Last week, draft recommendations on the University District rezone and urban design proposal were released. We provided a high level overview for many of the policy elements in the proposal like development regulation, incentive zoning, and mandatory affordable housing. But the proposals are worth deeper analysis. In this piece, we’ll look at the special neighborhood development regulations that the Office of Planning and Community Development (OPCD) is evaluating for the SM-U zones.

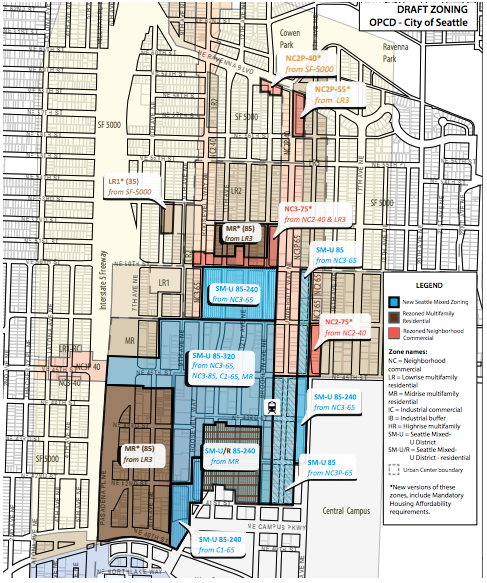

To recap, the rezone proposal is essentially broken into three buckets of zoning: Seattle Mixed-University District (SM-U), Neighborhood Commercial 2 and 3 (NC2/NC3), and Midrise (MR). Each zoning typology is directly tied to specific development standards that manage urban design, like landscaping, architectural massing, site amenities, and setbacks. But it is the SM-U zone that has the most proposed changes from an urban design perspective. Areas proposed for NC2, NC3, and MR rezones will generally be subject to existing development code requirements.

Building And Urban Design Proposals For The SM-U Zones

Many of the comments received throughout the policy development process focused on building and urban design issues. New development taking shape in the neighborhood has tended to be quite boxy and bulky. Some structures have even exceeded facade widths of 300 and 400 feet. With that in mind, OPCD is recommending a variety of development regulations to encourage building design that is more appealing and amenable to the pedestrian realm.

One way to tackle design is through building width and depth. Downtown Seattle’s average block size is 240 feet by 240 feet while blocks in Portland’s Pearl District are 200 feet by 200 feet. Compare that to the long north-south blocks in the University which are typically around 500 feet by 220 feet. OPCD is recommending that the width and depth of buildings is no more than 250 feet on any given block. Only certain uses like community centers, religious institutions, light rail stations, and schools would be exempt from the requirement.

In a similar fashion, OPCD proposes to regulate the modulation of building facades on sites that are 12,000 square feet or greater in size. The modulation standards differ depending upon the height of a structure and at various levels of the facade. For instance, the first 45 feet of vertical height for an 85-foot tall building could only remain unmodulated if it had a frontage width of 120 feet or less. Meanwhile, the height above 45 feet for the same building could only remain unmodulated if it had a frontage width of 80 feet or less. Ultimately, buildings that are tall and wide will likely to be subject to the modulation requirements so as to create a more interesting aesthetic as opposed to blocky development.

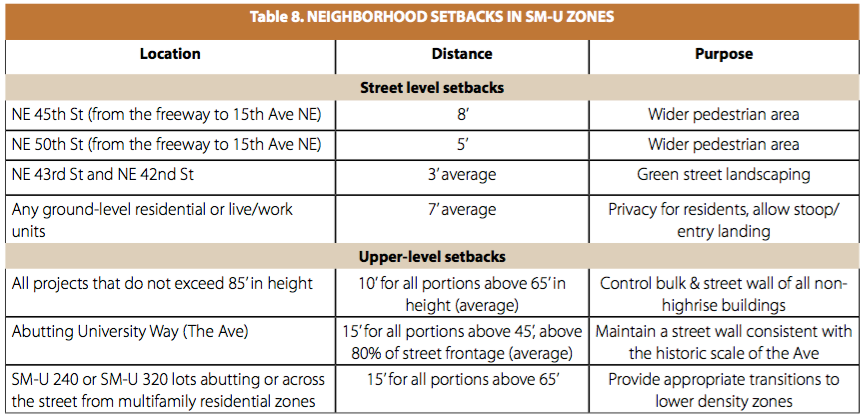

Another way to address building design is by controlling development through setbacks. OPCD is proposing to do this in two ways: street-level setbacks and upper-level setbacks.

