Storefront establishments form the bedrock upon which successful urban, walkable communities are built. Seattle happens to be one American city well known for its tightly-knit and vibrant neighborhood business districts. But the larger Puget Sound metropolitan region has far fewer examples of walkable neighborhood business districts beyond other old peer cities like Tacoma and Everett.

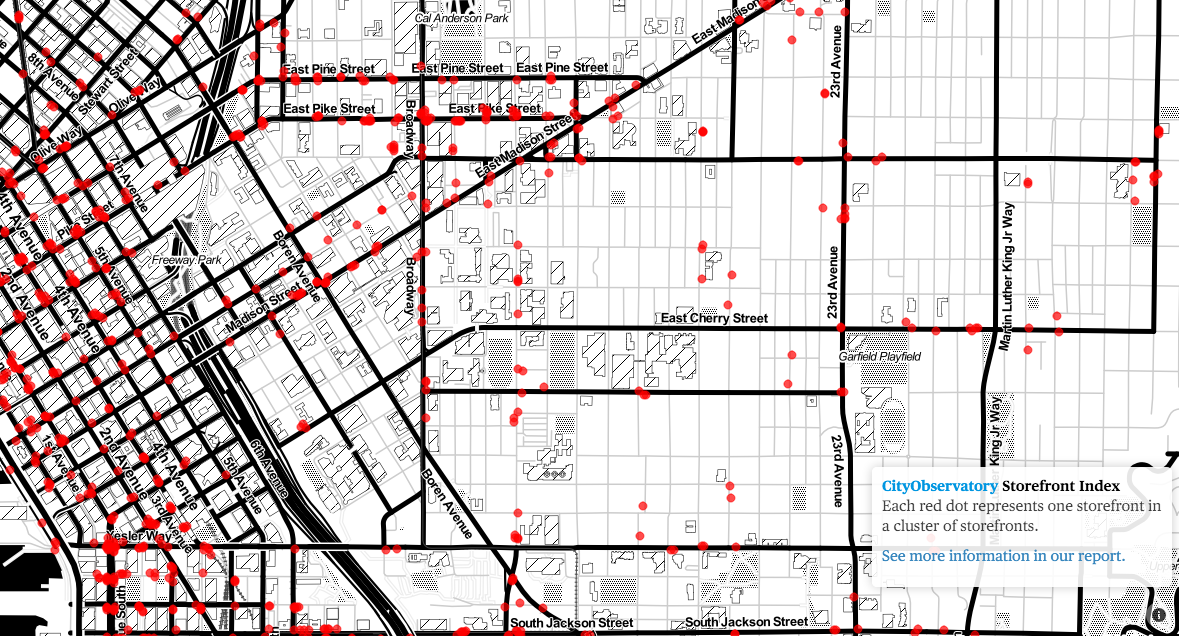

City Observatory has created what they call a “Storefront Index“, which is both a mapping tool and a true index that offers a window into key retail characteristics within a metropolitan region and between peer regions. It’s often very difficult to compare place to place from a qualitative standpoint, but breaking storefronts down into absolute numbers and location gives a good framework to understand how places perform differently with storefront retail.

With a little analysis, it’s possible to make assumptions development patterns, neighborhood walkability, and level of retail diversity all without ever stepping foot into a retail district. City Observatory‘s Storefront Index does this by measuring the density of storefront retail establishments across 51 metropolitan areas in the United States. The index broadly defines “retail” with everyday uses ranging from grocery stores and restaurants to beauty salons and entertainment venues. To truly capture density patterns of storefronts, the index only counts storefronts when two or more storefronts are located within 100 meters of each other.

