When I was four years old, I wrote a letter to Mother Nature. Signed, sealed, and delivered to the boulder in our suburban front yard, I mourned the new developments tearing down forest and farmland and asked her to intervene. I grew up playing in the woods behind our home, watching birds come to our feeder and deer eat from our cherry tree. I built forts and rode my bike through the woodland trails. Watching bulldozers tear down trees spurred one of my first memories of injustice. More trees came down, and I realized Mother Nature needed help.

When I was five years old, my family went to the airport. We rode the tram between terminals and I fell in love—not with a person, but with the tram. The way it whisked us away, gliding effortlessly along its tracks, an electric whirring below. I ran to the front window and wondered why they put an amusement park ride in the airport. This was so much better than a car ride.

When I was 12, I was looking for fun with my friends. Too young to drive, all we had were strip malls within walking distance. When we walked, it was often down dead sidewalks along busy roads. Not allowed to sit long in the parking lot for threat of “loitering,” we didn’t have many places to go. The QFC eating area was a bright spot, and even they didn’t like us there long. We craved activity, stimulation, energy. We wanted something to do. We could tell this place wasn’t designed for us.

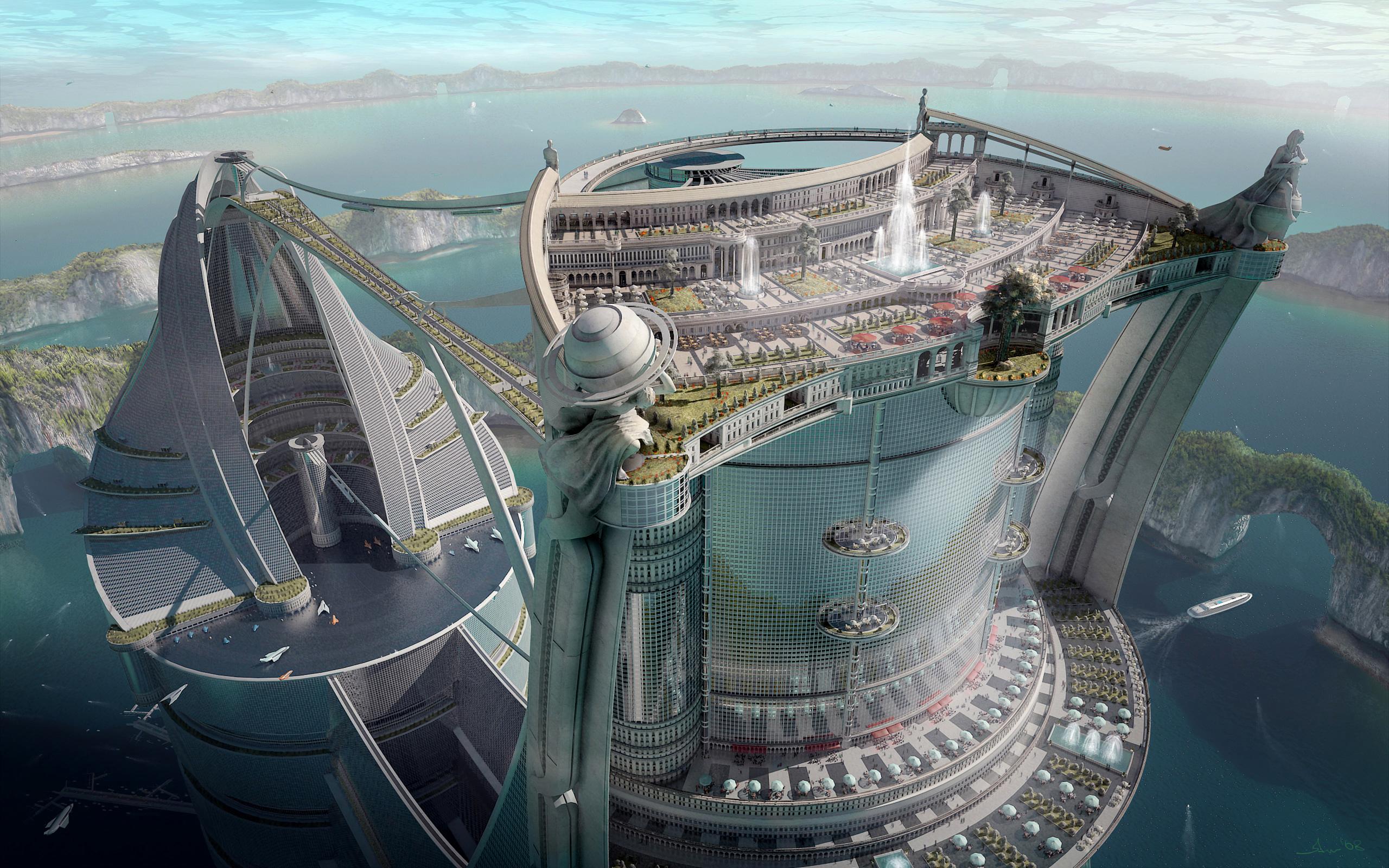

When I was 13, I took a science fiction class. Yes, my middle school offered a science fiction class. We learned about a futurist who drew cities self-contained in enormous super-structures. These structures preserved the natural habitat around them, allowing nature to live largely interrupted in its space, while humans lived in ours. Separate, but just minutes away. These cities could be placed anywhere—amongst the trees, along the coast, floating in the ocean. It looked like living in an amusement park, or the space station in Zenon, Girl of the 21st Century (zoom, zoom, zoom, anyone?).

When I was 14, I was home for summer and bored. I hopped on a bus (the 554) and went into the City, soaking in the scenery from the window seat. My destination was wherever the last stop would take me. I wanted to watch the world go by. There was life in the City.

When I was 15, I came out to my friends and family. Feeling virtually alone in a school of 1,500, I sought community—people who could understand me. That community was in the City across two lakes, but visible from our hilltop. The Columbia Center was my beacon. There I’d find people like me, safe places, dances, resources, friends, dates, role models, Pride celebrations. I could escape the silent judgment and experience, for the first time, affirmation.