The impetus to control street-level setbacks is partially to improve the flow of pedestrians on sidewalks, partially to beautify the streetscape, and partially to let the ground floor frontage of buildings breathe. Wider sidewalks means that sidewalk cafes, planter strips, and seating all become options in addition to just moving people on foot. Streets throughout the University District today often have very heavy foot traffic, especially on main commercial thoroughfares like University Way NE and NE 45th St. As the neighborhood becomes denser and with the arrival of light rail, the tight walking conditions will only get tighter. That’s why OPCD is recommending additional setbacks at street-level for new development. The setback amounts aren’t substantial, but they will go a long way toward reducing crowding on what would otherwise be narrow sidewalks:

As part of the street-level setbacks, new development will generally have to construct frontage improvements that meet the standards of the neighborhood’s Green Street plan where applicable:

The street-level setbacks do allow for some flexibility. For instance, bay widows, balconies, and copies could extend up to 4 feet into any required setback above the street, giving developers some latitude to create visually interesting facades and utilize more space. For ground floor residential units and live/work units, the setback requirements are geared toward offering residents a little more semi-private space and defense from the street. Private amenity space and stoops are encouraged with landscaping to make the space between a residence and street feel comfortable.

The proposal also goes with upper-level setbacks for new development. The upper-level setbacks are again tied to the concept of improving the pedestrian realm experience by reducing the bulk of structures that are taller than 65 feet. At ground level, the pedestrian’s eye is mostly focused on the first few floors of a structure. Portions of buildings “hidden” behind the apparent “top” are less noticeable or even invisible if done well—a technique widely used in Old World cities like London and Paris to great effect. The modest setbacks will ultimately help make blocks feel more airy and lighter.

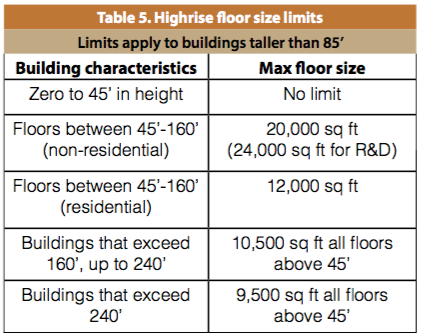

Tower location and floorplates are proposed to be managed in a number of ways. Firstly, new highrise towers (structures over 85 feet in height) would only be allowed on sites that are 12,000 square feet or greater in size. Secondly, highrise towers would have to attain a separation of 75 feet from the nearest existing or approved tower. Thirdly, the floorplate of towers would be different depending upon the type of use and height. Generally, residential towers under 16 stories would have to be built with smaller floorplates than office towers, a requirement partially meant to achieve better lit units and match the smaller footprint that residential towers have. Towers that exceed 16 stories would have to be progressively more slender in the size. But considering that FAR requirements are also tied to towers, the floorplate maximums may not necessarily matter so much if a developer wants to go the full highrise route.

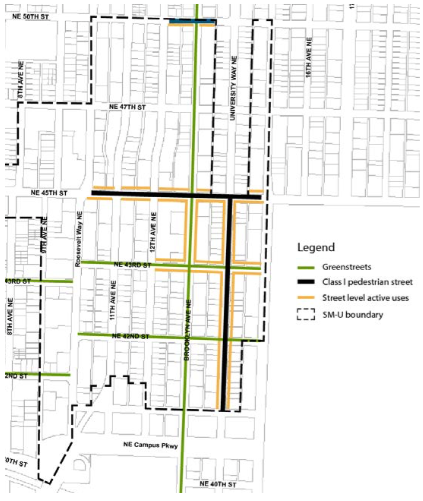

In order to create vitality and street interaction throughout the SM-U zones, OPCD is proposing requirements for active street-level uses, building transparency, and overhead weather protection:

- Active street-level uses would be required to be located on at least 75% of any frontage along street indicated in the map below (noted with yellow lines). The kinds of uses include restaurants, retail and services, entertainment, and similar active uses. Spaces created for active ground floor businesses would have to be built with high ceilings (13 feet floor-to-floor) that go deep into a unit (minimum depth of 30 feet) and have access to a sidewalk or open plaza. The idea with these provisions is to create accessible, sizeable ground floor units that could allow for a variety of uses (e.g., clothing stores and restaurants) over time and more closely mimic historic storefronts seen in neighborhoods.

- The transparency and blank facade standards apply to all streets within the SM-U zones. Generally, a minimum of street-facing facades would have to be transparent—that means lots of clear or lightly tinted glass in windows, doors, and and display areas along facades. Blank facades would also be limited to a maximum width of 15 feet on any given portion of a structure. The intent with this provision is to encourage architectural features, artwork, and other elements to make facades visually interesting.

- Overhead weather protection (e.g., canopies, marquees, and arcades) will generally be required along 60% of a street facade. The intent of the requirement is to ensure that pedestrians have comfortable spaces to walk through by protecting them from the elements that can sometimes be quite harsh in Seattle (winter downpours!) and driving more foot traffic in all weather conditions.

