This article originally appeared as a special piece on Strong Towns, which is in the midst of #NoNewRoads week and dedicated Thursday to Washington state coverage.

When state legislators finally passed the Connecting Washington Communities transportation omnibus bill in July, many issued a sigh of relief. With its focus on highway expansion, the bloated $16 billion bill was a toad, but urbanists hoped embracing the toad would turn it into a handsome prince. That metamorphosis would largely take place through the bill’s authorization of the funding authority for Sound Transit 3 (ST3) which will go on the ballot this fall and secure, with the voters’ permission, $15 billion (and perhaps more) in light rail, commuter rail, and bus rapid transit funding in the Seattle metropolitan area.

If ST3 gains voter approval, many people may forgive the excesses of the state transportation bill. And there are certainly excesses. The Urbanist did of a full overview of the bill in July. In short, it contained:

- $9.7 billion that will be spent on local road and state highway projects (megaprojects complete portions of SR-520, the Spokane North-South Freeway, SR-167, and SR-509);

- Another $1.4 billion to be spent on maintenance and repair projects;

- A $1 billion bone thrown to a variety of non-highway projects in the state for pedestrian, bicycle, and transit infrastructure and services (but mostly the latter); and

- Authorization for billions in new local options for Sound Transit, Community Transit, and transportation benefit districts.

The split of $9.7 billion on highway expansion versus just $1.4 billion for maintenance and repair is far from prudent. Transportation is about 10% of Washington state’s budget yet roads are in bad shape. Seattle’s section of I-5 in Seattle is downright dilapidated and sorely overdue for a major overhaul. Emergency repairs happen on an almost monthly basis thanks to 50-year-old expansion joints, bridges, and foundations. Instead of planning for this looming and costly project, the bill uses highway spending to chase economic development in a strategy with little factual basis. Highway-driven economic development is speculative, but maintenance costs of new highways are certainly all too real.

How did they get the money?

Connecting Washington gets most of its $16 billion by raising the state motor vehicle gas tax by 11.9 cents per gallon. Some funding also comes from licensing and registration fees, and vehicle weight fees for passenger vehicles and haulers. Sound Transit 3, on the other hand, would get its funding through raising property taxes and a mix of other sources within the Sound Transit taxing district covering portions of King County, Pierce County, and Snohomish County.

What do cars and trucks get?

Here’s how the legislature divided some of the highway spoils:

- $1.9 billion: SR-167/SR-509 Gateway project

- $1.6 billion: SR-520 “Rest of the West”

- $1.3 billion: I-405 Lynnwood to Tukwila Corridor Improvements

- $879 million: US-395 North Spokane Corridor

- $494 million: JBLM Congestion Relief Project

- $426 million: I-90 Snoqualmie Pass

- $335 million: safety projects, including I-90/SR-18 interchange, US-2, SR-20, and others

The biggest megaproject on that list, the I-5 and SR-167 interchange, expects to improve mobility near the Port of Tacoma by beefing up freeway interchanges in Fife. At the very least, motorists will be able to sit in swanky flyover ramps during traffic jams.

The Washington Department of Transportation (WSDOT) studied implementing SR-167 tolls and suggested the highway network would actually operate better with full tolling in place. Tolling would cover the maintenance and operating costs and also supplement capital costs to a small degree (the study predicted $65 million). Tolling is a great way get a dedicated maintenance funding stream for highways and avoid the colossal maintenance backlogs we find ourselves confronting. That said, tolling on the highway is far from certain given the noisy backlash to the proposal to toll I-90 and to the recent addition of tolls on I-405. The decision isn’t expected until a few years down the road.

What do fish get?

- $300 million: fish barrier removal

What do lenders get?

- $2.75 billion for debt service, highlighting how significantly WSDOT has relied on credit to build out the highway network.

What do people get?

The bill slots $1 billion for multimodal improvements. That’s serious money, even if its dwarfed tenfold by highway spending. The multimodal money is doled out as follows:

- $200 million for the Regional Mobility Grant Program

- $200 million for special-needs transit grants

- $111 million for transit-related project grants

- $110 million for the Rural Mobility Grant Program

- $75 million for pedestrian and bicycle safety grants

- $56 million for Safe Routes to School grants

- $41 million for the Commute Trip Reduction Program

- $31 million for the Vanpool Investment Program

- $89 million for the Legislative Evaluation and Accountability Program Committee pre-identified, tiered pedestrian and bicycle project list.

As you can see most non-highway spending goes to transit, while $131 million goes to bicycle and pedestrian upgrades. Another sign of WSDOT’s limited commitment to pedestrians is that among their thousands of employees, just one is tasked with Safe Routes to School. Similarly, one employee handles the entire active transportation portfolio. No wonder pedestrian facilities are so often overlooked. The multimodal investments are some of the soundest ones Connecting Washington makes. Does a fractional amount of multimodal investments and the promise of ST3 mean the whole bill is a net positive? That’s a tougher question to answer.

My educated guess is that these new highways will be a waste of money. WSDOT promises reduced congestion, but highways induce demand so the new highways could become just as clogged as the old highways. Tolling would help counter induced demand, but the bill didn’t address tolling so it might not happen.

