Seattle’s major comprehensive plan update is entering its final stages before final adoption mid-year. Mayor Ed Murray released his Recommended Plan last week, which covers everything from future land use and implementation policies to existing capital facilities and future infrastructural needs. The plan, known as Seattle 2035, is a whopping 580 pages in length and charts a new path for the city over the next two decades. The overall plan is similar to Alternative 4 presented in the Draft Environmental Impact Statement released last year, but with slightly lower amounts of residential growth directed to urban villages.

The importance of comprehensive plans cannot be understated. These documents are the blueprints from which almost every action that a city or agency makes is based. They also have a long shelf life, which is why Seattle’s comprehensive plan covers a nearly two decade long period. Recognizing the rapid local and regional growth, the plan anticipates increases in population (120,000 people), housing (70,000 dwelling units), and employment (115,000 jobs) through 2035. All of this growth means that specific actions must be taken to sustain it whether that is through increased sewer capacity, new police stations, or redesigned transportation facilities. Recalibrating the comprehensive plan for today’s realities and tomorrow’s future is an imperative.

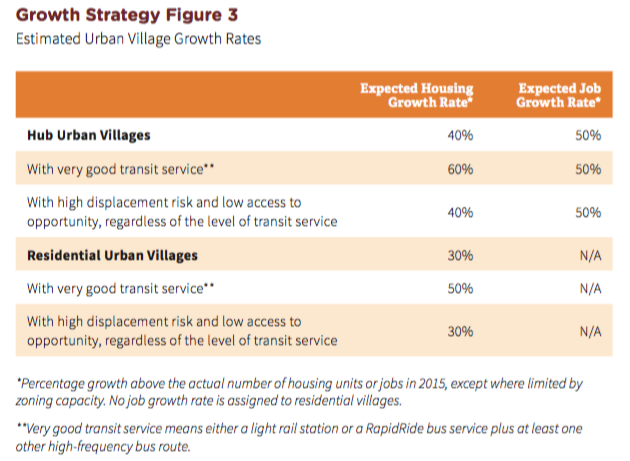

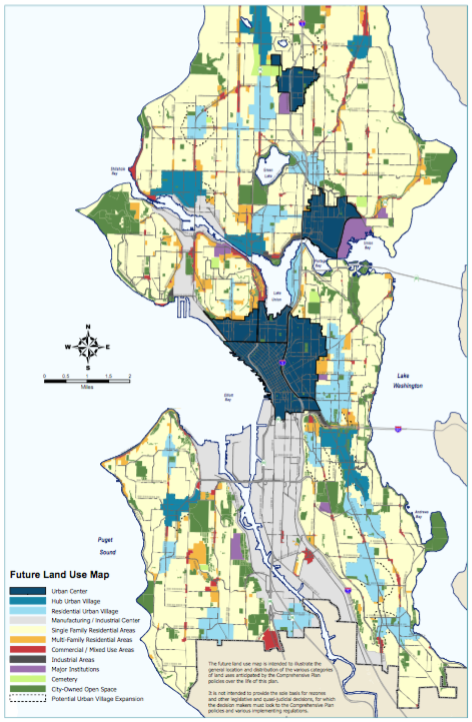

The Mayor’s plan stays true to a core planning principle called the “Urban Village Strategy”. This is a long-standing planning principle that intentionally directs most urban growth into designated urban centers and urban villages where new development can be readily serviced and accommodated. The city has two kinds of urban villages, known as “Hub Urban Villages” and “Residential Urban Villages”; the primary difference between them is that Hub Urban Villages typically are planned for higher residential densities and provide high rates of employment opportunities and services (e.g., Ballard and Fremont) whereas Residential Urban Villages are meant to achieve lesser densities and have considerably lower rates of employment (e.g., Othello and Morgan Junction). Meanwhile, Urban Centers (e.g., Downtown, University District, and Northgate) are the densest neighborhoods with the widest range of employment and service opportunities locally and regionally.

The comprehensive plan seeks to achieve five primary goals through the Urban Village Strategy. Specifically, the Urban Village Strategy:

accommodates Seattle’s expected growth in an orderly and predictable way;

strengthens existing business districts;

promotes the most efficient use of public investments, now and in the future;

encourages more walking, bicycling, and transit use; and

retains the character of less dense residential neighborhoods outside of urban villages.

It should also be noted that the Urban Village Strategy actively seeks to maintain industrial and manufacturing lands. Two areas of the city are designated as Manufacturing/Industrial Centers, which include industrial areas in Ballard/Interbay and Duwamish/SoDo.

The Mayor’s plan does make substantial changes to City policies. Brand new ideas have found their way into the plan, like how to better use streets for public space (e.g., play streets, sidewalk cafés, and parklets). The City’s goals to develop and maintain open space has been revised so that they are realistic and achievable. And to provide a concrete example of how major policies have been redesign, look no further than the Land Use Element’s section on Single Family Areas. Land Use Policy 58 currently states:

Use a range of single family zones:

- Maintain the current density and character of existing single-family areas;

- Protect areas of the lowest intensity of development that are currently in pre-dominantly single-family residential use, or that have environmental or infrastructure constraints, such as environmentally critical areas; or

- Respond to neighborhood plan policies calling for opportunities for redevelopment or infill development that maintains the single-family character of an area, but allows for a greater range of residential housing types, such as carriage houses, tandem houses, or cottages.

