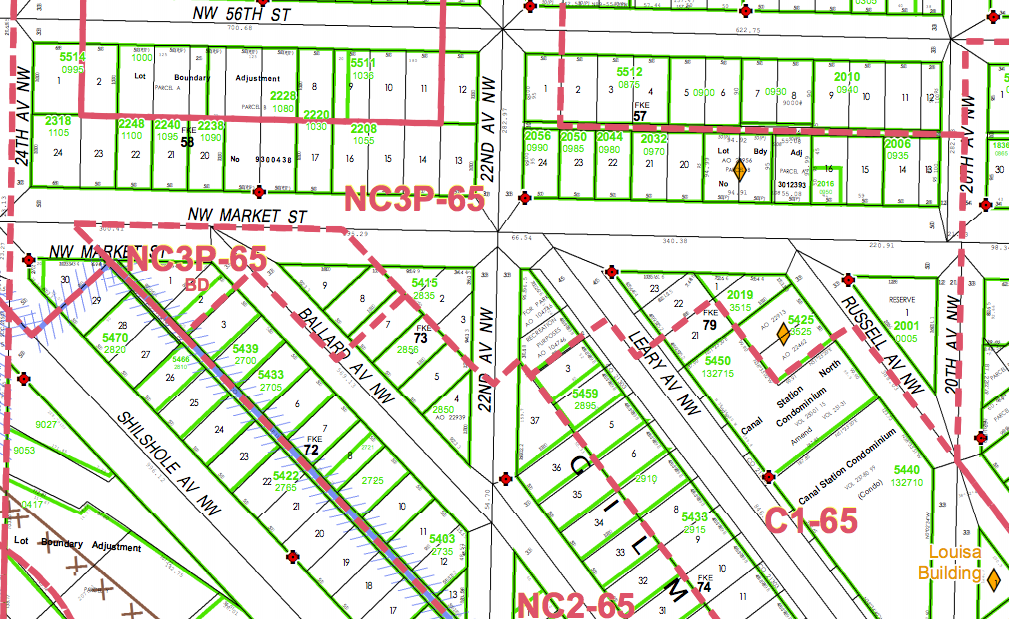

In keeping with the spate of recent rezones, the proposed changes would be density neutral meaning that development capacity resulting from the zoning changes likely won’t change much if at all. Area-wide rezones under the Mayor’s Housing Affordability and Livability Agenda, however, could increase development capacity down the road. In the meantime, this rezone is focused on three primary changes:

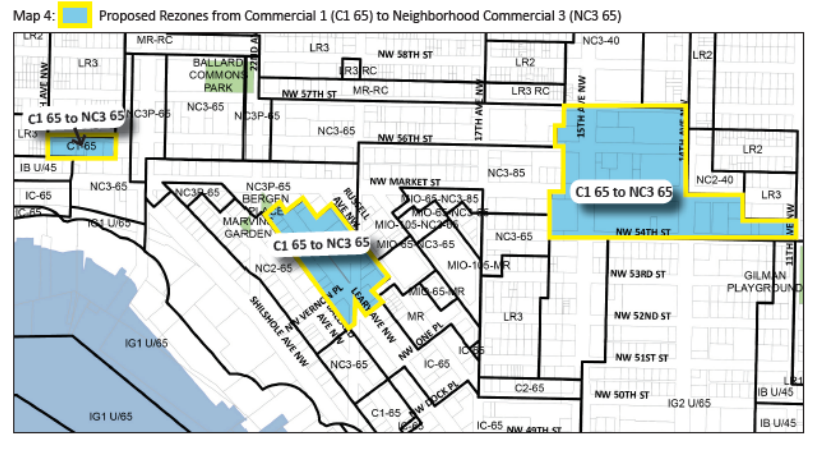

- Rezoning properties zoned Commercial 1 (C1) to Neighborhood Commercial 3 (NC3);

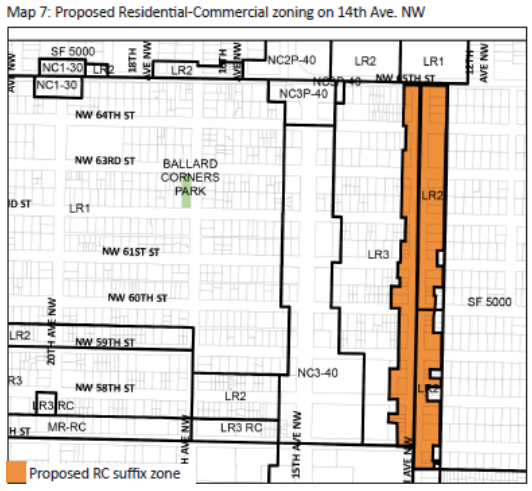

- Rezoning select Lowrise 2 (LR2) and Lowrise 3 (LR3) properties to include a Residential Commercial (RC) suffix; and

