Seattle got some bad news from the January 29th One Night Count of the homeless population. The Seattle/King County Coalition on Homelessness reported:

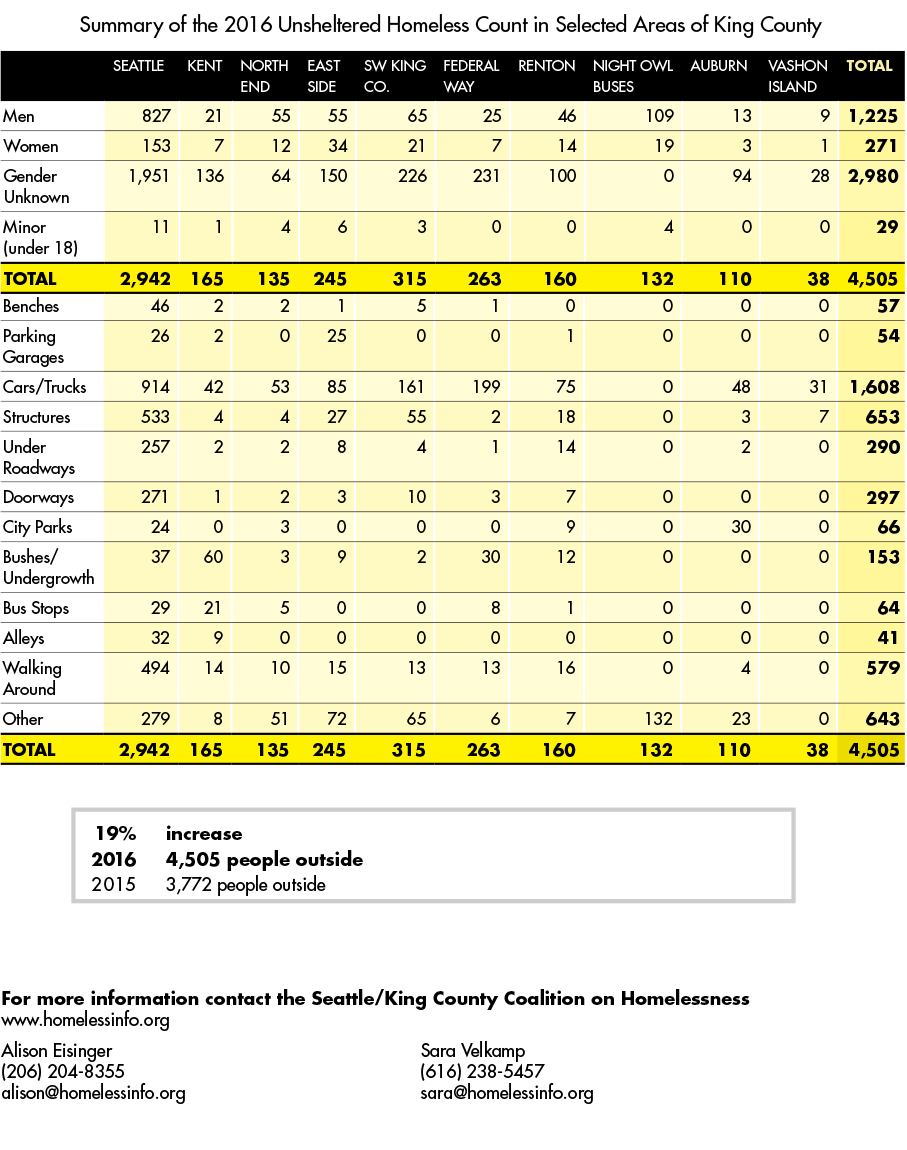

At least 4,505 men, women, and children were without shelter during the three hour street count. This number is an increase of 19% over those found without shelter last year. This number is always assumed to be an undercount, because we do not count everywhere, and because many people take great care not to be visible.

