Proponents of a Spokane “community bill of rights” lost their case on appeal to the Washington State Supreme Court earlier this month. Backers of the proposal had sought to place a local initiative (called Envision Spokane) on the ballot to protect the interests of Spokane residents. The initiative would have created four specific community rights by:

- Handing final decision-making on “major” developments to neighborhood voters;

- Recognizing the Spokane River as a special entity with unique rights;

- Endowing all employees within Spokane special protections against their employers; and

- Removing the rights of any corporation that violated the rights promised by the initiative.

The crux of the case hinged on whether the initiative exceeded the powers of local initiative and if certain parties would be harmed by the law if it came into force.

While all four components of the proposed community bill of rights are genuinely unique proposals, it is the first element that is particularly striking from a land use perspective.

Neighborhood Land Use Control

Under the first section of the initiative, broad powers would have been granted to local voters in neighborhoods where a zoning change might be proposed (excerpt follows, emphasis mine):

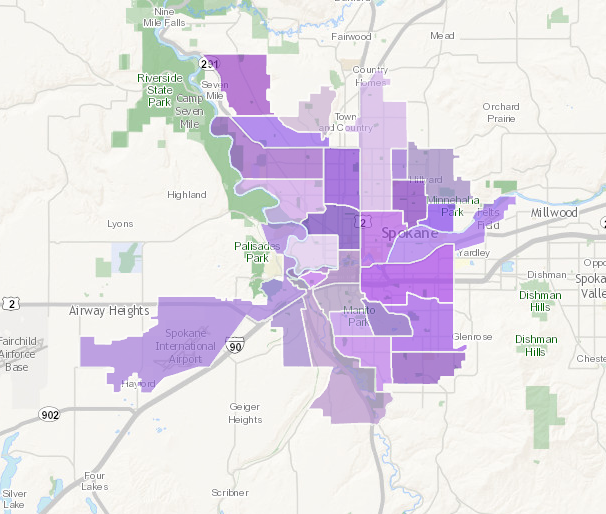

Neighborhood majorities shall have the right to approve all zoning changes proposed for their neighborhood involving major commercial, industrial, or residential development. Neighborhood majorities shall mean the majority of registered voters residing in an official city neighborhood who voted in the last general election. Proposed commercial or industrial development shall be deemed major if it exceeds ten thousand square feet, and proposed residential development shall be deemed major if it exceeds twenty units and its construction is not financed by governmental funds allocated for low-income housing.

This first paragraph of the section primarily sets out to identify the types of developments that local voters would have a say on. Commercial, industrial, and residential uses are each targeted by the provisions. Any commercial or industrial development that would exceed 10,000 square feet in size would have been subject to voter approval. Residential projects that exceeded 20 dwelling units also would have fallen under the purview of local voters, except where government-backed low-income housing were proposed. Putting this in perspective, this would essentially capture very modest development types like very small grocery stores and other retail uses, small multi-family residential projects, and additions/expansions to a range of pre-existing developments. The vagueness of the terminology could also have included neighborhood public facilities like libraries and community centers.

The second and third paragraphs of the section went on to enumerate how approval of a major project would be achieved. Applicants of a proposal would have had to actively seek the approval of local residents in a form similar to an initiative or referendum petition. While the initiative set the bar for passage of a proposal at a simple majority in favor, applicants would have had to ensure that an equal or greater number of voters who voted in the previous general election turned out to vote on the proposal. The first paragraph did restrict the geographic area in which an applicant would have to seek voter approval. Only voters in an official city neighborhood where a project were proposed would be entitled to vote on the measure.

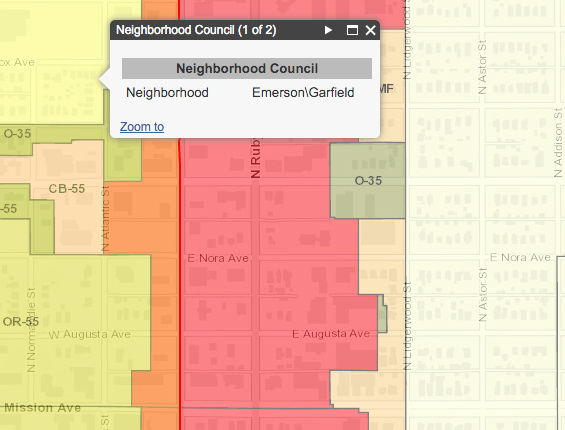

The provisions as written are obviously a high bar for applicants. For instance, the Emerson/Garfield Neighborhood has 9,4421 residents. Assuming that only 50% of residents are registered — which would be low by Washington standards — and only 70% of those turned out during a Presidential election, an applicant would need to get more than 3,300 residents to vote on the measure following that election. Of those, at least 1,653 signatures giving approval of the project would be needed. That’s no small burden.

But the provisions are also blunt. It seems entirely plausible that a development proposal could be located at the edge of a neighborhood boundary where one neighborhood has a say and another doesn’t. Take Emerson/Garfield again as an example where a vacant lot is located at the corner of Division and Indiana. Development at this location would only need the approval of residents of the Emerson/Garfield Neighborhood despite the Logan Neighborhood being directly across the street. If the purpose of the rights is to give approval powers to neighbors who will like be affected by land use changes, why use an official neighborhood geographic area as the tool?

The Supreme Court’s Decision

Courts in Washington State generally refuse to hear cases that involve initiatives prior to an election. When they do, they typically deal with procedural aspects of an initiative like the sufficiency of signatures or ballot title. Courts may also hear cases when they are alleged to be out of the legislative authority of local residents. This case falls under the latter instance. A broad set of petitioners brought suit against the initiative in 2013, including: Spokane County, The Spokane Building Owners and Managers Association, Pearson Packaging Systems, The Spokane Home Builders Association, Downtown Spokane Partnership, and many others.

Both the lower court and the Supreme Court found that the plaintiffs had standing to bring the suit against the initiative because they could be harmed by it being enacted into law. For instance, home builders and property managers could have faced impossible prospects of getting project approval for relatively minor developments let alone large-scale ones.

Ultimately, the Supreme Court affirmed the lower court’s finding that the “initiative was outside the scope of the initiative power.” The Court cited a variety of reasons for this. The first reason is that land use approval is an administrative matter that is reserved as a power of local authorities. Administrative matters may not be subject to an initiative or referendum since local authorities exercise established law or policy (e.g., administrative approval by bureaucrats, quasi-judicial approval by a judge, or legislative approval by a council). The second reason is that creating local water rights for a waterbody such as those proposed would conflict with established federal and state law. While a local jurisdiction may further regulate a waterbody, it can only do so to the degree that it does not exceed its reserved authority. Preempting the water rights of others, which are established by the state, is a clear violation of this principle. The third and fourth reasons dealt with how expanding employee protections and stripping the rights of corporations would be a violation of federal law.

While the initiative may have been well-intentioned, it would have had a dramatic effect upon development if it had been enacted into law. There’s little doubt that medium- and large-scale development projects would have ended up in even more contentious review processes and required substantial if not impossible negotiations with neighborhood residents. For even the most veteran developer or property owner, development in Spokane would be decidedly uncertain and undesirable.

Footnotes

- This number is derived from the 2010 Census for the neighborhood as provided by the City of Spokane. ^

Stephen is a professional urban planner in Puget Sound with a passion for sustainable, livable, and diverse cities. He is especially interested in how policies, regulations, and programs can promote positive outcomes for communities. With stints in great cities like Bellingham and Cork, Stephen currently lives in Seattle. He primarily covers land use and transportation issues and has been with The Urbanist since 2014.