As a practicing professional and writer I’m frequently asked to represent the “urbanist” perspective on particular issues. This has gotten me thinking about what it means to be an urbanist, how urbanism is defined, and if I actually fit the description. In this post, I will explore these questions and confirm that there are specific aspects of urban living and public policy that I believe in and will continue to advocate for

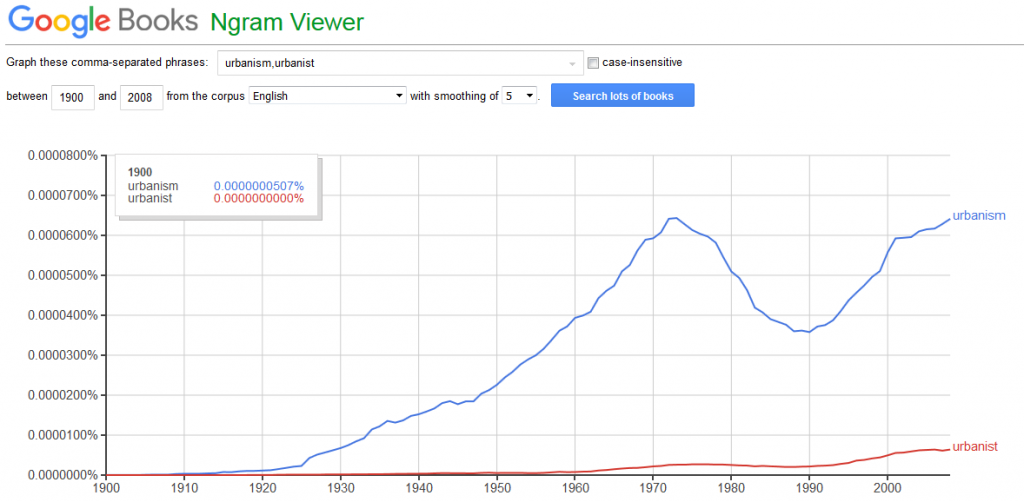

The term “urbanism”, and the subsequent followers deemed “urbanists”, dates back quite some time but has recently seen an increase in use. Google’s experimental Ngram Viewer, drawing from millions of books, produced this chart of the term’s usage over the past century. Urbanism has apparently been referred to in the literature as soon as city planning became its own profession in the 1920s.

A comparison of the use of “urbanism” and “urbanist” over the past 100 years. (Google Ngram Viewer)

Perhaps what is most publicly associated with these terms (and responsible for those upward bumps in the 1990s) is the New Urbanism movement. Reacting to decades of sprawl and its negative consequences, New Urbanism seeks to return American neighborhoods to the human-scale and mixed-use style of pre-1950s land use patterns. However, many of the actual developments that have flown the New Urbanism banner have been criticized for only using architecture as a literal facade for auto-centric planning.

Former Seattle mayor Michael McGinn recently penned an opinion piece for Crosscut arguing that the new City Council hasn’t quite reached the urbanist status that many local advocates have hoped for. In doing so, he offers a definition of what it means to be an urbanist:

At the core, urbanists want more people living in cities, so they support more urban housing of all types. They prioritize walking, biking and transit, and support a high quality shared public realm. Parks, nightlife, theaters, transit and taxis can replace backyards, TV rooms and private cars. That way we can live well with less stuff, sprawl and pollution.

I’ll go a little further, and say urbanists prefer bottom up, granular, and seemingly chaotic innovation to top-down planning and mega-projects. Think the “Main Street” of neighborhoods with food trucks and lots of little stores, as opposed to tax-subsidized big box stores with legally required massive parking lots. Bike lanes, crosswalks and plazas instead of public garages and new highways.

Urbanists believe that mixing people and ideas creates wealth in a city. Why else would people choose to live so close to each other? Cities, therefore, should be open to people of every background, ethnicity, race and class to maximize the potential from our human capital.

To summarize, urbanists want more people (of all types) to have equal access to housing variety (apartments, townhomes, backyard cottages, houses, duplexes, etc.), more ways to get around (transit, walking, bicycling, ride-share, vanpool, etc.), more to see and do (parks, cafes, bars, museums, shops, etc.), and to have more grassroots influence on city government.

Because a picture is a worth a thousand words, to illustrate, urbanists want less of this:

And more of this:

One thing I’d add is that most urbanists are also environmentalists at two scales. At the smaller scale, urbanists are interested in public infrastructure that uses water, energy, and building materials efficiently. They also promote natural methods for cleaning stormwater, disposing of solid waste, and providing recreation space. At the larger scale, urbanists know that urban living is a net positive for the environment because it reduces society’s impact on natural landscapes and ecosystems. Every apartment a city builds is one less single-family home that knocks down trees, destroys wildlife habitat, and puts another carbon-emitting car on the highway.

McGinn’s definition of urbanism seems to be a recent evolution in the academic and public discourse. Urbanism has established itself as an independent ideology of planners, architects, social justice organizations, transit advocates, and others who cherish the benefits of urban living. It has become the anti-thesis to suburbanism, an undeniably powerful current running through American society. The need for such bottom-up efforts reflects the fact that suburban thinking is the status quo even in large cities.

Despite this, I’ve never met anyone who calls themselves a suburbanist or even a ruralist. There are few, if any, organizations dedicated to suburban ideals like free street parking and minimum lot sizes, at least in Seattle. Instead, there are an abundance of groups that fight for traffic safety, police reform, affordable housing, and other urbanist principles.

