In yet another hit piece aimed at local government, The Suburban Seattle Times is questioning an effort to increase the efficiency of city streets. Hiding behind Briar Dudley, a technology columnist with no apparent planning credentials, the Editorial Board is lambasting an appendix in the Seattle 2035 plan for a minor policy which is intended to modify how traffic is measured on city streets. If Dudley is to be believed, it will make driving a living hell in Seattle. The reality is much more nuanced and rational.

As is tradition, the headline for the column is hyperbolic and factually inaccurate: “City’s vision for a carless Seattle doesn’t match reality”.

If Seattle were indeed planning for a carless future, that headline would be fine. A carless Seattle is utterly ridiculous and a complete fantasy. In my own writings, I have embraced the necessity of automobiles for modern civilization. But the fact is that nobody in the City government, and no one working in the transportation sector, in advocacy in Seattle, or elsewhere, is proposing such a thing. This headline is only intended to inflame a fictional debate and draw in angry readers.

And then Dudley opens his piece with: “Seattle can no longer deny it’s engaged in a war on cars.”

Let’s stop right there. Seattle, and practically every local and state government in the United States, has done nothing but bend over backward for automobiles for the past century. We’ve widened suburban roads, mandated millions upon millions of parking spaces, and ripped apart urban neighborhoods to build thousands of miles of controlled-access freeways. This country is built upon car infrastructure, and it has shaped our culture, our economy, and our politics. And it results in up to 38,000 deaths every year, four million more life-altering injuries, unbelievable amounts of pollution and carbon emissions, and a systemic marginalization of the millions of Americans who can’t or won’t drive for physical, financial, or personal reasons, including our children and the elderly.

But as soon as a local government does a little more for those people who get around in other ways, as soon as we stripe a bike lane, expand a sidewalk, install a bus signal, or charge a dollar for parking, a “war” is declared by the perceived victims who drive around $30,000, three-ton vehicles.

A war.

A battle. A siege. As if the forces of evil are descending upon the city to murder our cars and pillage our parking spots, burning every 12-foot strip of asphalt in their wake. Dudley embraces this by following up with, “…the new growth plan is a shock-and-awe campaign targeting anyone who dares to drive in, through or around Seattle.”

He explains, “Under a novel standard proposed by Murray’s transportation department, street performance will be ranked by how many single-occupant vehicles (SOV) are using them.” That’s it.

Dudley helpfully links to the 580 page draft Seattle 2035 plan, but one has to go digging to find out exactly what he’s talking about. It’s buried in the Transportation Appendix on page 437, under a section titled Local Level of Service Standards for Arterials and Transit Routes:

