There’s so much police, fire, and medical sprawled out everywhere you’d think it was the parking lot at Bellevue Psychiatric. This place looks like Willowbrook State in the eighties. The intersection is blocked at East Pine and Belmont, and we’re not going anywhere fast. “Looks like we’re gonna maybe be hangin’ out here for a second,” I inform the passengers, adding that this might be their best stop if they’d wanted Broadway up ahead. Parking brake with all doors open, heat turned up.

I like standing up, going for walks, especially after lots of sitting, and given we’ll be stuck for a while I step out of the bus and do so. I have a mild inclination to ask for a timeline from one of the officers on scene, that I might update my passengers, but they’re distracted and busy. I’ll do that later. For now I’m going to enjoy the night sky, and the rare pleasure of ambling around in the center of a blocked intersection.

There’s another 49 on the other side of the street, stalled as well. Still in the middle of the road, I amble over to the driver’s side, and Jeremiah opens his operator window. We shake hands and talk cameras and photography. We chat it up as if we’re in a hallway at someone’s birthday party. Nevermind all the chaos surrounding; he has a film camera he’s thinking about giving away, and we’re absorbed in discussion about bodies and lenses, the value of developing passions in life.

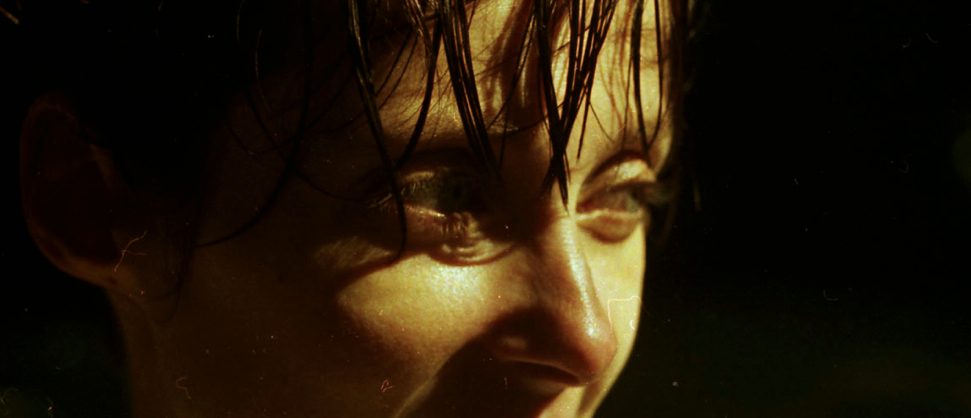

Then I notice a girl noticing me. “Listen Jeremiah, it was good talking,” I say as I bid him farewell. She’s sucking on a 4th of July pop, the patriotic colors glowing from the swirling blue and red police strobes. Blue eyes and thin, pale, that scattershot gaze which takes in everything; wavy hair and skin wrapped tightly around shapely cheekbones, that easy beauty the youth don’t know how lucky they are to have. She’s made up tonight, hint of a sparkle on her lashes, lips twinkling in the streetlight. She avoids eye contact, downcast, a wounded animal hiding behind the breezy exterior. That’s Zoë.*

“Zoë, hey!”

“Hey!”

“Gimme a hug!”

“Hey, whats goin’ on over there?”

“I dunno. Must be somethin big, this type a response.” There’s a cocktail of Fire, Medic One, four Seattle Police trucks, with a King County Sheriff or two thrown in for appearances.

“Yeah.”

I’m not that interested in calamitous details, though. I turn to her. “How are you?”

“Good. I saved someone’s life today.” Imagine her voice, husky but spry, riding the cusp between adolescent insouciance and genuine ardor. At some point in each of our lives we discover it’s okay to be passionate about things.

“No way!” I exclaimed.

