The City of Seattle has cut back significantly on its plans for street safety projects citywide, but especially in Downtown and the southern neighborhoods. This has left advocates confused and frustrated, as the City had extensive plans for protected bike lanes and greenways that would create a comprehensive network. And voters just overwhelmingly approved a $930 million levy to build these projects. While that is sorted out and the City adds on another layer of Seattle Process with a “Center City Mobility Plan”, there is one key opportunity that we could implement today at low cost: redesigning 4th Avenue through Downtown.

4th Avenue is a northbound one-way street and is among the widest streets in Downtown. Not surprisingly, it carries the highest amount of vehicle traffic in Downtown—but not so high that bikes lanes are infeasible. According to the latest counts from the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT), between Yesler Way and Stewart Street average annual weekday traffic (AWDT) is 20,600 vehicles. North of Stewart Street to Denny Way, in the Belltown neighborhood, AWDT lowers to 14,100.

These numbers along with the street’s use as a regional transit corridor and existing use by bicyclists, make the street ripe for a reconfiguration.

Current design

The existing design struggles to balance many needs. Like most of the Downtown streets, 4th Avenue is home to many ground level retail spaces, hotel lobbies, restaurants, and parking garage entries that draw private motorists and taxis but which also demand ample sidewalk space. The street also fronts major civic spaces like City Hall, the Central Library, and Westlake Park. On-street parking is located throughout.

At the same time, 4th Avenue is a major bus corridor for regional Sound Transit and Community Transit routes and has a peak-hour bus lane. These buses tend to exit 4th Avenue at Olive Way, which leads to on-ramps for Interstate 5. And because the street is relatively flat through Downtown, it’s also a popular route for people riding bicycles.

The most important consideration in street design is how much space is available, so we’ll quickly run through what we have to work with (thanks to this handy SDOT arterial list). The table below summarizes the right-of-way widths:

From the roadway width and knowing how many lanes currently exist, we can estimate how much space is allocated to each lane. The graphics below, generated with streetmix.net, generalize the existing conditions in Downtown and Belltown.

The upper image ignores an existing unprotected bike lane that only runs between S Washington Street and Spring Street next to the curb, pictured below.

The vehicle lanes are already below the standard of 12 feet, a good start that helps keep traffic speeds down. But there are more lanes than needed; as demonstrated by Seattle’s road diet criteria, traffic volumes less than 25,000 only require two drive lanes. In the Downtown portion, there are three drive lanes during most of the day and four to five drive lanes, including a bus lane, during peak hours. On the wider portion of 4th Avenue in Belltown there are no restrictions on the two parking lanes, resulting in four drive lanes all day long even though traffic volumes are lower there.

An excellent example of 4th Avenue’s excessive capacity has been illustrated when the left lane between Pine Street and Olive Way is closed for the Macy’s store renovations. Despite the reduction in capacity during the afternoon rush hour, through-traffic continues to move at a steady pace. See below for a video of this in action.

In addition, the left lane of 4th Avenue is hardly used by through-traffic during the afternoon peak anyway. This may be because most drivers are headed north or to Interstate 5, which ultimately requires a right turn. Bicyclists take advantage of this situation and have de facto taken over the left lane, illustrated in the (admittedly anecdotal) photo below.

The recent redesign of 2nd Avenue, the southbound counterpart to 4th Avenue, provides another case study. 2nd Avenue replaced a painted bike lane and one drive lane with a two-way protected bike lane in 2014, and now during peak periods a standard block has two drive lanes, a bus lane, and an alternating left-turn lane and parking lane. Bicycling traffic has tripled since the implementation and vehicle traffic flows smoothly. 2nd Avenue carries 75-85 percent of the traffic that 4th Avenue does, so a similar approach should work.