When I was 18, I started reading the Seattle Transit Blog for updates on the new First Hill Streetcar. I kept checking back, and began to read articles about other topics, like stop spacing, signal prioritization, and bus bulbs. I also learned that housing density and land use are what make public transit successful. It explained why my neighborhood DART route was almost empty, and the buses downtown were packed. It could even support more rail. I wanted more rail and fewer empty circulators.

When I was 22, I graduated from college at Western Washington University. I needed a job. I needed my friends. I needed a place to live. I moved to Seattle because it had all of these things—more of them than any place else—and more. It had Cal Anderson Park and Cupcake Royale (the best cupcakes in town—I’ll fight you about it). It had the monorail and streetcar that brought me back to my days of riding the airport tram (I still ride it, even when I don’t need to). It even had a train to take me directly to the tram at the airport. Seattle was the land of opportunity. It still is.

When I was 23, I found The Urbanist, a group of people dedicated to creating more of what makes cities so great. More homes for me and my friends—most of whom have moved to the City in the last five years. More transit for entertainment and a car-free lifestyle. More density to slow sprawling development and protect forest and farmland. More safe places for my queer community to flourish. More vibrant and walkable neighborhoods with things to do, places to go, and delicious desserts to munch on.

I’m an urbanist because my life brought me here. There’s no one issue that defines my urbanism: not housing, not the environment, not transit, not economics, not queer issues. I’m an urbanist because my entire experience about what makes a good life points me to the City.

Ben Crowther

Ben is a Seattle area native, living with his husband downtown since 2013. He started in queer grassroots organizing in 2009 and quickly developed a love for all things political and wonky. When he’s not reading news articles, he can be found excitedly pointing out new buses or prime plots for redevelopment to his uninterested friends who really just want to get to dinner. Ben served as The Urbanist's Policy and Legislative Affairs Director from 2015 to 2018 and primarily writes about political issues.