Uber is launching a brand new ridesharing service in Seattle today. uberHOP, as it is known, is a first-of-its-kind pilot for the company globally, and joins the company’s growing suite of innovative offerings, including uberPEDAL, uberPOOL, and uberCOMMUTE. The service is built around the concept of connecting riders with Uber drivers on some of the city’s most popular routes. Essentially, Uber drivers will operate a fixed route service much like scheduled transit does.

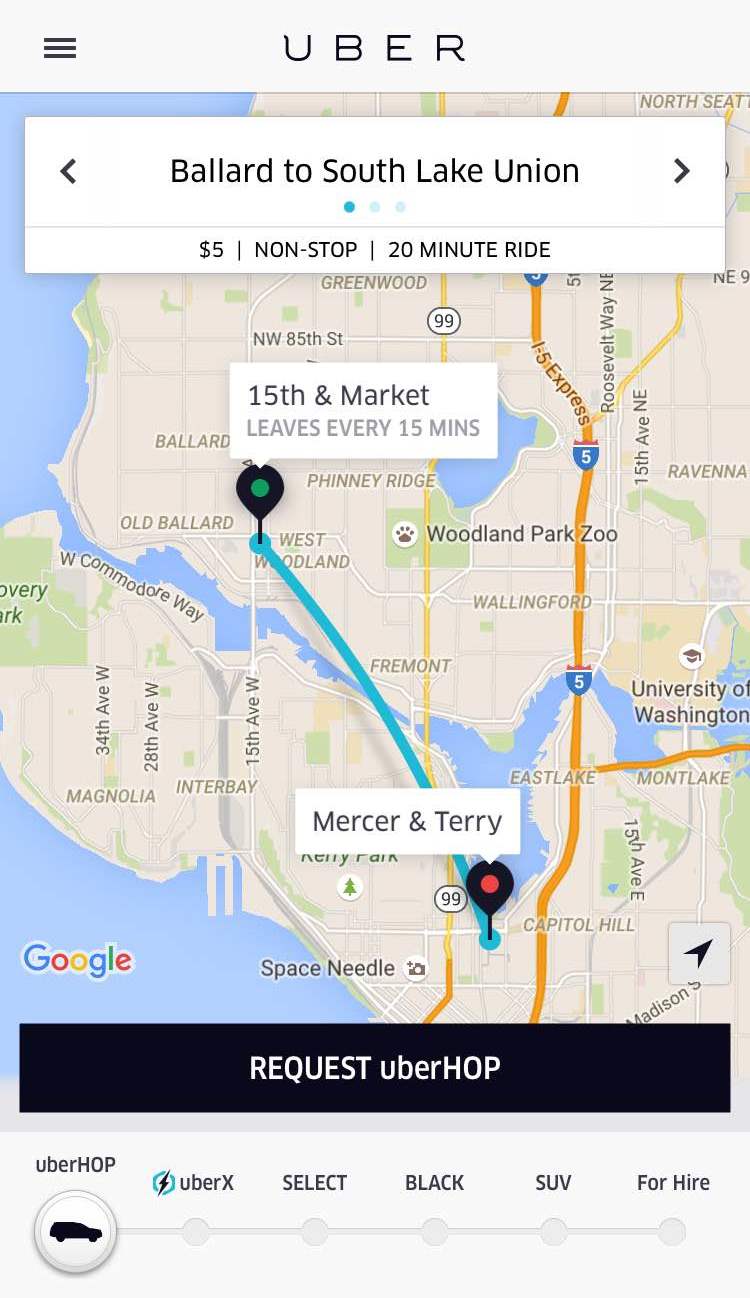

The model itself is pretty straightforward. Pickup and dropoff locations will be designated, meaning that riders can’t just hail a pickup or dropoff at a whim midway along the routes. Instead, riders have to book their trip ahead of time and share the ride with others. Typically, five or six riders will be matched with an uberHOP departing at a common time and location. Perhaps most importantly, riders have to arrive to the pickup point prior to the departure time, or face a fare charged to their account and forego the ride.

Payment is no different than any other Uber service. Riders pay through the app upon booking their trip. Flat rate fares are set at $5 per trip, meaning that rides will be incredibly competitive with other options.

Uber is banking the success of this new service on commuters. The company plans to run the services on weekdays only during the morning and evening rush.

Three initial corridors have been chosen for the uberHOP service:

- Ballard (15th & Market)– South Lake Union (Mercer & Terry)

- Fremont/Wallingford (Bridge Way & Stone Way) – Downtown (1st & Seneca)

- Capitol Hill (14th & Pike) – Downtown (1st & Seneca)

Supporters of transit might wonder what all of this means. Indeed, the planned corridors of uberHOP are in direct competition with existing service from public transit and private transit operators. There’s little doubt that Uber hopes to poach some of these riders with comfy, guaranteed seats. Yet, other ridesharing companies like Lyft are actively marketing their service in major cities across the country as complimentary to transit. It’s too early to tell how much, if any Uber will actually impact transit ridership, or if any beneficial relationship will bear out from a service like this. Uber, of course, hopes to have this service scale and take it elsewhere.