Compare that to the Mayor’s plan which now reads as follows:

Use a range of single-family zones to:

- Maintain the current low-height and low-bulk character of designated single-family areas;

- Protect designated single-family areas that are predominantly in single-family residential use or that have environmental or infrastructure constraints;

- Allow different densities that reflect historical development patterns; and

- Respond to neighborhood plans calling for redevelopment or infill development that maintains the single-family character of the area but also allows for a greater range of housing types.

The remolded language seeks to maintain the overall character of single-family residential areas, but offers additional flexibility over today’s plan.

They Mayor’s plan recommends expansion of ten existing urban villages and creation of a brand new one. The expansion and addition of urban villages came out of a clear direction by the public to guide future growth into areas with very high quality, frequent transit service. In tandem with this goal, a concept of designating areas within a 10-minute walkshed of high quality transit in urban villages was added. That’s why places like Roosevelt and Beacon Hill could see larger urban village boundaries. Likewise, light rail extensions to Lynnwood and Redmond will eventually deliver stops at Judkins Park and NE 130th St during the life of the plan. The Mayor recommends creating a totally new urban village around I-5 and NE 130th St and merging two urban villages around the future Judkins Park stop.

The new comprehensive plan is more accessible. A lot of the complexity, discontinuity, and jargon of past plans have been entirely cut out. Instead, the plan begins with the context in which the City is planning for and then lays out high level citywide policies and goals. These policies and goals cover core elements of a comprehensive plan like Housing, Transportation, Arts and Culture, and Shoreline Areas. The plan then zooms into the neighborhood-level with specific plans for over 30 different neighborhoods across the city. The plan wraps up with an appendix that provides key background data on population and housing, existing land use patterns, utility capacity, and public infrastructure generally. Each of these sections vary in specificity, but ultimately their relationships are very strong thanks to a clearer arrangement of the plan.

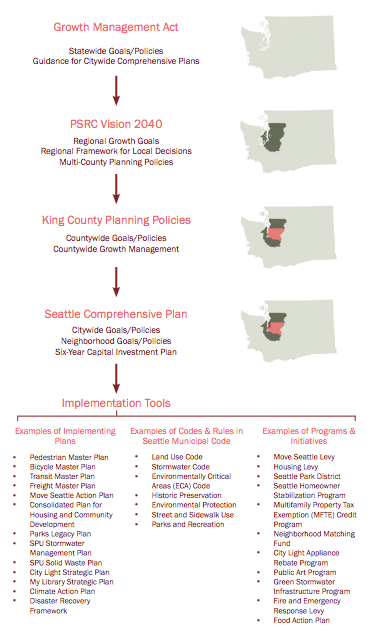

The plan isn’t one-dimensional. Comprehensive planning is about actions. Inputs drive outputs. In formulating the proposal, the City looked at the full context of Seattle and the region. Some inputs have filtered up from neighborhoods and specific programs that communities have implemented (e.g., programs from business improvement districts and neighborhood grants for special projects). Other inputs have come directly from the City like the implementation of the Seattle Bike Master Plan, Housing Levy, and Solid Waste Plan. And some inputs have come from outside of the City as part of statewide requirements and regional planning with local partners (e.g., Puget Sound Regional Council and transit agencies); examples of those include the State-mandated requirements for stormwater and Sound Transit capital investments planned or under construction. In other words, the comprehensive plan is a complex document that looks at all aspects of our built and natural environment as well as social and economic realities.

Growth doesn’t come without costs. That’s why the process has been very focused on ensuring that changes to the comprehensive plan will support equity goals. In fact, the City went to great lengths to conduct an extensive equity analysis to identify how socially disadvantage groups might be impacted by policies. The review of policy proposals found that expansion of some urban villages would generally result in a low risk of displacement. But expansion of urban villages in Othello, Columbia City, North Rainier, North Beacon Hill, and Rainier Beach all pose high risks for displacement. Specifically, the equity analysis described the displacement risk for these areas in this way:

It is not clear that expanding urban village boundaries supports the equitable development strategies outlined for these villages. New development may put upward pressure on rents before community stabilizing investments take effect. A well-resourced mitigation strategy coupled with expansion of housing choices over time could prove successful, but further community engagement and analysis should be undertaken to determine the feasibility and details of such a strategy.

The equity analysis sources a wide range of differing quantitative measures to look at topics like people of color, proximity to transit, median rent, tenancy, and more to better understand variables that affect access to opportunity and displacement. The basic takeaway from the analysis is that the City should adopt specific tools to actively mitigate and prevent displacement, particularly in areas of high risk, as a result of the City’s urban growth strategy. Ultimately, the City will continue to monitor and measure quantitative and qualitative social equity outcomes as part of the comprehensive plan.

The new comprehensive plan has been transmitted to the City Council and will be considered over the next few months. That plan should make it out committee sometime this summer and be enacted into law shortly thereafter.

Stephen is a professional urban planner in Puget Sound with a passion for sustainable, livable, and diverse cities. He is especially interested in how policies, regulations, and programs can promote positive outcomes for communities. With stints in great cities like Bellingham and Cork, Stephen currently lives in Seattle. He primarily covers land use and transportation issues and has been with The Urbanist since 2014.