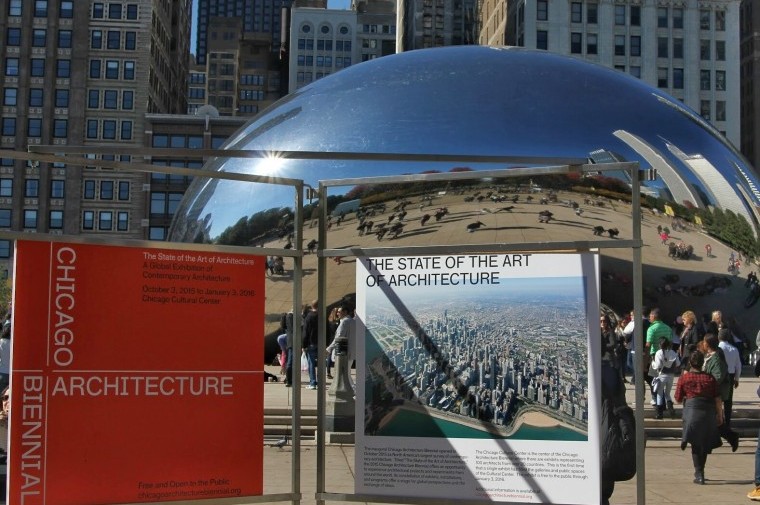

On a cold October evening in Chicago, Mario Cucinella shares his thoughts as to why architecture is of vital importance to society: “Buildings don’t move, but they travel in our memory”. As an architect who has designed buildings with sustainability and the experience of people at the core, his words are evocative of the legacy of architecture, and our unique relationships with the buildings we are surrounded by, both physically and in our imagination. This is just one of many interesting conversations facilitated by the three-month inaugural Chicago Architecture Biennial which finished in January 2016. The event reconnected Chicago with its identity as the architectural centre of the modern world, with the theme of the Biennial, The State of the Art of Architecture, prompting consideration of the experiences offered by the built environment, the longevity and adaptability of places, and the evolution of architecture in serving the needs of people. The Biennial celebrated architecture as art on the largest scale – an art form of the city, for the people.

The Biennial has been heralded as the first and largest contemporary architectural survey in North America. Chicago has a history as a powerhouse of innovative design, bringing the world the elevator and the skyscraper, and fostering many internationally renowned architects (Daniel Burnham, Louis Sullivan, Frank Lloyd Wright and Mies van der Rohe to name just a few). With an incredible array of architectural styles decorating the skyline, Chicago is a natural setting for an international event exploring the past, present and future state of architecture. Supported by $6.5 million in private funds, the co-curators of the Biennial, Sarah Herda and Joseph Grima, selected 100 participants from 30 countries to exhibit, with partner organizations delivering complementary programs across the region. The Chicago Cultural Center, a grand neo-classical building, adorned with the largest stained glass Tiffany dome in the world, served as the Biennial hub, with other installations and exhibits in public spaces and institutions across the city. Exhibits and programs ranged from the tangible to the abstract, addressing the responsibility of architects to the public and the environment.

Projects exploring housing reflected vastly different geographic and economic settings, responding to the urgent need for shelter as well as its commodification. A shared focus of many, was the importance of delivering affordable housing which minimizes the environmental footprint. Otherothers, offset the frame of large suburban homes in Sydney, creating a case study for how new semi-public space can be created. ‘Offset House’ responds to the challenging contradictions of Australia’s status as one of the most urbanized, yet low density countries, due to large home sizes. Reflecting the traditional “Australian dream”, the large scale houses are contrasted with housing projects from other parts of the world, that are confronted with a scarcity of resources and wealth. Several full scale prototypes highlight the grave global need for affordable, quick and easy to construct housing.

The ‘S House’ by Vo Trong Nghia Architects from Vietnam is a pre-fabricated steel dwelling with a 30 year life-span, which can be constructed in 3 hours for less than $1,000. The project was developed in response to the need for affordable, durable, easy to construct housing for people with an average income of less than $130 per month, and has evolved from several prototypes and is nearing mass-production. The 345 square foot house can be expanded for a growing family, or adapted for other functions, such as a school, shop, clinic or emergency facility.