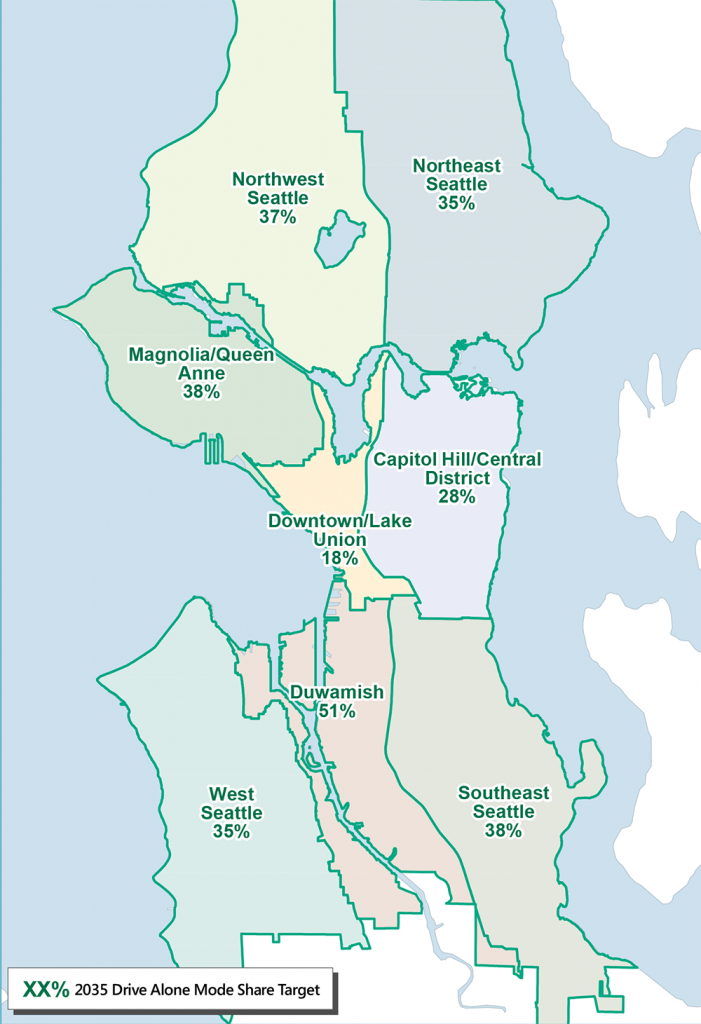

This measure focuses on increasing the people-moving capacity of the city’s roadways by reducing the SOV share of travel. The SOV share of travel is the least space-efficient mode and occurs during the most congested period of the day…These performance levels differ from the prior screenline-based system. A target SOV mode share has been established for…eight sectors of the city and will be applied to every development project.

In essence, this is indeed a novel approach to measuring the performance of local streets. The traditional Level of Service (LOS) tool ranks roadways based on how fast cars move; free flowing traffic gets an A, and gridlock gets an F. As demonstrated by over 60 years of post-WWII sprawl, the problem with this is it leads to an infinite loop of congestion, construction, and poor urban environments. Cities set a high standard for LOS, see that traffic is congested, widen roads or build new ones, see that the roads fill up with more cars due to induced demand, and repeat ad nauseam. This is also results in limited, if any, consideration for other users of the street: people walking, bicycling, and riding transit.

Seattle is not hiding the fact that it is more concerned about moving people than cars. When a City reaches a certain size it is only prudent to prioritize more people-friendly and efficient ways of moving around. Streets packed with people are a good sign of urban vitality and desirable city. Even traffic jams are a good indicator of economic health; no major city in the world has figured out how to completely get rid of vehicle congestion.

Dudley conveniently leaves out the Seattle 2035 plan’s elaboration:

Adding vehicle capacity can be costly, and can lead to community disruption and environmental impacts. In many cases, widening arterials may not even be practical or feasible in a mature, developed urban environment. This mode share method of measuring LOS allows the City to use existing current street rights-of-way as efficiently as possible…

But he does describe the concurrency principle of the Growth Management Act: “To ensure streets aren’t overloaded, cities must use level-of-service standards to grade performance. If streets fail, cities can limit development until improvements are made.”

With our rate of population growth, limiting development is not an option. And by “improvement” the vast majority of traffic engineers interpret that as “widen”. Widening Seattle’s streets is not physically possible. We have many lovely neighborhoods with buildings that sit on the edge of the property line and adjacent to the sidewalk. If Dudley is thinking along the lines of traditional LOS, we can only conclude that he is also advocating for arterial expansions that will unleash destruction on a massive scale, displacing thousands of residents and businesses, taking away hundreds of acres of private property, and purging the City’s coffers.

