In a recent article, I wrote about homelessness and mentioned that the building boom of new (mostly luxury) apartments hasn’t positively affected One Night Count numbers yet. Apparently, this is contentious. Urbanists are supposed to only celebrate the primal economic forces of supply and demand; critiquing the market is grounds for excommunication.

I’m not ready to concede the point however because it seems doubtful that the free market can address the needs of low-income Seattleites without being prodded to do so by the government. That’s what HALA seeks to do. Development-friendly rezones are paired with a commercial linkages fee and mandatory inclusionary zoning in order to ensure the next wave of development includes affordable housing. Time will tell if HALA is fully implemented and if the policies are sufficient to reduce homelessness and ensure that Seattle grows as a city for people of all incomes, not just the wealthy.

The lack of affordable housing is a root cause of homelessness. To assume the market alone can solve homelessness — and the twin problem of the housing shortage in the low rent market — through supply has never been demonstrated in the real world. It’s a nice theory — a good topic for an Ayn Rand book. If it were that simple.

Rent Burden

A heavily rent-burdened working class means every year more people lose their housing and slip into homelessness, rapidly replacing the lucky few that claw themselves out of it. Based on 2013 Census data, 20% of Seattle renters are severely rent-burdened, meaning more than 50% of their income is spent on rent and utilities. The volatile combination of stagnating wages and soaring housing costs has led to an explosion in homelessness in Seattle and in cities across the country.

It should be noted that the percentage of rent-burdened tenants in Seattle has been trending down from a high of 26% in 2005. Gene Balk offered this explanation in a Seattle Times piece:

With that sharp decline, Seattle now has the smallest percentage of severely rent-burdened households among major U.S. cities. That may sound counterintuitive, considering the skyrocketing rents here. But it’s more than likely that those high rents are actually the explanation: As the city becomes increasingly expensive, the most vulnerable renters are being priced out. They’re leaving — hence, the declining numbers.

Gene Balk might not see any problem with low-income tenants, many of them minorities, relocating to the suburbs: “[I]f you’re forking over half your income in rent, leaving could be your best option. There are places a lot cheaper to live outside the city.” However, it’s not clear that the tenants themselves feel that way. One drawback of suburban housing is that it often comes with a longer commute. If a tenant is able to go without a car in the city but needs to buy one to get around the suburbs, then the savings in housing costs are going to be canceled out by increased transportation costs. That’s why Balk’s solution of ‘let them move to the suburbs’ may not work well for some renters. Plus, it might lead to Seattle becoming an even whiter city than it’s already is. Seattle has an image of itself as a progressive pluralistic utopia. It’s increasingly turning into a wealthy white enclave.

Filtering: Not Much Help For Low-Income Renters

Supply-side economists rely on filtering to explain how new construction — which focuses on luxury units — helps create more affordable units in the low end. Building high-end units keeps high-income people from bidding up the prices of mid-range units. In the longer term, new units age; their relative value decreases, and they could filter into mid-range market, easing the housing pressure in that price range. The question is: do mid-range units filter into affordable low-end housing? If so, do enough filter down to take place of the low-end housing lost to be redevelopment for high-end housing? The data — rapidly rising rents and homelessness rates — suggests filtering isn’t sufficient to take care of the housing crisis, at least at our current rate of supply growth.

If Seattle existed in a vacuum, filtering would work better. The demand would be more stable, and aging units would have the time to filter down to low-income renters. However, the reality is that Seattle’s population is growing rapidly at all income levels; tens of thousands are migrating from other cities seeking jobs in the booming economy. Demand for Seattle housing is so high that supply has a hard time keeping up.

Even in a booming economy with sky-high demand, developers are extremely careful to avoid oversupply. We saw Puget Sound Business Journal sound the alarm bells at the end of 2015 when the luxury market fundamentals lagged ever so slightly. Generally, supply rarely outstrips demand too significantly except when demand plummets unexpectedly, such as during an economic recession. Even when recession hits, developers adjust quickly and bail on the projects they have in the pipeline since they fear they will not garner the rents they want. The Civic Square tower might be standing today if the 2008 recession had not hit, drying up financing and stalling the project.

Zoning Isn’t The Only Thing Constraining The Housing Market

Seattle is a supply-constrained market. Some libertarians have suggested zoning restrictions are the only thing constraining the supply, but that’s not necessarily true. Easing zoning restrictions is certainly part of the solution, but it’s a necessary but not sufficient condition for affordable housing.