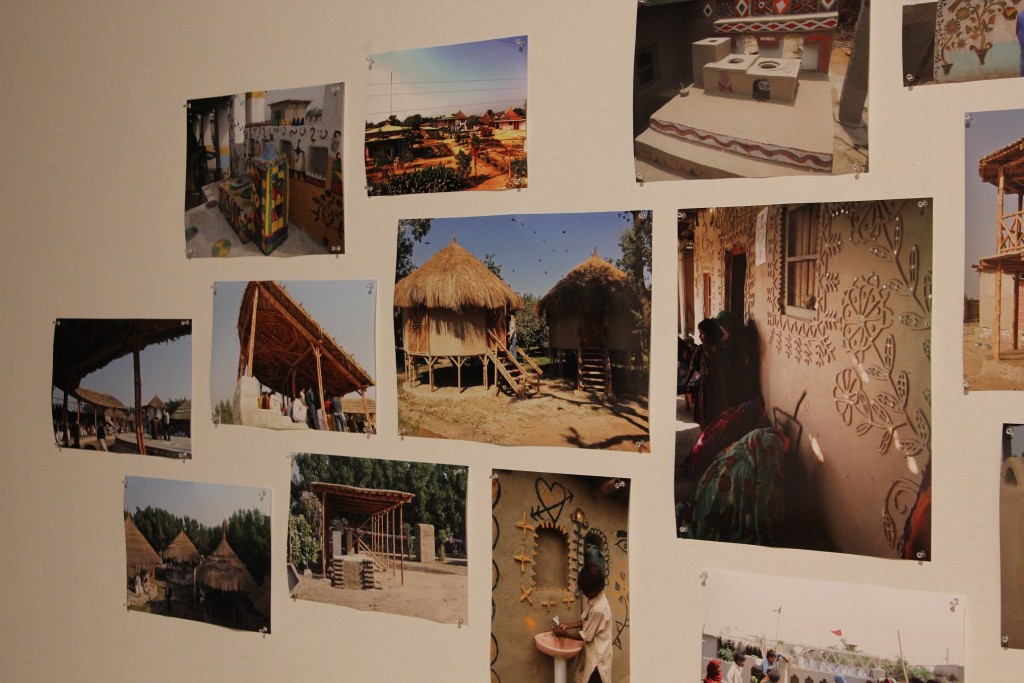

Similarly, Mexican architect Tatiana Bilbao’s ‘Sustainable Housing’ is created to be flexible, allowing residents to extend over time to suit their needs or adapt materials and layouts to suit the country’s different climates. The 463 square foot, 2 bedroom house, with a core comprising concrete blocks surrounded by wooden pallets, costs just 8,000 USD to build and responds to Mexico’s shortage of 9 million homes. ‘Barefoot Architecture’ by Yasmeen Lari and Heritage Foundation of Pakistan is a photographic display of disaster resilient housing. 40,000 of Lari’s KaravanShelters, a self-build and zero-carbon structure constructed with mud, low-energy lime and renewable bamboo, have been developed in 1,700 communities in partnership with the International Organization for Migration. These projects offer low-cost, seismic and flood-resistant solutions for disaster prone regions, and also offer potential for reducing the energy and water consumption of construction in richer countries.

In ‘180 Square Meters’, architect Jo Noero, showcases the challenging economics and inequalities of housing, with adjacent models of a 1884 square foot luxury clifftop villa and a striking 474 square foot house as part of a larger public housing project in an impoverished town in South Africa. Noero’s work highlights the disparities between housing as an often unmet human right versus a luxury or commodity. The architect uses commissions for the wealthy to subsidize housing projects for low-income people, limiting the size of private commissions to approximately 1938 square feet, as a maximum living space necessary for a family. The project aptly turns attention to the power of architecture in redressing inequalities.

The program demonstrated the immense responsibility architects have to the public to use their art to improve social equity, environmental and health outcomes. Many of the Biennial projects responded to the opportunity to use design to improve quality of life at the community or city scale, with many of these focusing on Chicago. Amanda William’s ‘Color(ed) Theory’ drew attention to abandoned houses in Chicago’s South Side, with these overlooked buildings painted vibrantly prior to their demolition. The process prompted people to reconsider the value of places and question the coded meanings of colour, asking which represents gentrification, poverty or privilege.

