Councilmember Mike O’Brien’s legislation that seeks to encourage more backyard cottages and mother-in-law apartments hit a snag last week, as the Queen Anne Community Council filed an appeal with the City’s hearing examiner that will delay the legislation for at least three to six months.

With its talk of a “full assault upon our single-family neighborhoods,” the community council’s opposition to this legislation (as well as related proposals to diversify the types of housing in single-family zones as part of the city’s Housing Affordability and Livability Agenda) paints a picture of radical changes to the density and character of Queen Anne, turning quiet residential streets into dense, traffic-choked thoroughfares.

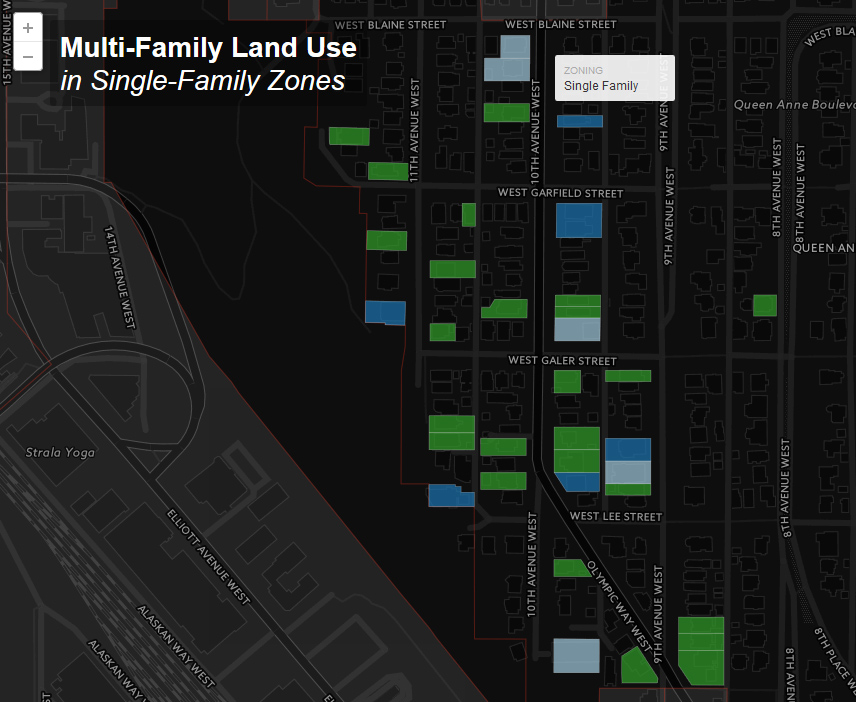

Luckily, we don’t need to imagine what Queen Anne and other neighborhoods would feel like with more of this type of housing—we’re blessed with living examples all around us. Jeffrey Linn’s excellent work mapping all of the multi-family housing (including duplexes and triplexes) in the city’s single-family zones shows how much of the city is already living the community council’s nightmare and enjoying themselves just fine, thank you.

As a resident of one of these neighborhoods and someone who has lived in (and been priced out of) this type of housing in multiple neighborhoods around the city, I can assure the community council that it’s not what they fear. I currently live near the corner of 10th and Howe, in an older apartment building a block away from a single-family zone (along 10th Avenue West and Olympic Way West) that features just about every conceivable type of housing stock: multi-million dollar single-family homes, modest old brick ramblers, Craftsman homes that have been converted into multiple units, duplexes, triplexes, ADUs, DADUs, old apartment buildings, and brand new apartment buildings. While I’m sure the neighborhood isn’t immune to a parking or noise conflict here or there, for the most part it’s a wonderful place to live.

This is the “Missing Middle” that is increasingly lacking our city—modestly sized housing units that provide a middle ground between apartment living and homeownership, which is increasingly becoming a pipe dream for middle-class Seattleites. It’s also the kind of housing that may soon be allowed city-wide in Portland, but is apparently political kryptonite in Seattle.

This kind of housing has provided a perfect option for my wife and I. It’s allowed us to enjoy the benefits of living in neighborhoods that we otherwise wouldn’t be able to afford, being two young professionals who had the misfortune of the Great Recession occurring during our 20s. I don’t bring this up seeking pity, but only to serve as an illustration for how housing affordability affects the entire economic spectrum. We’re middle-class white people with dual income and no children; I can’t imagine what it must be like to watch rents rise for single parents, disadvantaged communities, the disabled, or those living on fixed incomes or Section 8 housing vouchers.

To hear the community council tell it, HALA’s proposed changes to single-family zones, including removing barriers to the construction of ADUs and DADUs, ignore the spirit of Queen Anne’s Neighborhood Plan and previous neighborhood planning processes.

Given the multiple stakeholders and viewpoints that go into their production, these plans inherently contain conflicting goals and policies. But the community council seems to be subjectively cherry picking which of the Neighborhood Plan goals and policies should be honored and which should be ignored.

QA-P5 reads:

Encourage an attractive range of housing types and housing strategies to retain Queen Anne’s eclectic residential character and to assure that housing is available to a diverse population.

With its opposition to efforts to encourage ADUs, DADUs, and other forms of housing diversity, the community council seems to be dismissing this goal out of hand.

The community council’s contention that ADUs/DADUs won’t provide affordable housing (Page 6) seems to misunderstand the benefit of adding this type of housing and is indicative of something that often gets overlooked in discussions about housing affordability—the middle class. To my knowledge, no one is contending that the owner of a single-family home will build an ADU or DADU and rent it out for $350 a month out of the goodness of their heart. (Though some very well may rent below market value for friends or family or in hopes of retaining a good tenant year to year.)