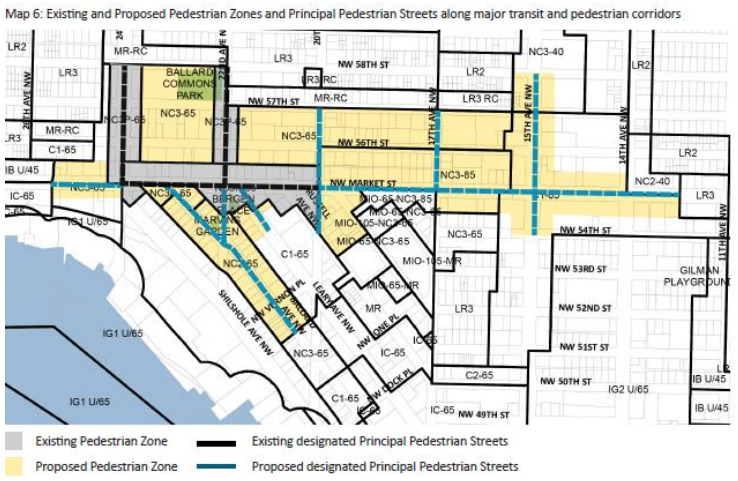

- Rezoning most Neighborhood Commercial 2 (NC2) and NC3 properties–whether already zoned as such or proposed to be–to include a Pedestrian (P) suffix.

The overall rezone is essentially built around the idea of creating a more walkable, active, and attractive neighboorhood core as opposed to shooting for higher densities. Although, one segment of the rezone spills north of NW 58th St.

So let’s look at what the rezones are.

Much of the C1 zones in the central core will go away in favor of NC3 zones. C1 zones are flexible zones allowing both commercial and residential uses. However, the zoning regulations tend to allow larger auto-oriented commercial uses than their NC zoning counterparts. It’s not uncommon to find standalone uses like car lots and big box retailers in C1 zones. NC zones, however, typically have development standards that encourage a mixing of pedestrian-oriented retail and residential uses closer to the street. The primary difference between NC1, NC2, and NC3 zoning is the variety and size of non-residential uses (e.g., retail, offices, manufacturing, and utilities) allowed. For instance, NC2 is more limited than NC3 in that regard, but allows the same amount of FAR (i.e., density) as NC3 zones, so long as the maximum height limits are the same; that same is true for NC1 compared to NC2 or NC3. Most of the Ballard rezones to NC3 will be from pockets of C1 on NW 56th St, NW Market Street, NW 54th St, and Leary Ave NW.

The RC suffix allows limited commercial activity on residentially-zoned properties wherever it is designated. In the case of Ballard, the RC suffix would permit up to 4,000 square feet of street level uses on properties where it is designated. The idea behind the zoning suffix is to give some flexibility for small-scale commercial services that would support daily needs of local residents. The suffix, as proposed, would be added to all properties zoned LR2 and LR3 facing 14th Ave NW, from NW 56th St to NW 65th St–which is why the zoning line is comparably jagged to other areas proposed for rezones.

The P designation not only encourages streets to be walkable and active shopping districts, it explicitly requires the types of characteristics to realize them. The P designation comes with a variety of development regulations:

- It sets minimum FAR requirements for new developments to achieve, which in turn encourages denser developments of individual sites;

- It sets a minimum requirement for 80% of street level uses facing a Principal Pedestrian Street to have active businesses, meaning that there is a mixing of restaurants, shops, and services while also prohibiting certain uses like gas stations;

- It requires 60% of street-facing building facades on Principal Pedestrian Streets to be transparent;

- It requires features to enhance walkability like requirements for overhead weather protection (e.g., awnings and canopies) and wider sidewalks; and

- It places specific restrictions on parking, which establish maximum parking amounts and force parking areas away from active street fronts.

The P designation directly correlates to streets that are designated as Principal Pedestrian Streets. City planners have been slowly designating more and more streets as Principal Pedestrian Streets since 2015. Ballard was excluded from a larger citywide update in 2015 because it was determined that waiting for the Ballard subarea plan update was the more appropriate way to evaluate designations.

Proposed Design Standards

Neighborhood-specific design standards are also baked into the proposal, which include maximum facade widths and lot coverage as well as street-level and upper-level setback requirements. The proposed development standards would only apply on properties zoned NC within the Ballard Hub Urban Village. The goal behind the design standards is to encourage new development to respond the historic nature of Old Ballard and the pedestrian realm in the bulk, scale, and feel of building forms.