Seattle is but 84 square miles. Even with liberalized zoning, land and physics eventually will become nearly as constraining as zoning is now. We have the ability to build super tall, but to do so is extremely expensive. Supertall skyscrapers are suited for luxury units, but ill-suited for affordable units since low rents cannot cover the high costs of engineering a supertall building. Large projects also need to prove they are a safe investment to the banks and investors financing them, and serving poor tenants rarely fits the bill. In the condo market, strict laws demanding a very high quality product and making it very easy to sue cause it to be challenging to serving the low- and middle-income markets where the profit margins can be tighter.

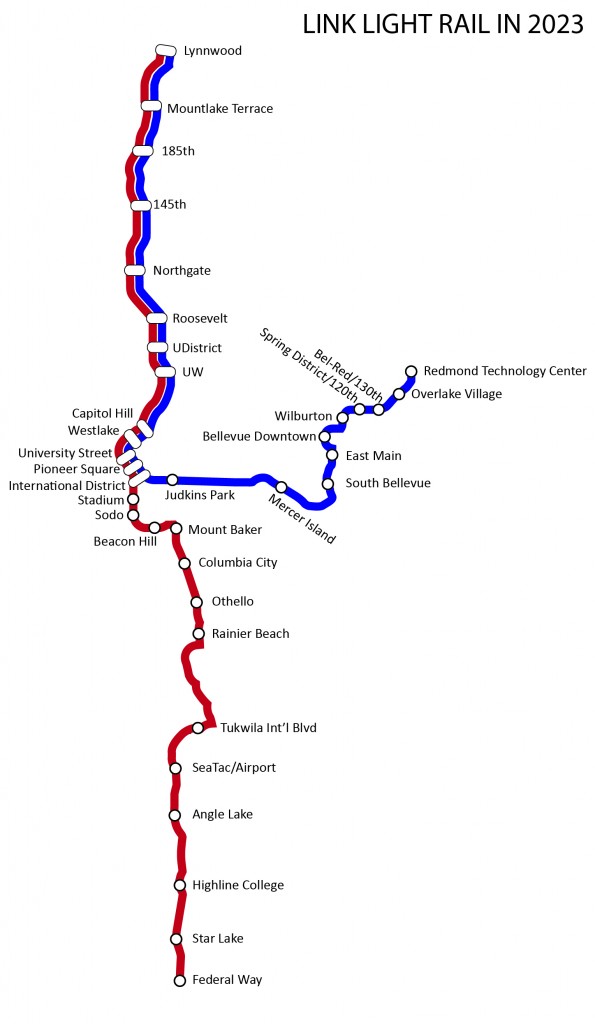

Land needs could also be met by the Seattle suburbs. Unfortunately, the transit network is weaker in the suburbs. To be well suited for dense mixed-use development, the suburbs need high capacity transit. Sound Transit is building it to select suburban neighborhoods thanks to North Link, South Link, and East Link, but it seems doubtful these three light rail lines will open up enough suburban real estate to dense mixed-income development to turn the tide.

To compound matters, the current political reality — which isn’t great in Seattle — is even worse in many suburbs where the loudest voices are dead set against multi-family development. Mercer Island, for example, nearly passed a moratorium on all residential development in December, avoiding that fate by one vote. There are some shining exceptions to this trend, but the embrace of dense transit-oriented development will have to be wide-scale enough to appreciably ease the housing pressure in the wider market for urban housing in the Seattle metropolitan area.

How To Keep The Invisible Hand From Choking Us

We need to build more housing supply. Pointing out the limitations of the market is not to argue against more supply. Even if filtering isn’t happening sufficiently, we still need to keep up a healthy growth rate or high-income people will move into lower markets and displacement will get even worse. In addition to making zoning and land use changes that encourage housing growth, the government must tilt the scales toward affordable housing with interventions like mandatory inclusionary zoning and the commercial linkage fee.

Some market urbanists opposed the commercial linkage fee for being “anti-development;” however, the fee is modest in the scheme of multi-million dollar commercial development and well worth the added zoning capacity to which it is linked. Market interventions like the linkage fee are key to guaranteeing HALA boosts of affordable housing. More market-rate supply alone might not be a huge help to people below the area median income, especially in the short term. Filtering takes time to work; low-income folks don’t have the luxury of time.

Emphasizing interventions could be crucial in convincing skeptics that liberalized zoning won’t lead to the tear down of more old affordable units than are replaced with HALA programs. Saying the solution has to be not just supply, but supply and market interventions may get me kicked out of some urbanist circles, but it’s a better policy.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.