HALA contains many strategies aimed at providing housing for those that make 60% or less of median income, including the Mandatory Housing Affordability program, the expansion of Seattle’s Housing Levy, and direct investment in existing affordable housing stock. But the plan also speaks to the need to create additional market-rate housing for those at or around 100% of the median income, like my wife and I and thousands of other Seattle residents. A City survey found that most ADUs and DADUs rent between $1,200 and $1,800. A household making the city’s median income of around $67,000 and spending 25% of their income on housing would expect to pay about $1,400 a month on housing, making the DADU and ADU right in their sweet spot.

The concern about the role that short-term rentals such as Airbnb or VRBO plays on Seattle’s housing market is valid, and something that the City is currently seeking to address. But opposing the creation of new, moderately affordable housing stock because some of it may be used as short-term rentals overlooks that homeowners may be using that extra income from to help pay off mortgage costs. The City’s survey of DADU owners found that 43% of DADU owners found short-term rental income “very important” or “somewhat important.” Significantly more DADU owners (60%) said that the income from long-term rentals was “very important” or “somewhat important,” suggesting that more of these are being used as permanent rentals than vacation rentals.

QA-P12 reads:

Legal non-conforming uses exist in Queen Anne’s single-family neighborhoods, and these shall be allowed to remain at their current intensity, as provided in the Land Use Code, to provide a compatible mix and balance of use types and housing densities.

This goal seems to coincide with SF:1c in the HALA Plan (“Develop a clemency program to legitimize undocumented ADUs and DADUs”), which would help legitimize existing affordable housing stock in Queen Anne. By questioning these units’ “legal right to exist,” the community council appears to be suggesting that the duplexes, triplexes, ADUs, and DADUs that predate existing zoning code and were “grandfathered in” should be eliminated, which is surely the wrong direction to be moving during an affordability crisis in our city.

QA-P19 reads:

Promote methods of ensuring that existing housing stock will enable changing households to remain in the same home or neighborhood for many years.

ADUs and DADUs can play a vital role in helping meet this goal. ADUs and DADUs can provide flexibility for families that experience changing circumstances. There’s a reason they are often referred to as “mother-in-law apartments”—ADUs and DADUs can provide a separate living area for a child home from college for the summer or an ageing parent. The City’s survey found that 77% of DADU owners said that they built the extra unit for this reason.

They also make it possible for an ageing homeowner who wants to downsize to stay in the same neighborhood while renting out their primary residence. A DADU could also provide a place for an in-home care provider to stay. The City’s survey indicated that 32% of DADU owners said it was “very important” or “somewhat important” to have the extra unit to house a “live-in service provider such as a childcare provider, assisted living professional or property caretaker.”

QA-P29 reads:

Strive to diversify transportation modes and emphasize non-SOV travel within the Queen Anne neighborhood.

QA-P37 reads:

Strive to provide improved facilities for transit.

With limited public funds, transit agencies are often forced to prioritize service to the most productive routes based on ridership. On the east side of Queen Anne, King County Metro is currently in the process of consolidating the 3 and 4 routes into a combined corridor, making a longer walk to transit service for approximately 120 to 135 riders per day in single-family neighborhoods. Adding more residents to these areas puts Queen Anne in a better position to argue for more frequent transit service, particularly given its relatively close proximity to regional job centers like Downtown and South Lake Union.

Finally, the community council’s appeal of the City’s Office of Planning and Community Development Determination of Nonsignificance on this legislation questions the environmental implications of allowing more ADUs and DADUs in our community, but makes no mention of the largest environmental threat facing this generation—carbon and greenhouse gas emissions that contribute to global climate change. As Queen Anne residents, we are truly blessed to live in a walkable, bikeable, and transit-rich community that is in close proximity to job centers in Downtown and South Lake Union. Nixing potential housing units in our community does one of two things (and probably a little of both): it drives up the price of existing housing stock as more people compete for a fixed amount of housing, and it pushes residents who would prefer to live in Queen Anne to further flung neighborhoods and suburbs, where they are more likely to commute to work via more carbon-intensive transportation options. Land use and transportation is where the rubber meets the road on climate change, and as residents of a neighborhood well-suited to low-carbon lifestyles, we have a responsibility to the next generation to welcome more neighbors into our communities.

Calling Seattle’s rising rents a “crisis” isn’t hyperbole—by some metrics, Seattle is one of the only major metro areas in the country where the pace of rent increases is actually accelerating—from 8% in 2014-2015 to 12% in 2015-2016. Job growth in Seattle shows no signs of slowing in the immediate future, which means housing will be no less in demand in the coming years. Even at last year’s more modest 8% rate, we’re on pace to be at San Francisco levels (~$4,500 a month) in 8 years. I don’t believe that outcome—a beautiful coastal city that has no place for the middle class—is consistent with the community values of the Seattle that I know.

Even if Councilmember O’Brien’s optimistic projection of 4,000 new units city-wide becomes a reality, DADUs and ADUs alone aren’t going to solve our affordability crisis. But they do represent low-hanging fruit in the effort to provide more housing in our city. They provide more options for middle class Seattleites while respecting the aesthetic and architectural character of our existing single-family neighborhoods. The community council’s opposition to efforts to encourage this type of housing is inconsistent with many of the community’s stated planning goals and counter-productive in the fight to ensure that the middle class still has an outside chance at calling Seattle home in 2030.

Caleb Heeringa is a former journalist that has worked for the Bellingham Herald and Sammamish Review. He is pursuing Master’s Degrees in Urban Planning and Public Administration at the University of Washington. He likes his cities dense, his wilderness wild, and his baseball teams winning.