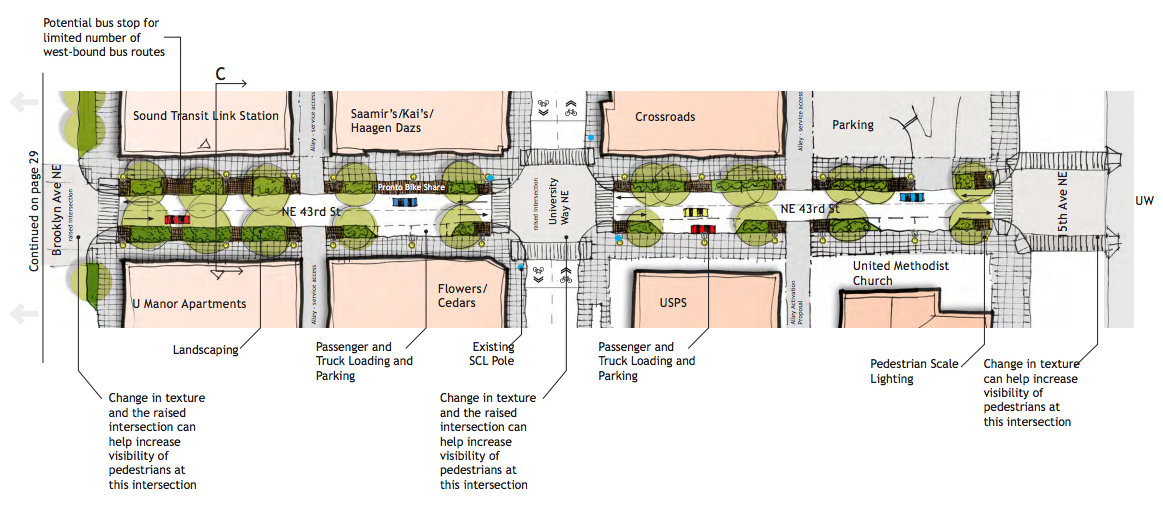

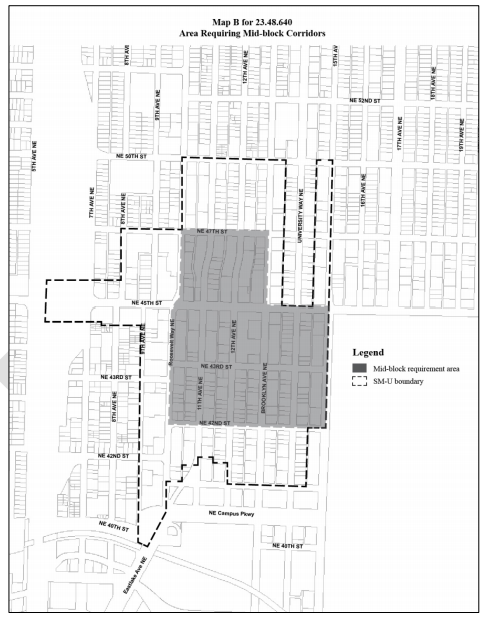

Responding to the problem of long blocks with little permeability in the University District, OPCD is recommending that larger developments be required to provide mid-block through connections. A secondary benefit of the requirement is that it will help ensure that scale of development is broken up. Mid-block through connections will only be required on sites that exceed 30,000 square feet in area, abut two north-south streets (even in instances were a development proposal would straddle an alleyway), and has a street frontage of 250 feet or more on the north-south streets (there are a few exceptions to the requirement). Where required, the mid-block through connections will have to meet a number of standards, including:

- A continuous connection between both north-south streets;

- Be no closer than 150 feet to the nearest east-west street;

- Generally be constructed at a flat grade to provide a visual connection through and for accessibility;

- Have an average width of 25 feet, but can be reduced to a minimum of 15 feet;

- Provide at least one open space area (minimum size of 1,500 square feet);

- Remain generally unobstructed to the sky (only 35% of a corridor could be cover or enclosed); and

- Have a comprehensive lighting program that ensures the corridor is lit during public use.

Finally, OPCD is recommending stricter controls on parking facility designs. On smaller sites, parking would need to be fully separated at street level by other uses to hide the parking facilities. Larger development sites could reduce the requirement to 30% of street frontage as long as the parking facilites are fully screened from the street. In effort to prevent dead corners, other uses at the street level would always be required at the corner of a parking facility when located at an intersection. It’s also worth noting that there are generally no car parking requirements within the area, but OPCD wants to reduce the proliferation of parking by setting a maximum parking rate of one stall per 1,000 square feet of gross floor area for non-residential uses. The primary goal of these regulations is to keep the public realm lively and attractive.

Next week, we’ll wade into how incentive zoning, transfer of development rights, historic preservation, and mandatory affordable housing play a role in the proposal.

If you wish to comment on the proposal, contact OPCD at udistrict@seattle.gov. Or participate in one of the drop-in sessions over the next two weeks with City staff.