Boosters cite the importance of good freight connections to the Ports of Tacoma and Seattle to further economic development. Note, I-5 already offers freight connections from the ports, albeit in lanes that are often heavily congested. The problem is too many people drive and at the same times of day. Adding highways to the overall transportation system does not discourage people from driving. It encourages it. That’s why WDSOT quest for highway expansion is a never-ending one if solving congestion drives the decisions rather than human mobility.

The City Versus The Hinterlands

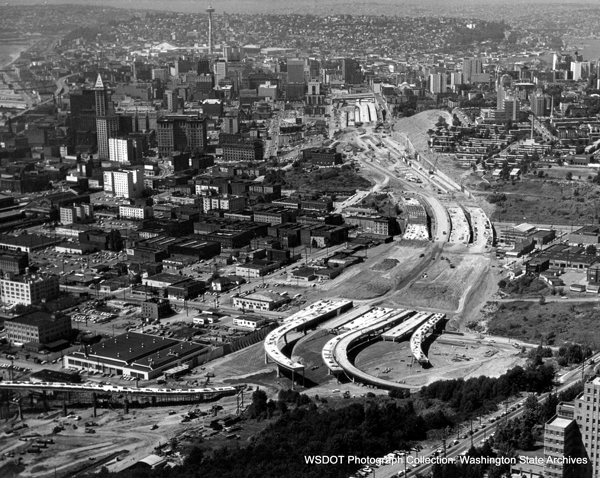

WSDOT and Seattle don’t often see eye to eye. Often suburb-city and rural-city tensions play out in transportation politics. Seattle, with a population of about 675,000 in a state of more than 7 million, often loses out in its priorities. In the 1960s when WSDOT dug the I-5 trench through dense Seattle neighborhoods, such as First Hill and Eastlake, it did so over the protests of local residents. Tens of thousands were displaced in the name of highway speed.

Since then, WSDOT hasn’t done anything that blatantly violent to Seattle’s urban fabric and its people. But that is still WSDOT’s attitude, and the violence of that original sin still damages Seattle on a daily basis. Motorists exiting and entering freeway ramps run over pedestrians trying to cross the I-5 chasm. Pollution from a quarter million cars and trucks belches up from the pit and into human lungs.

Seattleites obviously extract some utility from I-5—when it isn’t gridlocked clear to Tacoma. But, as quickly as WSDOT conjures $4 billion to replace the SR-520 bridge to Bellevue, it struggles to keep up on routine I-5 maintenance (rather than emergency maintenance) in Seattle and ignores pleas for freeways lids to stitch Seattle’s east side neighborhoods back together with downtown and South Lake Union. Perhaps I-5’s pending but long delayed overhaul in Seattle could be paired with freeway lid construction to minimize the disruption to operations. We don’t hear about that from WSDOT, though.

Bertha and the Giant Sinkhole

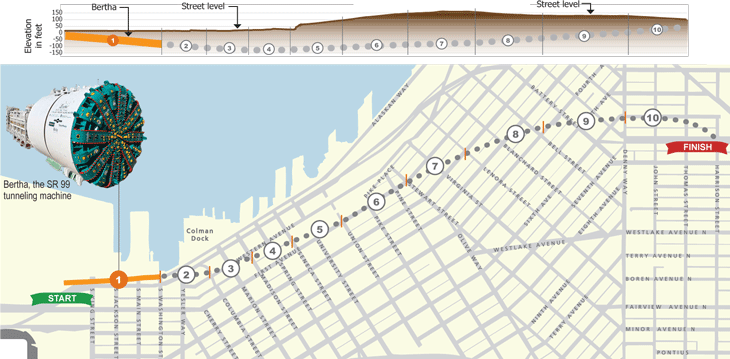

The recent symbol of WSDOT’s ineptitude is the Bertha tunnel. Seattle wanted to replace the structurally unsound Alaska Way Viaduct with a simple street-level boulevard, but, bowing to pressure from suburban commuters, WSDOT went with a deus ex machina option of buying the world’s largest tunnel-boring machine (TBM) to dig a $4 billion tunnel to bypass downtown. WSDOT christened the TBM “Bertha” in honor of Seattle’s first female mayor Bertha Knight Landes.

I’m not sure Ms. Landes would have been honored because, if you haven’t heard, the project isn’t going so well. Last month, Bertha finally started digging again following a two-year hiatus caused by a breakdown. Unfortunately, a sinkhole appeared shortly thereafter and drilling was suspended again. The tunneling was only supposed to take 14 months, but we are already on our third year and the tunneling is about 10 percent done. Cost overruns are expected. All this for a tunnel Seattle didn’t really want and which won’t serve transit since its bypasses downtown.

WSDOT’s history of justifying highway megaprojects by any means necessary while pedestrians, bicyclists, and transit get shortchanged is why many Seattleites don’t trust their promises. The latest transportation bill wasn’t the one to fund Bertha, but the state’s willingness to bury $4 billion in a Bertha sinkhole shows exactly where its loyalties lie.

The legislature didn’t have to give us a bloated toad. A wiser policymaking body would have given us the prince straight away. Instead, we are left trying to learn the art of transfiguration and pull transit out of a highway sprawl bill. And we just might do it if we pass ST3 this November.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.