A multi-modal solution

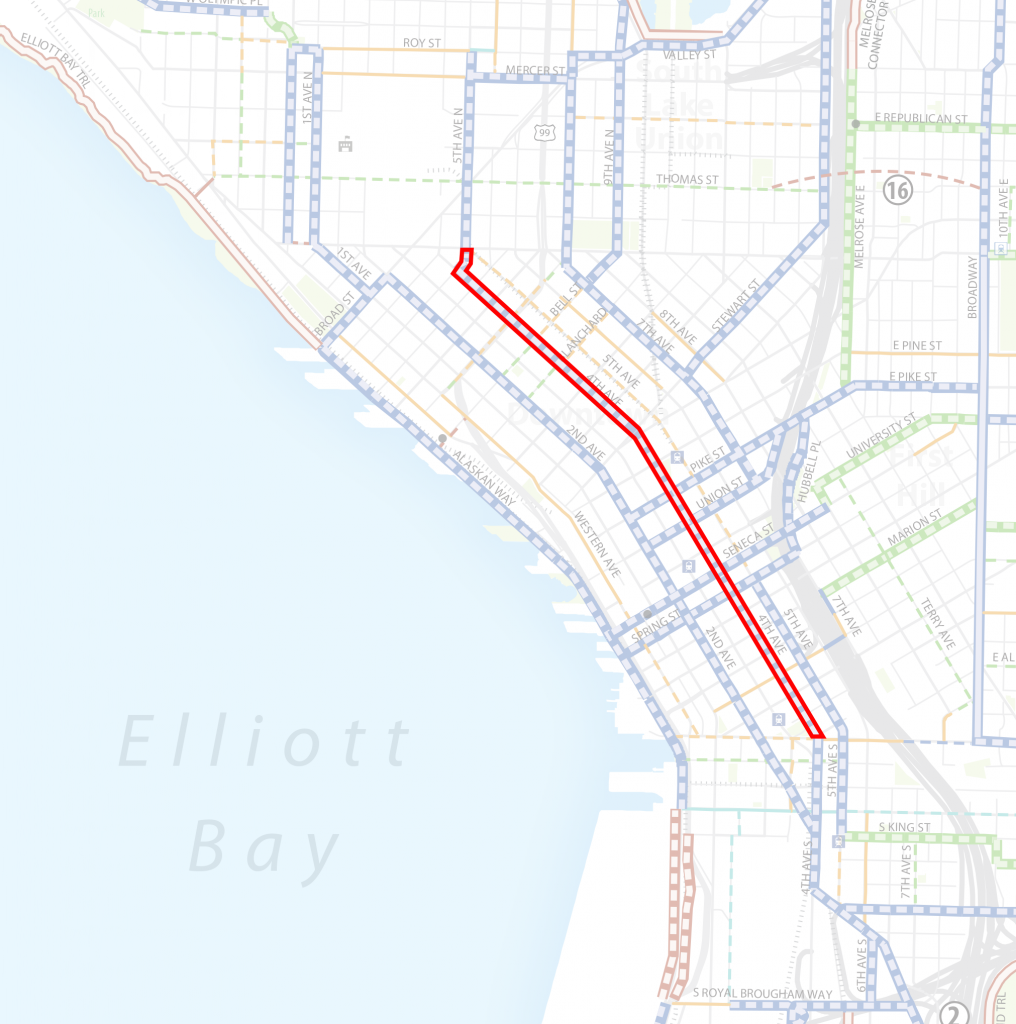

The proposal in Downtown is to reallocate space on a 1.5-mile stretch of 4th Avenue for a two-way protected bicycle lane, a permanent bus-only lane, and one lane of permanent on-street parking. This leaves two drive lanes for general traffic; this should be plenty of capacity most of the time on weekdays and weekends. Afternoon peak periods may experience a slight increase in travel time, but this is a worthwhile trade off considering the benefits to bicyclist safety and transit speeds.

In Belltown, where buses don’t run on 4th Avenue, two lanes of permanent on-street parking can remain. The awkward curb-to-curb width doesn’t permit only one drive lane to be removed, though, so two are removed and two remain. The extra six to eight feet of space could be used to widen the bike lanes, widen the buffer, or do something more creative like constructing a row of parklets or adding landscaping, similar to an idea floated by SDOT for 5th Avenue.

