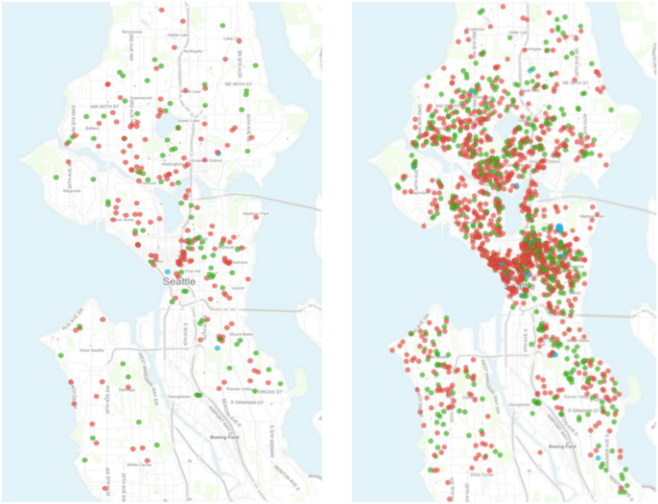

Short-term vacation rentals have become an increasingly prominent feature of the urban environment in Seattle. Just three years ago, there were only a couple hundred Airbnb listings in the city. That number has ballooned to well over 3,800 individual listings. Airbnb is not alone. Other short-term vacation rental services have also taken off like VRBO and HomeAway. But like any hot and innovative service, there are disruptive aspects to the traditional ways of doing business like rapid conversion of the existing housing stock to vacation rentals, lost tax revenues, and lack of compliance with health and safety protections. That’s why Councilmember Tim Burgess is proposing new regulations on short-term vacation rentals.

Short-term vacation rentals often share similarities with traditional bed-and-breakfast accommodations, but run the gamut from a spot on someone’s couch to a full seaside villa.

Councilmember Tim Burgess’ office began researching the issue of short-term vacation rental regulations last year. His office looked at peer cities across the country that have already enacted local laws on the topic. Some cities have narrowly focused on enforcing requirements for taxation and business licenses. Others have adopted strict controls on the location of short-term vacation rentals, number of nights allowed for renting, and the relationship between the operator and units being rented. New York City prohibits renting units for fewer than 30 days, making it illegal to operate a short-term vacation rental. New Orleans is tougher restricting rental terms shorter than 60 days in the French Quarter and 30 days elsewhere in the city. And in Santa Monica, an operator of a short-term vacation rental must live on the property to be rented whenever there is a short-term stay.

Many cities have also adopted regulations that offer greater flexibility, but still tackle core policy goals that their communities believe are valuable. For instance, a short-term vacation rental operator can rent up to 180 days per year without an on-site host present in San Jose. With an on-site host, a short-term vacation rental can be operated year-round. Philadelphia takes a different approach using fewer days and requiring a special license in certain cases. An operator can rent up to 90 cumulative days in a 12-month period without a special license. Between 90 and 180 cumulative days in a 12-month period, a short-term vacation rental operator has to obtain a special license and commit to owner occupancy of the unit.

Councilmember Burgess is sponsoring legislation that more closely resembles the legislative intent of cities like San Jose and Philadelphia. According to his office, most short-term vacation rental operators (about 80%) let their spaces 90 nights or fewer in a given year. The proposed legislation would therefore only add new regulatory requirements for about 20% of the operators in Seattle. Some of these short-term vacation rentals may have to shut down (e.g., multi-unit Airbnb condos and apartments) and others may only need to adjust their business plans to conform with the rules.

What the legislation would do

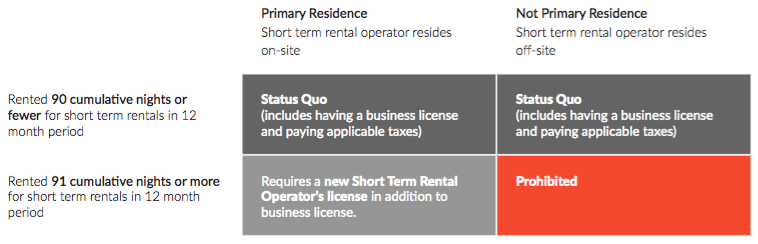

Under Councilmbmer Tim Burgess’ proposal, short-term vacation rentals1 would be regulated differently depending upon two factors:

- The number of nights that a unit is rented; and

- Whether or not the operator resides at the primary residence2 of the unit(s) being rented.

In sum, a unit can be rented up to 90 cumulative nights in a 12-month period at a primary residence or accessory dwelling unit of the operator or at a secondary residence. Beyond 90 cumulative nights in a 12-month period, a unit could only be rented at the primary residence or accessory dwelling unit of the operator; renting any other non-primary residence would be prohibited. Additionally, any operator renting a unit more than 90 cumulative nights in a 12-month period would be required to obtain a Short-Term Rental Operator’s License and meet specific health, safety, and reporting requirements.