The count was carried out by more than 1,100 volunteers fanning out across King County. Volunteers found the majority of the homeless people without shelter in Seattle with 2,942. The remaining 1,563 were scattered throughout the suburbs, including 315 tallied in Southwest King County, 263 in Federal Way and 245 in the East Side.

Best Laid Plans

Eleven years ago, King County embarked on a 10-year plan to end homelessness by 2015. Obviously that didn’t happen as volunteers counted more homeless people on the streets than ever before. Despite the county’s ambitious goal, the solutions it implemented were woefully inadequate for the multifaceted problem of homelessness.

In a KUOW report, United Way’s Director of Ending Homelessness Vince Matulionis said King County’s 10-year plan didn’t focus enough on root causes, like the lack of affordable housing.

The county was perhaps also caught off guard by how quickly its population grew over the past decade. Many people were drawn to Seattle by the booming economy, but the regional economy’s rising tide hasn’t lifted all boats. Too many people are stuck in dead-end jobs or with no jobs at all. King County has to figure out a way to harness its thriving economy for the good of its poorest residents. Too many people can’t earn enough to afford housing in King County. Unfortunately, the problem now could just be the tip of the iceberg since housing prices are rising much faster than low and middle class wages. Many low-income families are barely making ends meet as is and are one bad break away away from losing their housing.

The Price of Housing

One big facet of the homelessness problem is rapidly rising housing prices. A few months back, the Puget Sound Business Journal reported the Seattle apartment market was “deteriorating” when a few luxury submarkets experienced “price resistance” and saw prices drop slightly — after seeing enormous gains for the better part of decade.

A few national bloggers (Matt Yglesias and Daniel Hertz) used that news to build a case that Seattle had built its way out of its housing crisis. This seemed to be an extremely tenuous and premature conclusion to draw from such limited data. In fact, the report that launched a thousand op-eds actually found a stronger fourth quarter than each of the last four fourth quarters:

Across the two counties, rents increased an average of $9 a month during the fourth quarter. This compares to average monthly rent hikes of $46 during the first three quarters. This, too, would indicate a market slowdown, but [Apartment Insights’ Tom] Cain said that’s not the case because the fourth quarter often is the weakest of the year, with rents actually declining each fourth quarter over the last four years.

The weakness in the market, according to Cain, is at the high end, where 5.4 percent of the units are vacant. Just over 4.5 percent of the mid-range units are not leased, while only about 3.2 percent of the low-end apartments are vacant.

Yglesias and Hertz wouldn’t let a little issue like the strongest fourth quarter in recent history prevent them from declaring “Mission Accomplished.” The One Night Count suggests that slight hiccup in the luxury housing market has yet to trickle down to the low-income housing market. The apparent oversupply of luxury apartments has not led to a decrease in housing pressure on low-income people so far. If housing trickle down works, it does not work very quickly.

Solutions from City Hall

The Grand Bargain on housing crafted in the Housing Affordability and Livability Agenda (HALA) Committee would offer the the City more tools to boost the amount of affordable housing. The City Council still needs to enact many of the committee recommendations this year. And then the HALA programs would need time to work.

In the meantime, we need to boost the amount of shelter beds dramatically and consider adopting a Housing First policy. Utah adopted Housing First and saw a 91% drop in the amount of people who are chronically homeless. Housing First means that being drug and alcohol free is not made a condition for subsidized housing. After a homeless person is housed, the city certainly seeks to address addiction and mental health issues. However, the key is getting people off the streets and into housing. It sounds expensive but consider that the Department Housing and Urban Development estimates letting a person remain chronically homeless costs taxpayers between $30,000 and $50,000 because of services like emergency room visits, psychiatric care, and jail time.

Applying Housing First in King County is going to be more expensive than it was in Utah since our housing is more expensive and our homeless population is larger. However, I think Utah’s success story is too compelling to ignore. We can’t repeat the mistake of the last decade and fail to address the root causes of homelessness. We need a huge influx of affordable housing. We need to try to make our economy work better for the working poor. And we need to stop expecting people to overcome their addiction and mental health issues without a roof over their head.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.