The University of Washington (UW) is one of Downtown Seattle’s largest landowners, but you wouldn’t know it just by being there. The university controls about eleven acres of prime real estate where the original campus was founded in 1861, known as the Metropolitan Tract, and owns over 1.5 million square feet of office space there. The portfolio includes icons like the modernist Rainier Tower and historic landmarks such as the Fairmont Olympic, the city’s only 5-star hotel. The recent expiration of a ground lease is prompting plans to redevelop the Rainier Square shopping center (pictured above), but the concept is little more than just another office tower with pricey condominiums. The Tract’s lack of contribution to Downtown life prompted a group of graduate students to propose better alternatives.

Myself and eight other students were part of the annual urban design studio at the university’s Department of Urban Design and Planning. Under the direction of Professor Ron Kasprisin, we began in Spring 2014 by collecting basic information about the site and building a large context model (pictured below). When asked for drawings, data, and their guidance, the UW Real Estate Office actually told us to stop and find another project. We pressed on anyway.

In the fall, we reconvened to do additional site analysis as a group and share comparable case studies. I found the CityCenterDC project to be an applicable example of downtown redevelopment. There, about ten acres of an old convention center site are being built up with mixed-use blocks within reconnected streets, pedestrian alleyways, and new open spaces. I also looked at the pedestrianization of Times Square. I took these ideas to my own full site redesign, presented below. But first, a little history.

The university decided to relocate in 1895 after a special legislative committee found that “The grounds of the university are…neglected and forlorn, and have been for years. An old ramshackle fence surrounds them, and often in places…cows invade and trespass.” It was determined that more ample grounds far from the growing city were needed, and that the campus is “…best removed from the excitements and temptations…” of city life. Of course today, the 600-acre UW campus is surrounded by one of the city’s densest neighborhoods. The state legislature allowed the university to retain rights to its original campus, which was a financially sound decision. Today, the UW earns $8 million per year from the Tract, bolstering the university’s capital projects and building fund.

Intriguingly, we learned that the UW actually owns the land beneath some Downtown streets, an unusual arrangement in any city. Included are parts of University Street, Fifth Avenue, and the alleys behind the Skinner Building and Financial Center. The UW simply permits the City of Seattle to maintain these corridors as public right-of-way, and can revoke the permit at any time. The City’s only attempt to resolve this was over 100 years ago when they managed to obtain an easement over Fourth Avenue; in 1987, the City successfully sued to assert its air rights and force the UW to tear down a skybridge over that street. However, the portions of the Tract north and south of Fourth Avenue are considered to be large contiguous parcels, and so the rest of the streets count towards floor-area-ratio (FAR) limits. The tract is zoned Downtown Office Core 1, which allows unlimited heights but restricts building floor area to 20 times the site’s size.

My colleagues have a mixture of backgrounds, some having little or no design experience at all before the studio. But each proposal was impressive in its own right. Several looked at the role of topography in the urban landscape, with one proposal to form new buildings through historic contours and another to establish an engineered ground plane ten stories above the street level. Others looked at maximizing leasable square footage by sinking development underground or going tall within the existing urban fabric.

I was following the ongoing saga to establish a Downtown elementary school, which is currently on hold, and realized that this site is an opportunity to vastly increase residential capacity and make Downtown a 24-hour family-friendly neighborhood. This would require residential towers to replace existing buildings, so my first step was to look at which structures were worth preserving and which could go. Simplistic criteria based on architectural significance, economic productivity, and social contribution found that much of the site could be wiped clean. The Olympic Hotel, Rainier Tower, Skinner Building, Cobb Building, and Financial Center would stay. I assumed the federal post office and a private parking garage along Third Avenue would be acquired.

