Standing along side affordable housing advocates yesterday, Mayor Ed Murray unveiled his latest legislative proposal to tackle rising housing costs that are pushing lower income residents out of Seattle. In sum, the proposal would create new requirements for most multi-family residential development to set aside a certain percentage of units as affordable housing. This legislation will form an integral piece of the Mayor’s affordable housing framework, known as the Housing Affordability and Livability Agenda (HALA), by helping to directly contribute toward the larger goal of creating 6,000 new affordable housing units over the next 10 years. The HALA framework itself is built upon a subset of far reaching policy objectives ranging from enhanced tenant protections and backyard cottage reform to the adoption of a new Housing Levy and changes to state law.

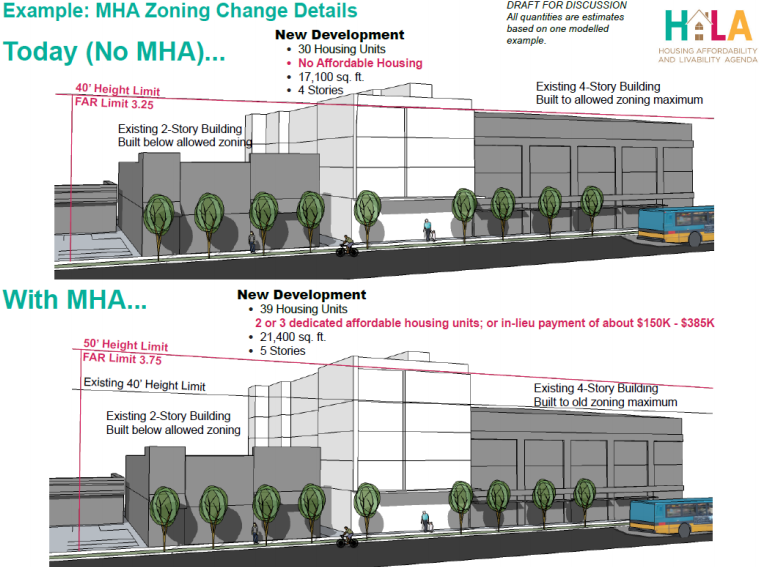

Late last year, the City adopted a similar affordable housing proposal to the one that the Mayor is now seeking, except in that case it was to require affordable housing to be set aside for new commercial development. The two affordable housing policies are meant to work in concert with each other as a complete toolkit: one as Mandatory Housing Affordability-Commercial (MHA-C), the other as Mandatory Housing Affordability-Residential (MHA-R). Once both toolkits are formally established, the City can begin to unlock their fruits in phases. Both policies are predicated on giving additional value to developers in exchange for guaranteed affordable housing units. The City plans to use additional development capacity (i.e., rezones), typically through the additional allowance of one to two stories of floor area, as a carrot to bring developers onboard with the policy framework.

How It Will Work

The proposal has a few key aspects to it, and they’re important to understand. Firstly, the legislation will be applicable to new residential development only, specifically in areas of the city where development capacity has been increased. That means that a piece of property is only subject to the requirements of the legislation if a rezone would result in the allowance of additional residential development capacity. Assuming that has occurred, new development would only be captured by the MHA-R requirements if new residential units would be added.

Secondly, developers will have flexibility in deciding how to provide MHA-R units. A developer could construct affordable housing units on-site (performance option) as part of their project or pay a fee in-lieu (payment option) to the City so as to fund the acquisition of affordable housing. Assuming a developer proposes affordable housing on-site, they will have two options: rental units or ownership units. In both cases, the units must be affordable to tenants for at least 50 years; the only difference is the targeted area median income (AMI) requirement.

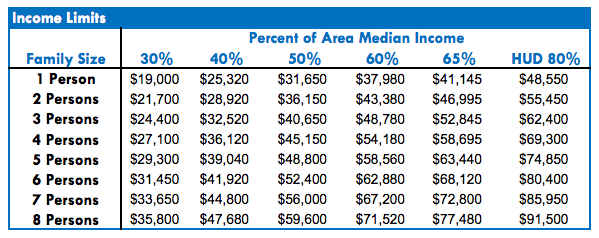

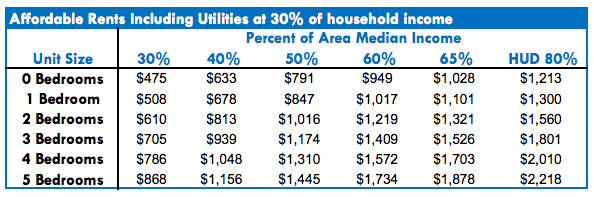

Affordable rental units will be required to serve households with incomes no more than 60% of the AMI while affordable ownership units will be required to serve households with incomes no more than 80% of the AMI. If a developer chooses to forego on-site affordable housing, then they’ll automatically be subject to the payment option. Any fees collected for affordable housing will be used to produce or preserve affordable rental units with a target to serve renters at 60% of the AMI or less.