Since enrolling in architecture school, and more so after moving to Seattle and studying urban planning, I have slowly realized that I do care about everything that McGinn describes. But I wasn’t thinking directly about that when I came up with the name, The Northwest Urbanist. I wanted to reflect the geographical area I write about, yes, but I found the term “urbanist” simply to be the most straightforward way to announce that this website is generally focused on cities. Back in 2013 “urbanist” didn’t seem to be in common usage, but today it’s applied as a label with as little discretion as the terms “affordable” and “sustainable”. Perhaps I’m a hipster urbanist.

A 2010 opinion letter in The Washington Post offers an explanation for why urbanism has caught on so suddenly: the decline of urban populations is reversing and more people are moving back into center cities, especially younger people who are just beginning their careers and families. Young people have always preferred the hustle and bustle of the cities. But today they are driving less than ever (and getting their drivers licenses later), they allegedly prefer the urban amenities that compact development has to offer, and they are often burdened with student debt and limited job prospects.

To expand on that last point, it’s clear that people have economic motivations for moving to cities. Just as it has been for millennia past, today cities simply have a much higher concentration of jobs and networking opportunities than outlying areas. And if you ditch your car (or never had one in the first place like me), living in the city may be cheaper than the alternatives even if urban apartment rents are higher than in the suburbs. That’s because commuting by car is a huge expense if you’re living on a limited income; Consumer Reports found that owning typical cars cost in the range of $5,000 to $9,000 per year, accounting for fuel, fees, maintenance, insurance, and parking.

Further, the preference for (or necessity of) job-hopping in today’s economy is tied to the flexibility of renting rather than owning. Even if younger people do want to own a home, debt and the lack of affordable options in urban centers make saving up for a down payment difficult, if not impossible, before they are much farther into their career than previous generations of homeowners were. For cash-strapped young Americans, urban apartment living simply makes financial sense.

To be sure, other demographic groups have reasons for preferring cities. Older populations, especially the retiring Boomers, may find that aging-in-place in cities and walkable suburbs is a necessity when they are less able to drive and need quick access to healthcare facilities. Immigrants have traditionally settled into urban enclaves for the proximity to familiar people, food, and customs. People identifying as LGBT prefer cities because they have a better chance of finding social acceptance. You get the idea.

But when people started returning to the cities in the 1990s and 2000s, they often found a disconnect between emerging modern lifestyles and the state of infrastructure and neighborhoods. Urban freeways, dilapidated buildings, lackluster transit service, and awful streets for walking and bicycling don’t mesh well with emerging lifestyles that increasingly value mobility, socializing, and a variety of cultural experiences. If they’re going to give up or forgo big houses and cars, the newcomers decided they ought to have access to high-quality public spaces and infrastructure.

This collective of market demands helped bring about the urban renaissance that many American cities are experiencing today. This is happening in the form of big trends like apartment construction booms and the relocation of corporate headquarters from suburban office parks, along with smaller changes like the emergence food trucks, the revival of streetcars, better parks and public spaces, and beautiful civic buildings.

This big urban shakeup clashes with the values of preservationists and single-family homeowners. New residential development devalues the investment of homeownership and threatens to alter the physical appearance of neighborhoods. In this context, it’s only natural that NIMBYs and urbanists may not share the same values. Urbanists tend to care more about the neighborhood’s characters than architectural “character”. The manifestation of urbanists’ values results in changes to the built environment, which for the past 70 years has been typified by a rigid monotony of living in large houses, traveling in cars and on highways, and shopping at big box stores.

That old way of building is boring. There is nothing less exciting to me than a land-scraping strip mall surrounded by a pad of asphalt and cookie-cutter boxes called “starter homes” and “garden apartments”. Life in that environment is guided by a monotonous process: drive to work, drive to the store, drive to school, drive back home. Because everyone else drives and the distances are so vast, it takes forever to get anywhere and there’s little chance for spontaneity and diversity in daily routines. When people spend all of that time driving, they also can’t safely connect with friends on their phones, a valued possession in the era of digital socializing. Poor and carless people in that environment have to rely on unsafe, inconvenient, or even non-existent walking paths and little or no transit service.

Maybe it’s because I’m young and energetic, and maybe my preferences will change with age, but right now, I crave more excitement than what the vast majority of America has to offer. I want to be exposed to experiences, ideas, and people that challenge my world view and which might make me uncomfortable, but which ultimately I can enjoy for their contribution to my life and my development as a human being. This level of exposure requires access to a lot people who live and work in a relatively small space.

Only cities have that critical mass which allows interesting random stuff to happen. Whether it’s passing by a gaggle of Santas or a bucket drummer on the streets, running into a friend in the smallest random coffee shop, discovering niche groups with mutual interests and hobbies, or experiencing exciting art and concerts, cities have what it takes to keep life interesting. I want to ensure that places like Seattle retain and grow the mix of characters and culture that makes cities exciting. That’s why I call myself an urbanist.

This article is a cross-post from The Northwest Urbanist.

Scott Bonjukian has degrees in architecture and planning, and his many interests include neighborhood design, public space and streets, transit systems, pedestrian and bicycle planning, local politics, and natural resource protection. He cross-posts from The Northwest Urbanist and leads the Seattle Lid I-5 effort. He served on The Urbanist board from 2015 to 2018.