“Yeah, down by the convention center, this lady was overdosing and I was just walking by and I saw her and I gave her Narcan.”**

“Oh my goodness,”

“Nobody was around, she was on the ground, and I hit her with the Narcan. It was fuckin’ awesome, well not awesome, but you know,”

She’s trying to sound cool and collected about it, but I’m totally blowing her cover with my enthusiasm. We balance each other out. “Oh yeah! Zoë, you’re amazing! Saving people’s lives! I’m so glad you just happened to be right where she was over there.”

“And I just happened to have the Narcan too,”

“So crazy. You saved a life!”

A passenger strolls over. He’d said he’d go talk to the cops, ask them to move; their cars were only inches away from not blocking everything.

“Hey,” he says to Zoë. I’m invisible to him, with her standing around. “I thought he was the bus driver.”

Zoë: “he is.”

Me: “how’s it going? What’d they say?”

“Just some drunk guy, really high.”

“Oh my goodness, that’s it? Thanks for talkin’ to them. I get kind of intimidated when there’s a bunch of ’em.”

Zoë smiles.

“Not really my crowd!”

“They said they’d be outta here any second,” he says. “Oh, there they go.”

“Right on. Sweet, let’s do this. Thanks for talkin’ to ’em.”

“Yeah.”

She and I, walking back to the bus, life around us curving back to normal.

“How are you, how’s Northgate?” I’m returning to an earlier conversation. She’s one of those street faces I encounter intermittently as the years turn over.

“It’s good. I got this new charger. I thought I lost my charger, but my dad got me this portable one ’cause I’m always losing mine.”

Luddite Nathan: “What? I didn’t know they made portable chargers!”

“You serious?”

“Yeah! After you,” I said at the bus doors during a pause in her talking.

“Oh I’m not getting on, I’m meeting someone.”

“Okay. Hug.” It just felt appropriate. “Stay strong,” I whispered.

“You too.”

They say you need to embrace someone for longer than thirty seconds for the pituitary gland to release oxytocin, the neuropeptide which reduces cortisol levels and promotes feelings of trust and bonding. It’s what’s released right after childbirth and makes mothers forget all the agonizing pain and actually love their child, and is the primary biological basis for positive social connection. I’m not sure the full thirty seconds is always necessary, though. The instant held, a half-second of connected stillness drifting outside of time, as sounds dimmed enough for a whisper to register.

I realized afterwards that was a moment I hope never to forget. But why? I barely know this person. We talked about phone chargers. Why was it so meaningful? I drove up Broadway as oxytocin coursed through my hypothalamus, but that was the how, not the why. Science is great at explaining the former, but not so much the latter (have you ever noticed how kids get bored when we answer scientifically why the sky is blue? It’s because in our answer we’ve only given them the how).

The world is my great love, I realized later. Not her, not particular age or demographic groups, not any one person. I think I just love everybody, the whole collective.*** We all have fervent passions inside of us, and some of us are so good at channeling all that feeling into one person. I marvel and admire that, but I’m wired differently. Only that would for me be missing something huge. To turn away from these strangers whom I adore, in whom I see bits of myself, to be told I couldn’t embrace the masses as I do, that would be akin to… well, cheating on the world! I once watched two men beating each other up in Pioneer Square, and was nearly brought to tears. You guys are my friends, I thought to myself. My human friends. You’re so much better than that.

—

*A friendly face who’s been roaming the streets for only slightly less time than I’ve been driving the bus. You might recall her fromthis writeup on the 70. She’s the girl sitting in the back.

**Naloxone, the opiate antidote.

***One of the reasons I love Terrence Malick’s The Thin Red Line, which unlike most films which are built around protagonists as individuals, considers humanity as a collective.

Nathan Vass is an artist, filmmaker, photographer, and author by day, and a Metro bus driver by night, where his community-building work has been showcased on TED, NPR, The Seattle Times, KING 5 and landed him a spot on Seattle Magazine’s 2018 list of the 35 Most Influential People in Seattle. He has shown in over forty photography shows is also the director of nine films, six of which have shown at festivals, and one of which premiered at Henry Art Gallery. His book, The Lines That Make Us, is a Seattle bestseller and 2019 WA State Book Awards finalist.