In December 2015, a team of private security guards from Central Protection began making six-hour patrols around the Magnolia residential area. In February 2016, Joe Villarino, director of the neighborhood association that hired them, posted their first results online. Comparing Magnolia crime data from that last December to crime in December 2014, Villarino pointed out “a 7% decrease in property crimes,” as well as in crimes “across the board.” The patrol, he meant to say, was doing its job.

Magnolia is one of a number of Seattle neighborhoods—also including Laurelhurst, Windermere, and Whittier Heights—that have hired security teams in recent years to deter and respond to property crime. The logic of the neighborhood groups is simple: If property crime is rising throughout Seattle and law enforcement cannot keep pace, hiring extra security is a sensible, if expensive, recourse.

But is it working?

It depends on whom you ask. Brad Renton, director of the Whittier Heights Patrol Association since its inception in 2014, says crime in his area has fallen. “‘People will come up and say, ‘Hey, I left my laptop in my car overnight and it was fine—two years ago it would have been gone in the morning,’” he says. But locating data to support those conclusions is tricky. Renton says he gets his numbers by asking the Seattle Police Department how many calls have come in from his neighborhood.

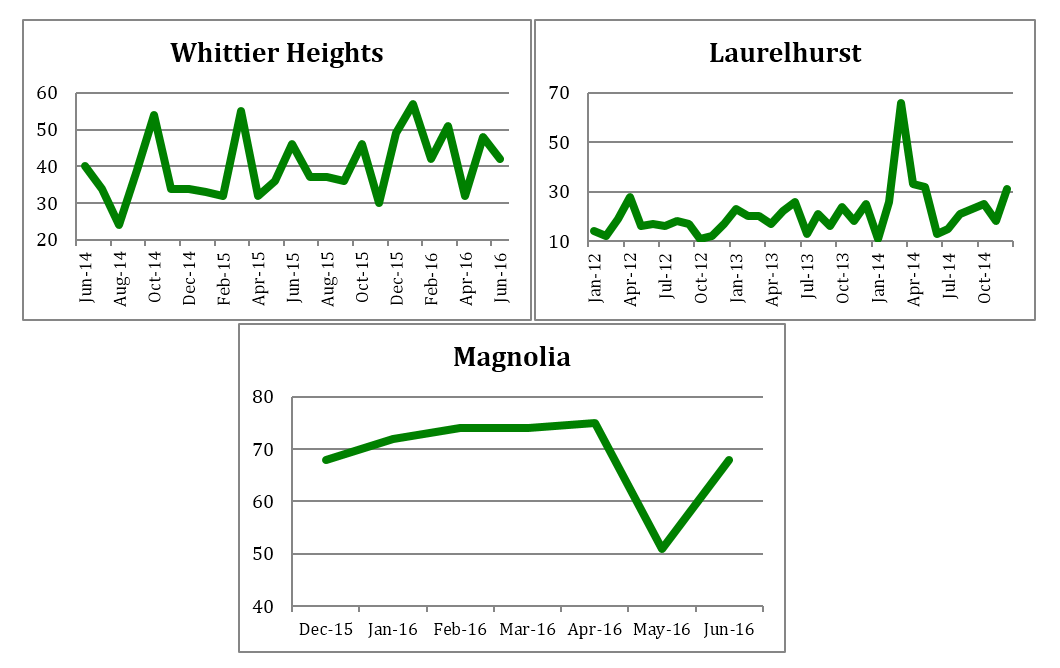

The police station could not provide such data on request, and pointed instead to the online Neighborhood Map that tracks Seattle police reports. But when data on the map for Magnolia, Whittier Heights, and Laurelhurst are analyzed over critical time periods, no decline in crime is apparent.

The only clear takeaway from this data is that crime is highly variable and numbers easy to misinterpret. A difference of, say, 7% between two months is actually insignificant.

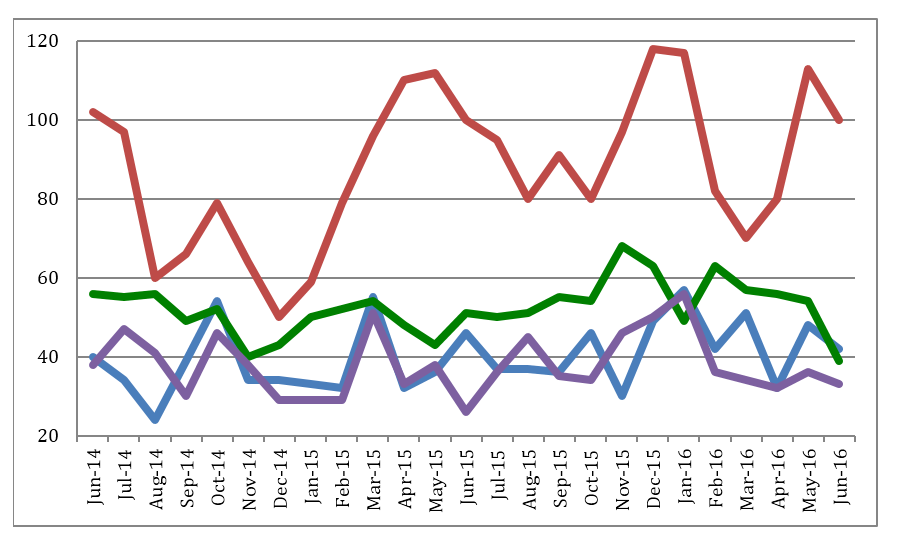

Of course, containing criminal activity at existing levels, or mitigating its rise, could be seen as a success when crime is rising in general. But there’s no evidence that the increase in crime in these neighborhoods is any slower than in neighborhoods nearby. Here’s Ballard as an example:

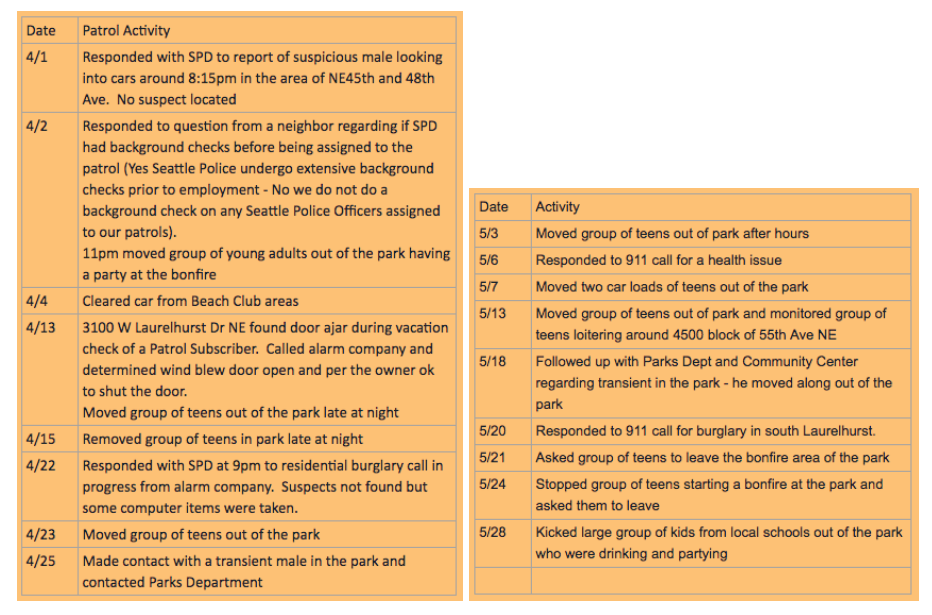

So if the data don’t reveal a decrease in crime, why do residents feel safer? The Laurelhurst Blog, which has published reports of its patrol’s activity, suggests an answer. Two reports from the blog show security mostly kicking the young and the homeless out of public parks after hours. Renton, too, attests that his officers have confronted homeless drug users, saying their policy, rather than making arrests, is to confiscate any drugs and induce the parties in question to “move along.”

All this suggests a cautious conclusion about extra neighborhood security: it probably doesn’t push crime out, but it does push people out.

Under the banner of hired security, there are real differences between privately-trained guards (the kind Villarino’s patrol hires) and off-duty SPD officers (the kind Renton’s hires). Private guards are limited, legally, in how they can respond to an incident: They can’t make formal arrests, tow cars from public spaces, or anything else a private citizen can’t do.

Off-duty law enforcement are limited in where and when they can respond: They can’t search property or stop people without probable cause, and they are duty-bound to protect everyone in the neighborhood. But their police status means they can respond to 911 calls, reducing the delay that upsets so many Seattleites.

But no matter whom neighborhoods choose to hire, crime patrols, by nature, often focus most of their attention on monitoring “suspicious” individuals. And officers need to be careful “not to do anything to target,” says Sergeant Paul Gracy, who has been at SPD for 36 years and heads the West Precinct’s Community Police Teams. The CPT often handle conflicts between permanent and transient neighbors, and make it a policy to reach out with conversation and offers of social services before pursuing other action. Hired officers “should be out there to protect,” Gracy warns. “You can’t hire your own police department to pick on people.”

The other option for neighborhoods is to register a watch group, a practice Gracy says is becoming more common. Interestingly, it might also be what security companies would prefer.

Kim Legaspi of Seattle Security Inc., a company chaired by prominent members of the Seattle Police Officers’ Guild, says they have struggled to find officers who want consistent neighborhood assignments or have time to take them. Legaspi believes that neighborhood watch groups are a better choice for taking care of “unwanteds” in a community. She says her own watch group saw a suspiciously parked car and was able to call the police to have it removed.

Private security might have handled the incident differently. In March, a Central Protection officer on Magnolia’s neighborhood patrol encountered a local resident sleeping in his car. Their interaction led to the officer pepper-spraying the man, pinning him against his car and destroying his phone, resulting in a lawsuit against the company.

Negative interactions like these, Renton says, contributed to his choice to hire off-duty SPD officers, who in his view have superior training.

But Legaspi thinks it would be “crazy” if every Seattle neighborhood hired off-duty police. “The officers wouldn’t get any sleep. They’re already paid to be everywhere at once, so why can’t we help them out?” she protests.

More than anything, these disagreements raise the question of what, exactly, neighborhood security guards are being hired to do. If their function is to reduce crime, it doesn’t appear to be working. But if their main function is to respond to 911 calls, then the increased monitoring of locals, particularly the homeless, is a lamentable side effect. One wonders whether different solutions could bypass this problem, or even serve to connect residents on the street to more social services. Sergeant Gracy, for one, says he could always use more staff.

Wanda Bertram is a Seattle-area freelance writer focused on policing, incarceration, and inequality.