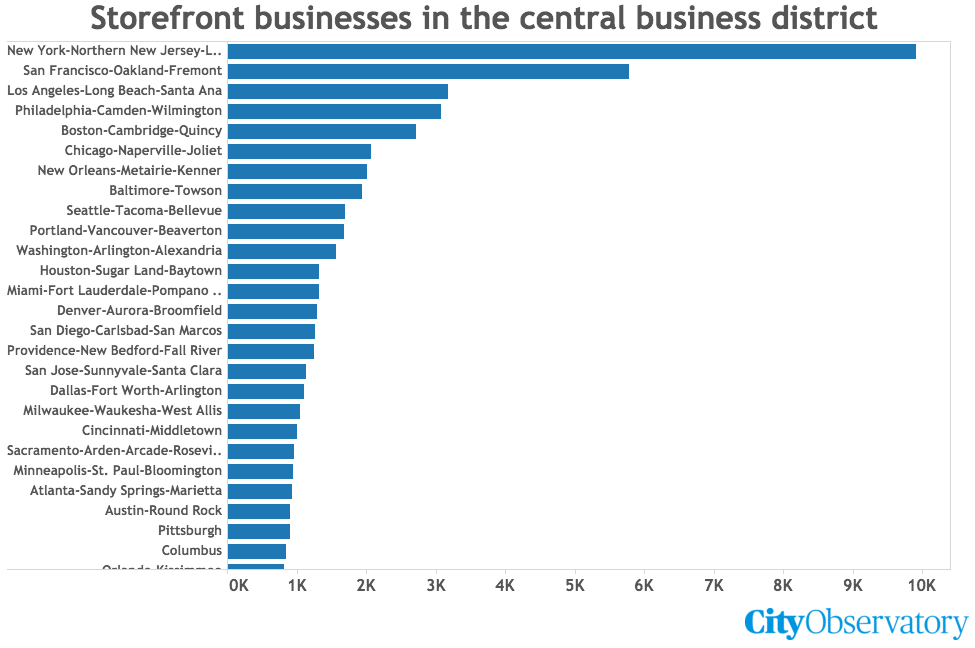

Seattle ranks highly amongst peer metropolitan regions in the Storefront Index. The index estimates that there are some 1,694 storefronts in proximity to the central business district (CBD)—just edging out Portland and Washington, D.C. for ninth place in the top 10. City Observatory‘s index uses the same approach to measure CBD storefront density across metropolitan areas: All storefronts within a three-mile radius of a city core are counted regardless of other considerations. So it is possible that Seattle could have a higher density of storefronts than Baltimore, for instance, controlling for natural features like waterbodies within the radius.

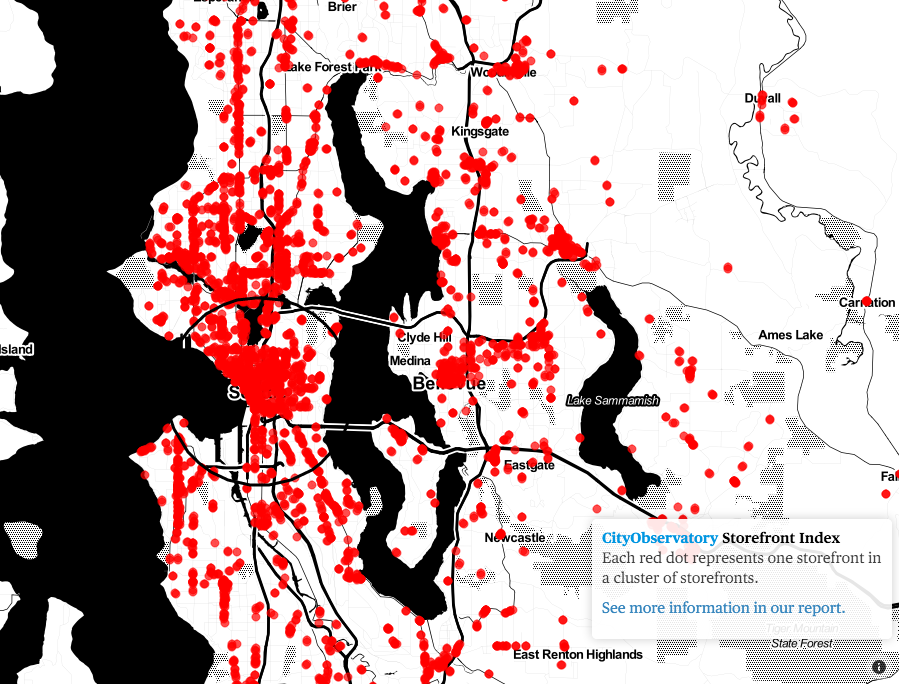

At a high regional view, Seattle very clearly has far and away the highest density of storefronts. In fact, it would appear that it may have the most storefronts in absolute terms in King County. Looking at the regional level presents some obvious patterns:

- Clusters of storefronts appear close to city centers and coveted shopping districts (e.g., Phinney Ridge, University Village, and Beacon Hill);

- The density of storefronts rapidly declines away from the city and district centers;

- Far flung suburbs and rural areas have little if any measurable amounts of storefront, and where they do, the density appears to be quite limited; and

- Clusters are nearly continuous along long-established corridors between cities (e. g., SR-99 from Downtown to Lynnwood, SR-522 from Maple Leaf to Bothell, and Rainier Avenue from Pioneer Square to Renton).