For context of how AMI plays into all of this, the Office of Housing has a handy set of tables that outline the income limits for individuals and families as well as the maximum rent for affordable units:

It’s also worth bearing in mind that the average rent for new market rate units ranges between $1,399 and $1,887 per month. Individuals and families that would be able to partake in the affordable housing program will get the benefit of quality units entering the housing market at substantially reduced rates.

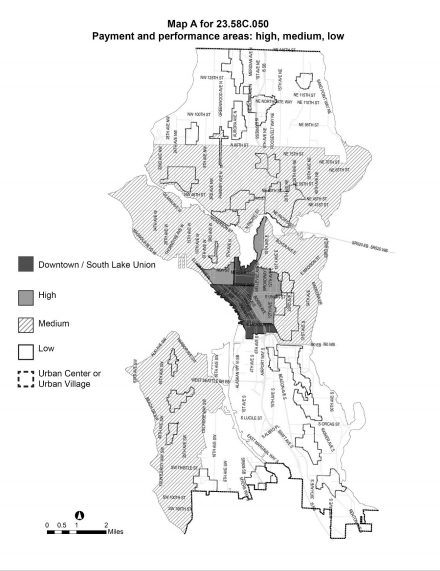

Thirdly, the amount of affordable housing that would be required from residential development will differ by area of the city. Developers choosing to provide on-site affordable units could be required to provide between 5% and 8% of their units as affordable, depending upon the location. A commensurate amount of units could be paid for by fee if the developer elects to forego the provision of on-site units.

Fourthly, the legislation will be applicable to more than just what one might ordinarily think of as new development. Developers will be required to participate in MHA-R whenever:

- A new structure with residential units is constructed;

- An alteration of an existing building would result in net new residential units (e.g., adding basement units to an apartment);

- A change of use would add new residential units (e.g., converting commercial space to residential units); and

- An addition to an existing structure would add new residential units.

Fifthly, developers that choose to participate in the on-site affordable housing performance option will have to abide by strict rules on the quality of housing. In essence, affordable housing units will have to be comparable to other units in the development. That means that the status of the affordable housing units (live-work, congregate, or standard apartment/condo) will need to be functionally the same with regards to square footage, number and size of bedrooms and bathrooms, unit amenities, access to building amenities, and the term of lease.

And sixthly, the legislation makes it clear that any affordable units created through the MHA-R program cannot benefit from public subsidy (e.g., the Multifamily Tax Exemption program). The obvious reason here is that the City doesn’t want developers to double dip from added development bonuses and public expenditure on social welfare. Instead, developers have an obligation to first meet their affordable housing requirements and secondarily can assign additional units for separate housing subsidy programs.

Baked into the legislation is monitoring and fail safes. The Seattle Department of Construction and Inspections will be responsible for monitoring implementation of the MHA program and delivery on the goal for 6,000 affordable housing units by 2026. The first MHA report is due by the end of the second quarter in 2018 and thence annually by July 1st. The primary purpose of this is to determine the effectiveness of the program and if additional amendments to the ordinance are necessary. Four circumstances are laid out in which the Council could consider amending the ordinance:

- The program fails to meet the expectations for performance in the first five years;

- There are major positive or negative changes to the real estate market for development;

- There is a need to adjust the amounts required for the payment or performance options; or

- If none above circumstances are applicable, then the ordinance could be amended generally after 10 years.

Policy Timeline

With the introduction of the legislation to Council, the timeline for review, deliberations, and adoption is targeted to be short. The Planning, Land Use, and Zoning Committee will take up the proposal on Tuesday (May 3rd) for the first time and a second committee review is planned again in early June. The Mayor anticipates that the legislation could make it out of committee by mid-July and end up on the full council consent agenda for July 25th. Once approved, the MHA-R will complete the MHA framework and allow the Council to pivot to legislation concerning rezones that will help implement MHA.

In fact, the first set of rezones that could find approval by the Council are expected this summer. The University District Urban Design Framework has been waiting in the wings for nearly a year and will likely kick off the slate of rezones immediately after the adoption of MHA-R. Rezones on 23rd Avenue could also be approved in fall, but the biggest set of rezones — area-wide/zone-wide rezones — will wait until a more robust series of discussion in 2017. Under the HALA framework, those are expected to come in the Summer 2017/Fall 2017 timeframe.

Stephen is a professional urban planner in Puget Sound with a passion for sustainable, livable, and diverse cities. He is especially interested in how policies, regulations, and programs can promote positive outcomes for communities. With stints in great cities like Bellingham and Cork, Stephen currently lives in Seattle. He primarily covers land use and transportation issues and has been with The Urbanist since 2014.