Another Chicago-based project by Jeanne Gang, illuminated the relationships between police and the community, offering ideas to foster these by creating stations as community hubs. ‘BOLD: Alternative Scenarios for Chicago‘, curated by Iker Gil, featured 18 projects by different designers exploring various challenges, solutions and futures, intended to spark animated discussion about what Chicagoans want and need of their city.

Port Urbanism’s vision encompassed 225 acres of land to be added to Lake Michigan to enable new skyscrapers to the east of Grant Park. The dense development is intended to contribute much-needed municipal tax revenue, as well as create new lakefront parkland. In contrast, UrbanLab proposed an island on Lake Michigan to revitalise nature and reverse the flow of the Chicago River to its historic state. The island park would filter and clean polluted wastewater before it enters the lake. The diverse projects point out opportunities to rethink the way we value and design our communities, and create new blueprints for our cities which blend the territories of public and private, built and natural.

The Biennial extended into many of Chicago’s public spaces, cultural institutions, businesses, and universities, perhaps mirroring the sentiment of Sou Fujimoto Architects’ exhibit that “Architecture is Everywhere”. The clever (and sometimes comical) display of everyday objects (from staples to potato chips), as spatial entities inhabited by tiny plastic human figures, highlights how architecture is found and made. In a similar manner, the Biennial finds, reinterprets and creates new architectural experiences in different spaces in the city. Installations, as part of the Lakefront Kiosk competition, located beside Cloud Gate in Millennium Park, invited visitors to interact and inhabit the park in new ways.

Summer Vault was designed as a geometric hangout space to foster simultaneous commerce and community activity. ROCK consisted of limestone pieces, historically used to protect Chicago’s shoreline, in which the public is invited to shape and transform the material, prior to its integration into a pavilion at Montrose Beach in Spring 2016. The kiosk will incorporate materials and technologies from the local environment, and will leave a remnant of the inaugural Biennial on the city.

Through the Biennial, the city has gone to great efforts to put architecture at the forefront, reflecting the aspiration to reinforce the rich heritage as an epicenter for innovation in architecture, engineering and city planning. The Biennial continues the architectural legacy of former Mayor, Richard M. Daley, one of the first major city mayors in the USA to promote sustainable development. In the 1990s, Daley campaigned to make Chicago one of the greenest cities in the country through sustainable building design and the expansion of greenspaces. Like his predecessor, Mayor Rahm Emanuel seeks to use architecture, as well as the Biennial “to brand the city as the place, as it has always been, of modern architecture“.

Despite the state of the city’s finances, Chicago has continued to invest in architecture. The Chinatown branch of the Chicago Public Library was recently opened, art is being integrated into rapid transit stations and along the lakefront, and the Chicago Riverwalk is being redeveloped to enhance pedestrian access. Such endeavors elevate the design of public spaces and assets. Chicago isn’t just concerned with great buildings and places being delivered, but also placing the city at the “dead centre” of conversations about architectural ideas, a vision which has begun to be realized through the Biennial. As articulated in the Chicago Tribune, “good design is a key instrument in the mayoral toolbox. And it has symbolic power“.

The Biennial is a milestone, both for Chicago and the USA, enabling a diversity of designers from across the world to explore and discuss the future of architecture. The Biennial attracted double as many visitors as the Venice Architecture Biennale and created a platform for people to engage with pressing challenges affecting our habitats. At the Tuesday evening discussion, Mario Cucinella aptly describes how a building is the first level of education, with its inhabitants offered the opportunity to learn about the local environment, sustainability, and social equity. Given the profound impact that architecture has on our lives and memories, Chicago is demonstrating a commitment to generating public conversations about its future, with the next Biennial scheduled for 2017.

Sarah is an urban planner and artist from Melbourne Australia, currently living in Seattle. She has contributed to diverse long-term projects addressing housing, transportation, community facilities, heritage and public spaces with extensive consultation with communities and other stakeholders. Her articles for The Urbanist focus on her passion for the design of sustainable, inviting and inclusive places, drawing on her research and experiences around the world.