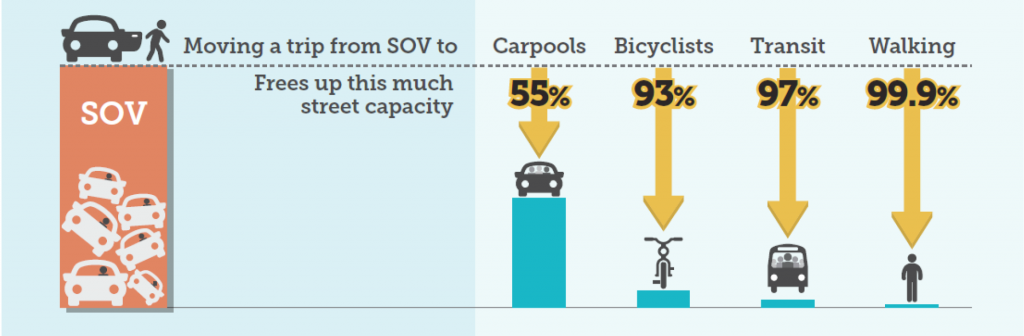

Dudley really makes a stretch when he says Seattle is ignoring state and federal transportation standards: “[The City] says single-occupant vehicles are inefficient so reducing them improves level-of-service. That’s debatable.” He’s dead wrong: there is no debate. The laws of geometry dictate that the fewer cars there are on a stretch of road, the faster those cars will go. A comparison of modal efficiency is shown above.

Many experts in the transportation planning and urban design fields have recognized the futility of LOS. In 2014, California kicked LOS to the curb for any development projects that require environmental review; instead, the state now requires calculating how much vehicle-miles-traveled (VMT) will result from a project, a much more useful gauge of how many car trips will be generated, and what the associated impacts will be on multi-modal transportation systems and the environment. Washington State should follow California’s leadership and swap VMT for LOS in development review.

All of this said, the City of Seattle is not proposing to entirely abandon traditional measures. The very same section that Dudley references contains a wealth of detail on the City’s current and projected volume-to-capacity (V/C) ratios on arterial streets around the city. The V/C ratio is related to LOS and compares the number of cars using a street to how many cars can physically fit and move reasonably quickly. Despite the anticipated reduction of vehicle capacity of a few streets due to the addition of bike lanes, over the next 20 years the City does not expect V/C ratios to significantly increase, i.e. go beyond 100 percent.

Dudley goes on to conclude that the City’s policy “gives the finger” to everyone who drives, including nearly all residents and businesses, and, without any data or citation to back it up, declares that congestion is harming Seattle’s cultural life and arts organizations because people are giving up on driving and parking in the city. The fact is that people who drive alone in Seattle are a minority.

City-level data is available on pages 71-72 of the Seattle 2035 plan. It shows 43 percent of work trips that end in Seattle are made by driving alone. But even less of Seattle residents’ nonwork trips, 33 percent, are made by driving alone. In the Center City, the numbers keep going down; 31 percent of Center City employees get to work by driving alone, and only 23 percent of employees in the Downtown core drive alone.

In a similar vein, survey data shows at least 9,000 Seattle residents have ditched car ownership thanks to car2go membership. The number is likely much higher considering the growing variety of other carshare, rideshare, and transit services in the Seattle. And it has surely relieved traffic congestion and on-street parking crunches for the people who still own cars. The number of car-free households will only grow as the city’s population grows and options for getting around improve.

Dudley concludes by lamenting, “…City Hall’s assuming that driving is optional—a lifestyle choice—and it can force people to change how they live.” What we have in Seattle and beyond is not a war on cars, Mr. Dudley. The reality is we are fighting back against a genocide of choice. Our infrastructure does not give the vast majority of Americans any other option than driving. Sharing the small percentage of streets in the densest neighborhoods with safer and more efficient infrastructure for walking, bicycling, and transit is not forcing people to do anything—it’s only giving them more options. And yes, the fact is that more people will likely take advantage of those choices when they have access to them and realize the benefits. That’s how the marketplace works, so why shouldn’t our streets work the same way?

The Seattle Times Editorial Board has always urged government to operate like a business, but then they balk when local agencies engage in business-like marketing and make more efficient use of urban resources that will inconvenience the Board and its suburban subscribers. As our region’s only major print newspaper, the Editorial Board and its individual members have a responsibility to more strictly check their impulses and conduct balanced research on the issues.

That’s what we do here at The Urbanist, and we will continue to offer deeper insight, data, and reasoning on the urban policy issues that matter the most to our growing city and region.

Scott Bonjukian has degrees in architecture and planning, and his many interests include neighborhood design, public space and streets, transit systems, pedestrian and bicycle planning, local politics, and natural resource protection. He cross-posts from The Northwest Urbanist and leads the Seattle Lid I-5 effort. He served on The Urbanist board from 2015 to 2018.