For instance, properties in Old Ballard came in lot width multiples of 50 feet when they were originally platted. This led to buildings to range from half that size to double depending upon how property owners chose to use their lots. Old Ballard also presents a unique grid pattern with blocks running diagonally northwest-southeast and generally long blocks regardless of orientation. The longest blocks (east-west) are up to 770 feet wide with most well above 550 feet in width. Yet, the average block length in Downtown Seattle is 250 feet. Developments that occur on large sites (10 or more average Old Ballard lots) tend to fail at responding well to the historic and pedestrian-oriented nature of the area, which is why OPCD has recommended a menu of development standards changes:

- Maximum structure width. To retain the scale of traditional blocks, a new requirement would set the maximum structure width at 250 feet. The result of this should be fewer mega-structures appearing on blocks and instead encourage developers to break up developments.

- Maximum lot coverage. While the rest of the design standards apply generally with the urban village, the maximum lot coverage requirement would only apply to to sites that are 40,000 square feet or larger in size. Development proposals that hit this threshold would be subject to an 80% maximum lot coverage for buildings. The remaining 20% of area on such sites would be encouraged to include things like landscaping and open space, art installations, sidewalk cafés, mid-block connections, and other outdoor amenities.

- Facade modulation. To retain visual interest closer to the street level, new buildings would be required to modulate the lower portions of their facades. This requirement would be applicable to the lower 45 feet of a building and mean modulating the facade at least once every 100 feet in facade width. The minimum modulation standard would be a 10-foot stepback of the facade from the street that is a least 15 feet wide before bringing the facade back toward the street.

- Street-level setbacks. A very select stretch of 15 Ave NW–Ballard’s main north-south thoroughfare–on and near NW Market St would be subject to special street-level setback requirements. The street-level setbacks would only apply from first 6 to 10 feet from the edge of the sidewalk where designated and require 10 feet of the vertical space above the sidewalk grade to remain clear of any structure. Presumably, it would be possible to cantilever a building over portions of this setback area. Given the fact that the street is so busy, OPCD believes that it would be valuable to give pedestrians, transit users, and even sidewalk diners more room to use and enjoy the space safely and comfortably.

- Upper-level setbacks. Upper-level setbacks will be required on any portion of a building above 45 feet in height that abuts a street. Two types of upper-level setbacks may apply to a building. An average setback of 10 feet from the adjacent street would be required above 45 feet and up to 65 feet in height. Portions of a building above 65 feet would have to achieve an average setback depth of 15 feet from the adjacent street. The result of this should be buildings that allow more light and air to filter down to the street level and reduce the feel of building bulkiness to the pedestrian’s eye.

Certain requirements discussed above could be waived or modified for new development proposals. Only proposals on sites that are greater than or equal to 40,000 square feet could qualify for special code departures through the design review process. New developments that qualify would have two choices in alternative amenities to provide on-site: usable open space that interacts directly with the street; or a woonerf, through-block pedestrian connection, amenity space, or combination thereof that also acts as separation between structures.

Proposals for usable open space would have to be designed so that they are at least 20 feet in depth from the sidewalk and run along 30% of a building’s street-facing facade. The open space would also be be accessible meaning that it couldn’t be more than four feet above or below an adjacent sidewalk. The impetus for this is to encourage more publicly-oriented open space in an area that lacks those kinds of neighborhood amenities.

Proposals for woonerf, amenity space, through-block pedestrian connections would have to provide ample space for users. The proposed standard would be a minimum width of 20 feet and generally consistent with the grades of adjacent sidewalks. Any such space would have to be design in north-south manner in order to qualify. The goal here is to encourage more pedestrian permeability through the neighborhood, especially on long blocks that effectively act as serious barriers to walking.

What the proposal does not tackle is the minutia of project-level aesthetics, which understandably is an area of deep personal contention for many and very subjective. Rather, the focus of the overall rezone and development standard changes is to address higher level design aspects that affect the pedestrian realm and historic context of Ballard. The sum of the OPCD proposals should greatly improve the quality of developments that are taking shape in Ballard.

The Planning, Land Use, and Zoning Committee will convene today to consider a vote on the recommendations, and if passed, the legislation could appear before the full Council after the two-week recess beginning on Monday.

UPDATE (9/6/2016): The Ballard rezone passed on September 6, 2016.

Stephen is a professional urban planner in Puget Sound with a passion for sustainable, livable, and diverse cities. He is especially interested in how policies, regulations, and programs can promote positive outcomes for communities. With stints in great cities like Bellingham and Cork, Stephen currently lives in Seattle. He primarily covers land use and transportation issues and has been with The Urbanist since 2014.