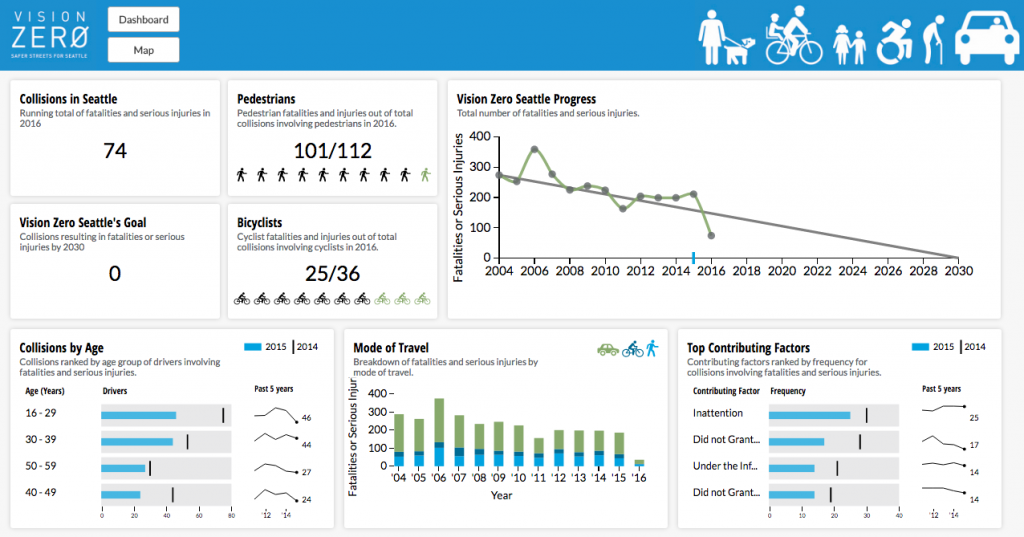

The Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) has been on a marketing blitz lately promoting Vision Zero. There have been Facebook ads, web videos, and radio spots encouraging drivers to put their cell phone out of reach while on the road to reduce distracted driving collisions. And this week they have released a new web tool, the Vision Zero Dashboard.

The Vision Zero Dashboard, like the ad campaign, focuses the brunt of outreach toward achieving zero serious injuries and fatalities on the user, be they a person on foot, in a car, or on a bike.

But the reason Vision Zero was successful in Sweden, where it was developed, is that it focuses on the road design needing to accommodate the fact that the road user might fail at any given moment and cause a crash. Vision Zero takes it as a given that we will not be able to reduce collisions. The metrics included in the Vision Zero dashboard are lagging indicators of the safety of our road spaces: they are more symptom than diagnosis.

I would liken focusing on personal responsibility when talking about Vision Zero is like launching a campaign that aims to completely eliminate all cigarette smoking in the US with the aim of improving public heath. Sure, a campaign could reduce the instances of smoking by educating the public, and we have seen that in the past few decades as smoking use has plummeted. But to get to zero, a different approach would be required: a systemic look at how the system is designed that allows that behavior in the first place.

The real Vision Zero is actually in a different location on SDOT’s website: the Capital Projects Dashboard. According to that website, SDOT’s capital projects are 100% on schedule and 95% on budget. That only counts as true if you are examining the Bike Master Plan Implementation Schedule for 2016 in a vacuum. But despite having passed a massive levy last year for transportation projects like protected bike lanes, the 2016 project list is dramatically scaled back from previous years’ plans.

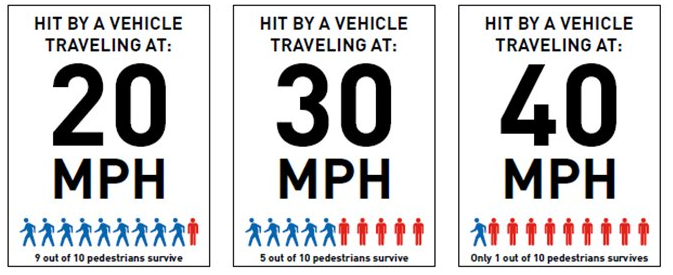

I am mentioning bike projects specifically as key Vision Zero projects because in addition to providing dedicated safe space for bikes, they typically enhance the pedestrian environment at the same time. Finding space for bike lanes generally means redesigning the lanes on our arterial streets, and the width of lanes is one of the largest contributing factors that determine a driver’s speed. This plays a direct role, obviously, in how likely a person is to survive a crash. A dashboard allowing the user to track where vehicle lane widths have been reduced would be one of the best leading indicators of Vision Zero progress.

The City even has a new website promoting the best piece of bike infrastructure in Downtown Seattle, the Second Avenue bike lane, as it prepares to expand it north to Denny. What the nicely produced video does not mention is that there is no real easy way to bike to either end of this protected bike lane, and that the lane is frequently closed with no notice from SDOT’s Twitter page or website. Inconsistent infrastructure is not safe.

Road design and personal responsibility will both play key roles in reducing injuries on our roads. But when we talk about Vision Zero, we must realize that in order for it to be successful, it’s not as easy as putting your cell phone in the glove compartment. We need to change our entire approach to road safety.

The featured image header is courtesy of Andres Salomon, a Northeast Seattle safe streets advocate.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.