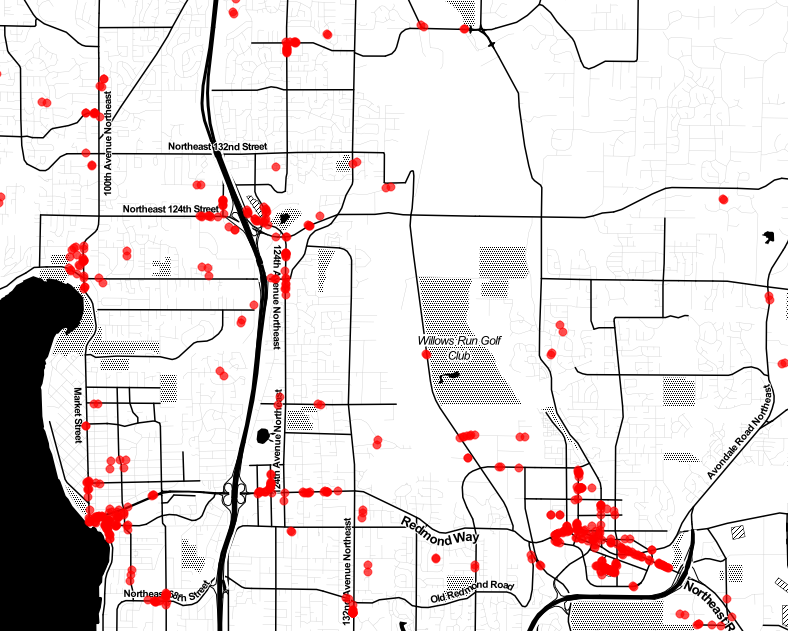

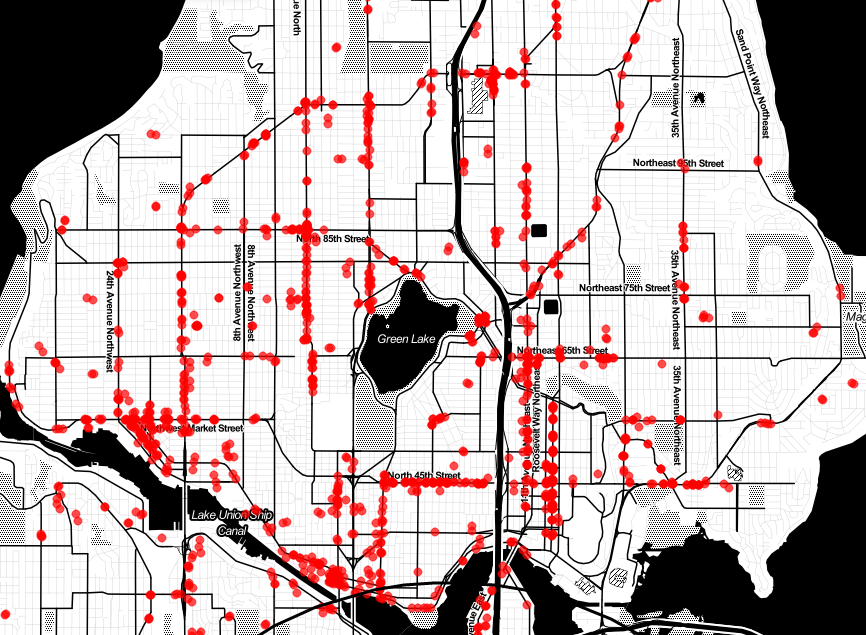

Drilling down further, it’s possible to see the finer grain differences in storefront density from one block to another:

Note that the scale of the Eastside and North Seattle communities are the same, yet the patterns are very different. The density of storefronts on the Eastside are primarily located in city centers and to a lesser degree at key neighborhood intersections (e.g., Juanita, Totem Lake, and Houghton). In North Seattle, the pattern is much more persistent with storefronts often running full corridors (e.g., Stone Way, Roosevelt Way, Phinney Ave/Greenwood Ave) and at primary intersections (e.g., NE 75th St & 35th Ave NE, and NW 80th St & 24th Ave NW). In other words, storefronts are much more ubiquitous across North Seattle neighborhoods than their Eastside counterparts.

These differences aren’t exactly surprising when you consider their contexts. North Seattle was primarily developed as streetcar suburbs (south of 85th St) while Eastside communities are generally the result of post-war auto-centric suburbs (excluding their city centers). Streetcar suburban development often resulted in linear commercial development at stops so that people could shop close to where they lived and walk home. Post-war auto-centric suburban development largely did away with storefronts in the traditional sense and instead instituted more limited strip commercial development, malls, and large-scale big box retailers.

Zooming in closer to Downtown Seattle and First Hill/Capitol Hill and it’s possible to see how pervasive storefronts are in these urban neighborhoods. Almost every block in Downtown Seattle has numerous storefronts that open up to the street and it’s the same on main thoroughfares of Capitol and First Hill (e.g., Pike/Pine, Broadway, and Madison St). But what’s also interesting is how quickly the density of storefronts can drop off. Go a block north or south of Pike/Pine, and you’ll be hard pressed to find a storefront. In the urban context, this suggests that zoning or other constraints are likely at play leading to the lack of storefronts beyond these retail centers.

Aside from my observations, what other patterns do you see?

Stephen is a professional urban planner in Puget Sound with a passion for sustainable, livable, and diverse cities. He is especially interested in how policies, regulations, and programs can promote positive outcomes for communities. With stints in great cities like Bellingham and Cork, Stephen currently lives in Seattle. He primarily covers land use and transportation issues and has been with The Urbanist since 2014.