On Saturday morning, residents of northeast and central Seattle woke up to find dozens of bus routes reoriented. These changes were negotiated, advocated for, protested against, and screamed about for the past 18 months. With the introduction of two light rail stations that have drastically cut travel times in the corridor, Metro engaged in a long public process to find out just exactly how it might be able to best serve the new stations while still maintaining high service levels for existing riders. Results were decidedly mixed.

Northeast Seattle: The Weekend Wasteland

In northeast Seattle, a new network will be formed that relies for the most part on University of Washington station to do the heavy lifting between the University and downtown, and in the process those service hours saved will allow Metro to provide frequent service to areas that it didn’t previously. There are some very notable holes in the new northeast network: probably most notably the span of service during off peak hours, particularly on Sundays. The 71 and 73, which should provide all day feeder service to the light rail station that operates 18-20 hours per day, goes on its first run later and ends its last run earlier than it did before. This is not the model of a good revenue-neutral frequent network. But Metro has the workings of a good frequent network around the University with a little effort.

Madison Park Sinks The Capitol Hill Restructure

On Capitol Hill, the story was very different. The first proposal for a restructure proposed replacing a number of Downtown-bound routes with crosstown service. An all-day route connecting Capitol Hill Station directly to the Rainier Valley? Check. Routing the 49 via First Hill to directly connect residents there with either station? Check. 10-minute midday frequency on workhorse routes like the 48? Check. But the house of cards fell, all because of one change that Metro was banking on to make all of this happen. Merging the 11 and the 8 together to provide a frequent crosstown route that doesn’t go Downtown. Where that went wrong was the fact that Metro was trading a one-seat ride for Madison Park residents for the notoriously unreliable stuck-on-Denny 8.

This week Charles Mudede at The Stranger quoted the assisting secretary of the Seattle Transit Rider’s Union, Beau Morton, on the difference between riding King County Metro buses and Sound Transit light rail. “The buses have circuitous routes and will be slower.”

Getting Low-Income Transfers Right

The main beef that the Transit Rider’s Union has is with the incompatibility between Metro’s low-income bus tickets, sold to social service agencies who pay a fraction of the face value, and Sound Transit’s similar program for light rail trains. Reconciling these programs is an achievable goal and a laudable thing for the Transit Rider’s Union to advocate for. But I was struck by the remark by the union’s officer that seemed to suggest that buses are qualitatively inferior to light rail, especially because I was not able to find any instances of the Transit Rider’s Union advocating for any of the alternatives presented by Metro as part of the ULink restructure proposal.

Serving The Highest Need Riders

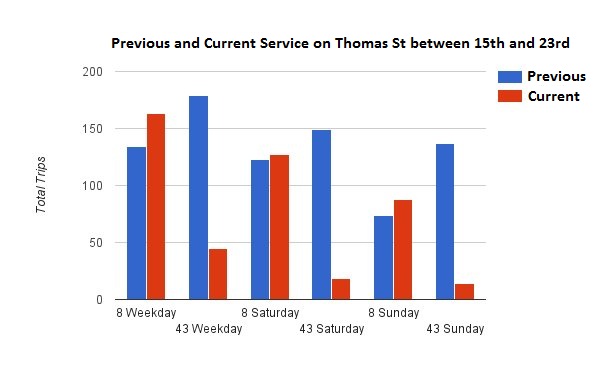

One of the outcomes of the bartering over Madison Valley bus service was that there is now a hole in the frequent transit network on Capitol Hill on Thomas Street between 15th Avenue and 23rd Avenue. This area is only served now, after the restructure, by the route 8 during off-peak times. (I don’t count the random 43’s you can ride halfway back to base; this isn’t service — it’s hitchhiking) The 8, as I mentioned, is notoriously unreliable. Previously, riders in this corridor would have had a ride to Capitol Hill Station every 15 minutes or better at most times of day.

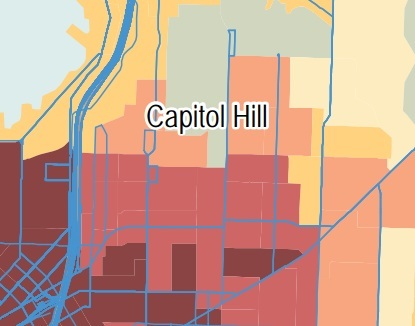

In Seattle’s Transit Master Plan, there is a map which shows the areas of Seattle which are the most transit dependent; those who lack access to a private car to get around. Madison Park, as you might expect, is not transit-dependent. The area currently left in Metro’s service hole in Capitol Hill is one of the darkest areas on the map. Madison Park was clearly able to leverage their political power to retain service; who will advocate for the transit dependent areas so that they do not lose service in return?

The next major chance that central Seattle residents will have a say in the major reorientation of bus routes in their neighborhood will likely coincide with the implementation of Madison BRT in 2019. With the dedicated lanes that this project will provide, frequent and reliable connections should be more accessible to neighborhood residents. But it won’t be an easy fight. Advocates for transit riders should learn from their mistakes in order to not repeat them.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.