But this peak-oriented service means that Uber will be moving riders through major chokepoints at some of the most trafficked hours of the day, calling into question how competitive it will really be over the status quo. On top of that, riders are forced to start and end their trips at two points, meaning that the overall utility of the service is greatly reduced by few destinations and walksheds.

Similar private fixed route services like uberHOP have been met with mixed success in urban metros across the United States.

Leap Transit, a private bus outfit from San Francisco, provides a cautionary tale where going the route of fixed transit service doesn’t necessarily pan out. The company was built upon the foundations of the Bay Area tech culture as a disrupter of the status quo and an innovator with a lavish du jour. Farhad Manjoo of The New York Times explains:

Leap, which raised $2.5 million from some of the industry’s best-known investors, charged riders $6 to get across San Francisco, nearly three times the cost of riding a city bus. Its primary draw was luxury. Each bus had a wood-trimmed interior outfitted with black leather seats, individual USB ports and Wi-Fi. The buses also offered a steady stream of high-end snacks, sold via app.

Leap struggled though, in part because of its antagonism toward the people it set out to serve:

Leap’s troubles started early. It began a private bus service in San Francisco in 2013. Even though it had no valid city or state license, the company decided to use city bus stops to pick up and drop off passengers — a practice that earned it immediate scorn from city officials and cast the service as part of the tech-versus-everyone-else narrative of gentrification in San Francisco. The company went on hiatus in 2014 while its founders worked with state and city officials to win a preliminary certificate to operate.

When Leap began operating again in March, the company struck a sour note with the news media, embracing so many techie stereotypes you could be forgiven for thinking it was cooked up by the writers of HBO’s “Silicon Valley.”

Eventually, state regulators sent a cease-and-desist letter to the company causing the operator to curtail service, and ultimately never starting back up again.

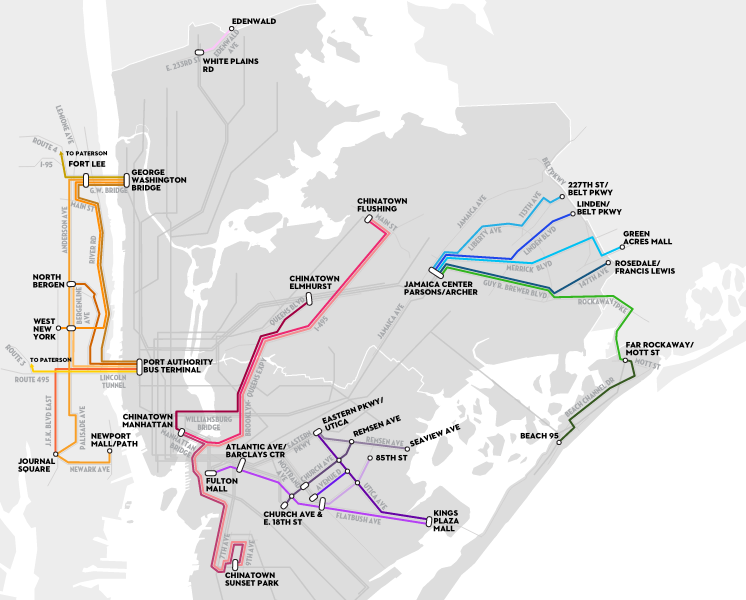

Yet in New York City, “dollar vans” have become increasingly popular ridesharing services. They’re a refreshingly informal, low-tech, no-frills solution to the transportation needs of many New Yorkers. For only a few bucks, riders can get to the far away fringes and hard-to-reach areas of the outer boroughs from key transportation hubs of the New York Subway. Most of the routes don’t directly compete with frequent, high capacity transit offerings, and schedules are fixed with no way to use apps to hail a pickup. Aaron Reiss of The New Yorker documented the origins and success of this phenomenon:

In 1980, when a transit strike halted buses and subway trains throughout New York’s five boroughs, residents in some of the most marooned parts of the city started using their own cars and vans to pick people up, charging a dollar to shuttle them to their destinations. Eleven days later, the strike ended, but the cars and vans drove on, finding huge demand in neighborhoods that weren’t well served by public transit even when buses and trains were running. The drivers eventually expanded their businesses, using thirteen-seat vans to create routes in places like Flatbush, Jamaica, Far Rockaway, and downtown Brooklyn.

Today, dollar vans and other unofficial shuttles make up a thriving shadow transportation system that operates where subways and buses don’t—mostly in peripheral, low-income neighborhoods that contain large immigrant communities and lack robust public transit. The informal transportation networks fill that void with frequent departures and dependable schedules, but they lack service maps, posted timetables, and official stations or stops. There is no Web site or kiosk to help you navigate them. Instead, riders come to know these networks through conversations with friends and neighbors, or from happening upon the vans in the street.

uberHOP is neither of these, of course; it’s an all tech, low-frills, and honest-to-goodness approach to moving small groups of people to common locations. But will it be successful? And how, if any, will it change the way that the masses get around Seattle?

Stephen is a professional urban planner in Puget Sound with a passion for sustainable, livable, and diverse cities. He is especially interested in how policies, regulations, and programs can promote positive outcomes for communities. With stints in great cities like Bellingham and Cork, Stephen currently lives in Seattle. He primarily covers land use and transportation issues and has been with The Urbanist since 2014.