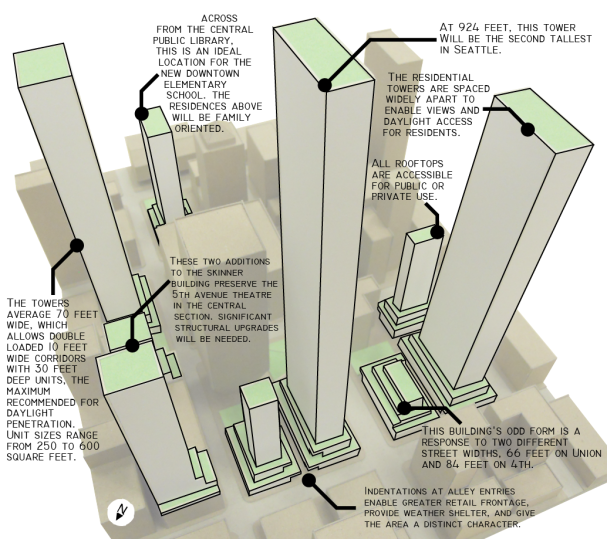

Working within these constraints, I began focusing on the human scale. On the two largest blocks, I envisioned restored 20-feet alleyways to connect the site and to create mid-block pass-throughs for pedestrians. The ground floors of almost every new building will be required to be lined with retail (a total of 136,000 square feet), ensuring the alleyways will be active and vibrant places. The ground floors are also indented to create triple-width alley entries, giving passerby more time to consider entering (12 seconds versus 4 at walking pace) while providing small gathering spaces and weather shelters. With the Tract currently lacking adequate public space, I also designated five sites for larger plazas and parks throughout the site. Their widths will be 75 feet, about the maximum distance that humans can recognize facial features.

From there, a recent trip to Vancouver spurred an interest in the “podium” style of skyscraper, in which a tower is placed upon a wider, shorter base that is more relatable to people at the street level. I developed a form-based code that dictates the dimensions of the skyscrapers: two podiums are required, with their height being half the fronting street width and the setback being a quarter of the width. This results in the street wall being three to five stories tall, which forms a comfortable pedestrian realm. The tower heights are limited to one (low-rise), five (mid-rise) and ten (high-rise) times the street width, which varies between 66 and 96 feet. Study models showed the issues with putting towers too close together, so the various tower heights are distributed throughout the site. But all of the rooftops and podiums are accessible for any number of uses, such as outdoor dining or private play space for residents. And other than the ground level, all of the podiums’ floors are designated as “flex space” and open to any use permitted in Downtown. There is some 590,000 square feet of flex space, a net gain for possible office space after Puget Sound Plaza and the IBM Building are demolished.

The setbacks result in towers that are between 35 and 90 feet wide, which is ideal for a mixture of residential unit sizes. The narrower and shorter towers could contain microhousing or lodging, while the larger units will be big enough for three- or four-bedroom family apartments and condominiums. After considering varying unit sizes, mechanical floors, and hallway space, I calculated that the overall design can support 4,700 new units. With Downtown averaging 1.37 people per household and having a 3.8 percent vacancy rate, this new “Metro Neighborhood” could be home to over 6,000 new residents. This will support the included retail and further solidify the downtown as Puget Sound’s center. It will also exploit existing infrastructure; the Downtown transit tunnel has an entry on the site at Third and University that will provide connections to the UW campus, the airport, Bellevue, and beyond.

There are a number of other interventions in the plan. Across from the Central Public Library, an eight-story parking garage is demolished to make way for a 100,000 square foot elementary school in the podium of a residential tower. The Rainier Tower’s curved concrete base is enclosed with glass walls to create an indoor plaza or an architectural museum. Next to this is a low-rise retail building with a sloped roof-park that will provide impressive views of surrounding streets. Diagonal from that is also a terraced low-rise in front of the Financial Center that will have extensive outdoor space for shoppers. The Skinner Building’s two wings are modified with residential towers, while its central 5th Avenue Theater is untouched. The site plan also shows complete street layouts with parking, crosswalks, street trees, and all of the protected bike lanes that are designated in the Seattle Bicycle Master Plan.

The studio was a worthwhile exercise in exploring how a major Downtown site could be transformed to better serve people, the city, and the region as a whole. Though the UW’s management of the Tract is conservative and risk-averse, I’d argue that the Metro Neighborhood proposal is among the more feasible options and would certainly generate more revenue than the current portfolio.

This article is a cross-post from The Northwest Urbanist.

Scott Bonjukian has degrees in architecture and planning, and his many interests include neighborhood design, public space and streets, transit systems, pedestrian and bicycle planning, local politics, and natural resource protection. He cross-posts from The Northwest Urbanist and leads the Seattle Lid I-5 effort. He served on The Urbanist board from 2015 to 2018.