Side note: If 4th Avenue is redesigned as proposed there isn’t much reason to implement a PBL on 5th Avenue because it’s only one block away. But the spacing between 2nd Avenue, 4th Avenue, and the future bike facility on the waterfront suggests the opportunity to create an easy-to-understand bike network with safe facilities on every other block; 6th Avenue and 8th Avenues are also relatively wide streets that could easily fit two-way PBLs through Downtown and Belltown.

The two-way PBL is a critical component of the proposals, as it legitimizes the heavy bicycle use of 4th Avenue and will encourage more people to bike by creating a safe route through the center of Downtown. I’d wager it would get even more use than the 2nd Avenue PBL because it is more central and it is higher up on the Downtown slope.

One look at SDOT’s official parking map also shows how these changes would benefit businesses and other drivers by simplifying the parking situation. Instead of a weave of on-street parking spaces that are prohibited during peak hours, these layouts would create permanent parking lanes and loading zones that can be used all day. This makes the rules easier to understand and could reduce the clutter from parking signs.

In addition, the permanent parking lanes and the PBL significantly narrow the main roadway, benefiting pedestrians with shorter crossings at intersections. There is also new space for landscaping, bollards, or concrete curb extensions that could further reinforce intersection corners and help give people walking and driving better views of each other.

North and south connections

Of course, it’s not enough to stop here. The 4th Avenue bike lanes need to connect to the rest of a robust network.

In the north, the Bicycle Master Plan indicates a protected bike lane on 5th Avenue and the east side of Seattle Center. This looks like a good connection point, as it would cross the paths of a planned greenway on Thomas Street and the existing bike facilities on Mercer Street and Roy Street.

In the south is a more interesting issue. Seattle Bike Blog has noted that the Yesler Bridge project will widen the existing unprotected bike lane below the bridge, but planners didn’t go further and make accommodations for a future two-way facility. However, the west sidewalk under the bridge is quite wide could have some space reallocated for the southbound bike lane.

Moving further south, the Bike Master Plan shows a continuation of the 4th Avenue bike route intersecting with an extension of the 2nd Avenue PBL and new PBLs on 6th Avenue and Dearborn Street. It would continue on to Airport Way S, which form a backbone through Sodo and Georgetown.

Other needed improvements

To complement this 4th Avenue makeover Olive Way also needs a small fix for buses. There’s a bus lane on most of Olive Way towards I-5, but there is a one block gap between 4th Avenue and 5th Avenue. This gap needs to be filled with a permanent extension of the bus-only lane to give buses greater priority through those intersections.

In addition, to make a more complete safe bicycling network Downtown also needs at least one major east-west protected bike lane. The best opportunity for that is either on Pike Street or Pine Street, which reach across I-5 to Capitol Hill on relatively shallow slopes and are fairly central to Downtown. Both streets are transit routes and have on-street parking, so a creative solution will be explored in a future post.

Another option would be a two-way PBL on Olive Way, but that street has a three-lane pinch point on the I-5 overpass and would likely impact traffic movements that are under the jurisdiction of the bureaucratic Washington State Department of Transportation.

Conclusion

People bicycling and walking are getting hurt and killed on our Center City streets nearly every single day. With the City’s supposed commitment to Vision Zero, soon to be in the spotlight with the NACTO conference in September, it’s time for Mayor Murray and the Seattle Department of Transportation to make bold decisions and complement critical links in the safe bicycling network. 4th Avenue is major street in the core of Downtown and Belltown that can become more accessible, safe, and efficient for everyone that uses it, but only if our leaders step up to the challenge.

This article is a cross-post from The Northwest Urbanist.

Scott Bonjukian has degrees in architecture and planning, and his many interests include neighborhood design, public space and streets, transit systems, pedestrian and bicycle planning, local politics, and natural resource protection. He cross-posts from The Northwest Urbanist and leads the Seattle Lid I-5 effort. He served on The Urbanist board from 2015 to 2018.