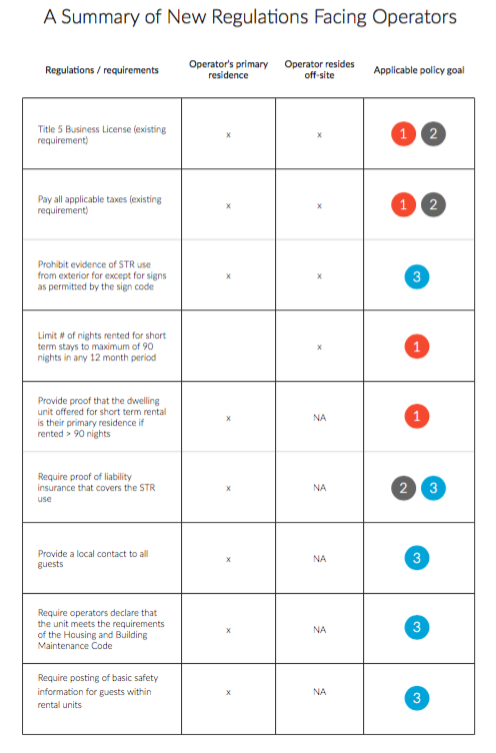

Operators that would be subject to the Short-Term Rental Operator’s Licence would need to meet the following requirements:

- Provide proof that the unit being rented is their primary residence;

- Provide a local contact and post basic safety information for guests;

- Hold liability insurance covering short-term vacation rental use; and

- Ensure that the unit meets all building and life safety codes and sign a declaration attesting that the unit meets the Housing and Building Maintenance Code.

For individual operators, the legislation would also clarify other requirements:

- Signage associated with the short-term vacation rental business would be prohibited by the City’s sign code, except where otherwise allowed.

- Many short-term vacation rental operators have failed to obtain a basic business license. The proposed regulations would clearly spell that out and require operators to pay the sales tax.

- And, the total number of residents and guests occupying a dwelling unit where a short-term vacation rental is present would not be able to exceed the maximum number of residents allowed in a household. The Seattle Municipal Code defines this as eight unrelated persons or fewer. The legislation would extend the same household number maximum even for properties that may rent out an accessory dwelling unit. In other words, the City would count the number of persons allowed on aggregate between the primary dwelling and accessory dwelling unit.

To further the goal of enforcement of the new regulations, the legislation would also require the cooperation of short-term vacation rental platforms like Airbnb and VRBO operating in Seattle. The draft legislation doesn’t cover this, but Councilmember Burgess’ policy briefs point toward rules that would compel the companies to share their data with the City and obtain company operator licenses. Reporting would be required on a quarterly basis to provide basic information like the names and addresses of registered short-term vacation rental operators and the number of nights that each operator has rented on the platform over the previous 12 months.

The legislation would also alter the regulatory framework for bed and breakfast (B&Bs) lodgings in order to bring those establishments more on par with short-term vacation rentals. Previous rules governing them like the amount of ownership interest in a B&B, restriction on non-family employees, minimum age of a residence required to establish a B&B use, and others would be repealed. However, no new B&Bs would be permitted, forcing new operators to enter the market under the applicable short-term vacation rental framework instead. In fact, the draft legislation would not recognize any new B&B uses that weren’t lawfully established3 before May 1, 2016 (though this date could change in committee). In single-family zones, newer B&Bs would be limited to five guest rooms whereas older B&Bs (established before April 2, 1987) in single-family zones or B&Bs in multi-family zones would have no limitation on the number of guest rooms.

What the legislation won’t do

No new taxes would apply to short-term vacation rentals. That’s because the City only has authority to institute a special tax (Convention and Trade Center Tax is 7.0%, in addition to the base sales tax) on lodging businesses if there are 60 or more rooms. Technically, all proprietors are subject to a business license and the basic taxes associated with procuring and renewing the license. The new legislation would require all proprietors to get a business license, but most won’t be subject to the Business and Occupation Tax (B&O Tax), which is only levied on companies with gross revenues at $100,000 or greater. The average homeowner won’t get anywhere close to that kind of annual revenue. In absence of a B&O Tax, short-term vacation rentals are only subject to the basic sales tax.

Next Steps

Councilmember Tim Burgess will discuss legislation a the Affordable Housing, Neighborhoods, and Finance Committee today (Wednesday, June 15th), a committee he chairs. A final committee vote on the bill is anticipated in July, allowing further consideration by the full Council sometime afterward.

Footnotes

- Under the proposal, a “short-term rental” would be defined as a lodging use that is neither a hotel nor motel and where a dwelling unit or rooms within a dwelling unit are rented to an individual or individuals for 30 consecutive nights or fewer. Rentals that are 30 consecutive nights or greater are deemed long-term in keeping with the City’s long-term tenant laws.

- The City intends to define “primary residence” as a resident’s typical place of long-term housing and would require that an operator of a short-term vacation rental produce documentation to corroborate their primary place of residence. An owner can’t have more than one primary residence.

- To qualify as “lawfully established,” the use would have to have been established by certain permits from the City, Seattle King County Public Health, or Washington Department of Health and not discontinued in activity for more than one year.

Stephen is a professional urban planner in Puget Sound with a passion for sustainable, livable, and diverse cities. He is especially interested in how policies, regulations, and programs can promote positive outcomes for communities. With stints in great cities like Bellingham and Cork, Stephen currently lives in Seattle. He primarily covers land use and transportation issues and has been with The Urbanist since 2014.