The new 520 bridge is now open to cars, but the Seattle side of the project is still a long way from completion. Pedestrians and cyclists have another year to be able to use the bridge to get between Seattle and the Eastside as the pedestrian bridge only extends as far as the floating bridge portion, which doesn’t fully connect to Seattle.

One big aspect left to be started is the “Montlake lid”, a cap on a segment of the freeway at the 520 interchange with Montlake Boulevard. This project has a great deal of potential, providing added green space where there might have otherwise been open freeway.

Montlake: Seattle’s Other Freeway Lid

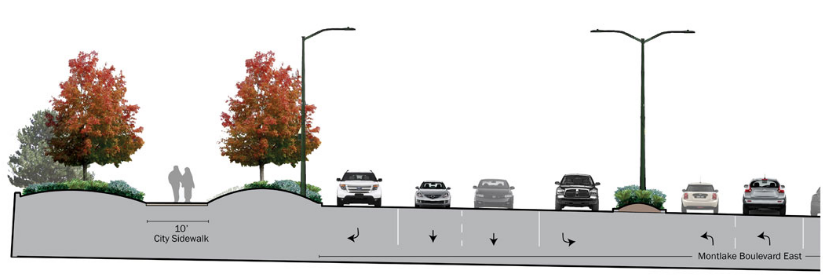

Recently, the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) has released a series of concept illustrations for the entire west side corridor, including the new design for the newly remade Montlake Boulevard. Its cross-section schematics of the street are too large to include all of it at the same time, which is the first big red flag.

Yes, that’s five lanes in the northbound direction. And the southbound direction has four lanes.

So that’s an increase of three total lanes over the freeway. But that’s not even the worst part.

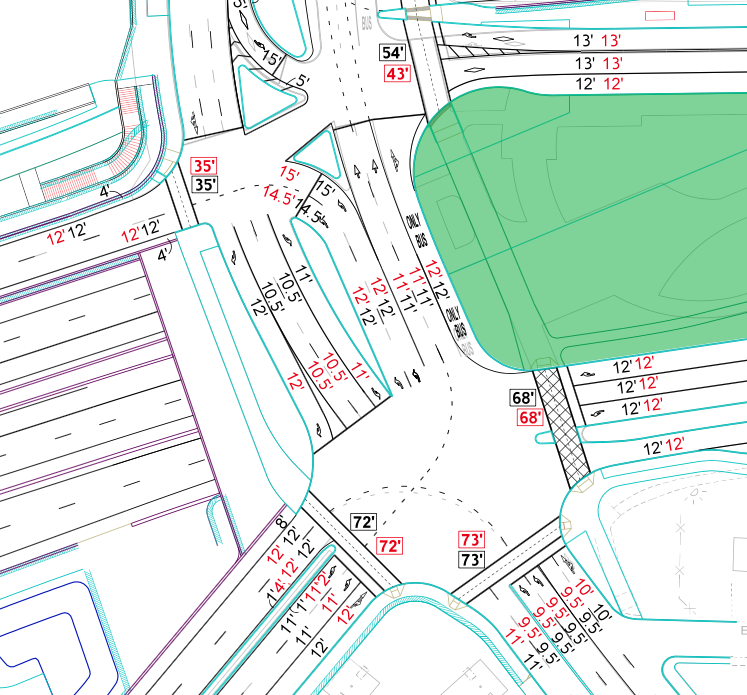

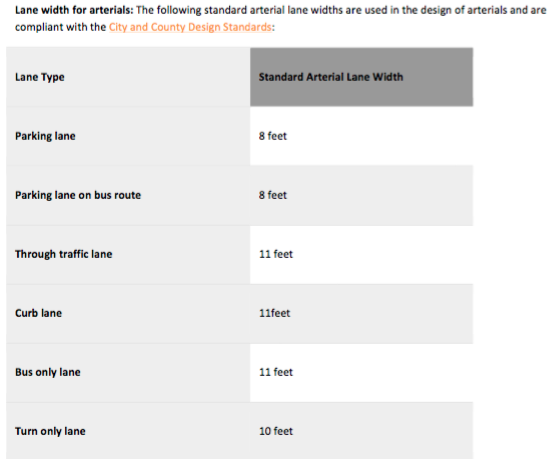

WSDOT’s drawings that were released to the public do not include the widths on any of the lanes, but if you are thinking they look pretty big, then you’re correct on that as well. We were able to obtain an internal document that shows the widths of the lanes, and that’s the truly terrifying part. Note that this is a city street, not directly part of the freeway project.

Contrasted with the current configuration:

The City of Seattle’s draft right-of-way improvement manual has no place where lanes wider than 11 feet are necessary. The twelve and even thirteen feet lanes here are literally off the charts—highway designs on city streets. Wider lanes encourages higher speeds when exiting the freeway.

Montlake Boulevard is also not considered a major freight route on Seattle’s update to the Freight Master Plan, currently under review, so wide lanes built to handle high volumes of truck traffic are not necessary here, at least from the City’s perspective. So the big question is whether they will stand up for the new standards that they have determined are best for the city’s streets.

Another major question still outstanding is the issue of bus priority. The blueprints show bus-only lanes through the interchange, but the cutout drawings show buses in HOV lanes—on city streets. This is going to be the biggest chokepoint in the “high capacity corridor” being studied for upgrades to the current Route 48.

WSDOT will also be collaborating with the City of Seattle on the I-5 interchange at Roanoke Street, another instance where it will be very important to ensure that Seattle design requirements are followed and not WSDOT highway standards. There are signs, however, that things might be starting to change at the State’s department of transportation. They recently introduced a concept called practical design, which appears to favor multimodal corridors over traditional state highway projects from purely a cost-savings standpoint. Perhaps folks at WSDOT are realizing they may need to come to grips with their massive maintenance backlog and stop running headlong into new projects without considering their long-term plan for sustainability.

In the meantime, we should send them the message that Seattle doesn’t need highway-level street designs on our arterials.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.