Yesterday, I covered the need for lid parks in Downtown Seattle and what they should be used for. In this article, I look at (very rough) cost estimates for lids based on existing and proposed projects across the United States. From those projects, I select handful to study in-depth and make recommendations on design and operations of future lid parks.

Lid Inventory and Cost Estimating

In analyzing a lidding of I-5, my next step was to build a list of completed and proposed lid projects in the United States. To my knowledge, I am the only researcher to have done this and this is the first publicly available database. I sought data on completion year (to adjust costs for inflation), original costs, and size. Most of the data was acquired through online sources or by contacting local and state officials. Significant gaps remain where, for various reasons, these officials did not have the information.

The map below identifies completed lid projects in red and proposed in green. (Please contact me if you have suggested additions or corrections.)

The average cost of completed lid parks comes in at $13.2 million per acre. Proposed lid parks have a higher average cost estimate of $25.1 million per acre, a number skewed upward by large, unofficial proposals in Austin, Los Angeles, and Chicago. The average cost between completed and proposed projects is a modest $19 million per acre, a number comparable to the latest project in Dallas which came in at $21.5 million per acre. Locally, Seattle’s Freeway Park and the Aubrey Davis Lid on Mercer Island both cost about $18 million per acre.

Contrast these numbers with the exorbitant estimates of two related studies. In a 2009 report (15 MB PDF) for the City of Seattle, engineering firm CH2MHill estimated that lidding I-5 just between Spring Street and Madison Street (1.5 acres) would cost at least $70 million per acre. In a 2013 study (47 MB PDF) of the Convention Center expansion, design firm LMN Architects estimated a 1.1-acre lid between Pike Street and Pine Street would cost $52 million per acre, and a 2.3-acre lid would cost $102 million per acre. These numbers are three to five times greater than real world examples. While Seattle certainly has unique challenges that may increase costs, these estimates are far removed from the reality of actual lid projects and should not be used moving forward.

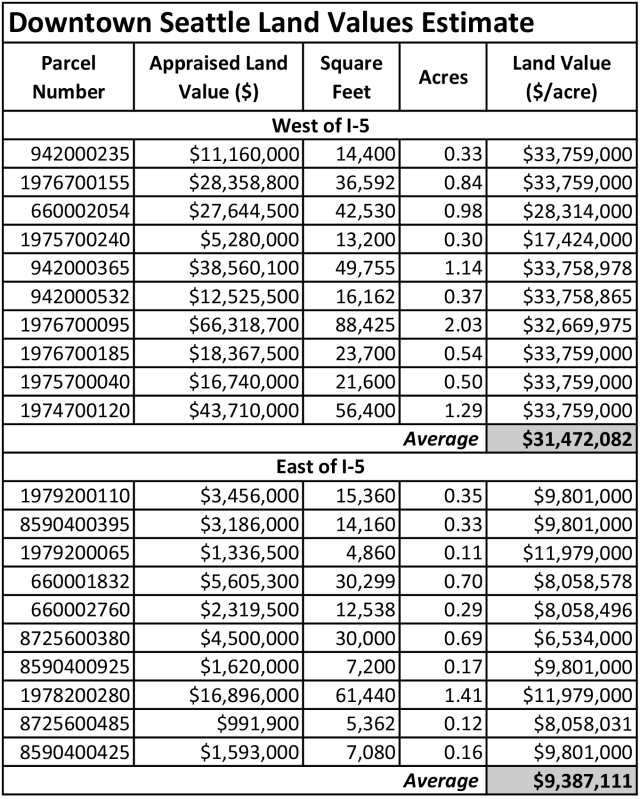

A conservative estimate, then, is that new lids in Downtown Seattle can be expected to cost $20 million and $25 million per acre. This can be compared to appraised land values to illustrate the minimum cost of an alternative method for creating any new Downtown park: buying private land. I did a random, unscientific sampling of private properties near the study area. West of I-5, which is mostly zoned for skyscrapers, the average appraised value is $31 million per acre. Recent sales show that market values are even higher: the 4-acre Convention Place bus station sold for $147 million, or about $37 million per acre. In the east, zoned for mid-rise buildings, the average appraised value is $9 million per acre.

The cost of lids would be much less than acquiring private property in the core of Downtown. And unlike traditional parks, lids would not remove any land from the local tax base, avoiding a drain on revenue for municipal services and infrastructure. This is especially important considering the high value of land in Downtown. Using lids to create large central park also avoids the dramatic and costly process of eminent domain.

As discussed later on, I recommend lidding approximately 8.4 acres, resulting in a rough cost estimate of $168 to $210 million. That can be rounded up to $250 million to account for rebuilding retaining walls and overpasses, traffic system modifications, and improvements to Freeway Park.

Paired with the massive benefits of freeway lids, and relative to the enormous megaprojects going on Seattle right now, a price tag of $250 million is an incredible bargain. Compare this cost to a series of local mega projects:

- $4.6 billion for the SR-520 rebuild;

- $3.1 billion (and counting) for the Alaskan Way Viaduct replacement project;

- $1.9 billion for the University Link light rail extension;

- $1.1 billion for the Waterfront Seattle program;

- $930 million for Seattle’s renewed transportation levy ($930 million); and

- $200 million for the City’s anticipated contribution to a proposed SoDo sports arena.

Lids in Downtown can easily be broken into phases; I’ve proposed building one section at a time between various street overpasses, starting with the smaller sections. Additionally, the funding options are many. Bonds, levies, and local improvement districts are local sources that have a history of voter support (e.g., the Seattle Park District, the $290 million waterfront seawall bond, and the $73 million Pike Place Market renovations levy).

Federal transportation grants are a competitive but likely source for a project of this scale and impact. WSDOT and the Washington State Legislature will also be interested because state right-of-way is involved, and at the very least the City of Seattle could be deeded the air rights at no cost. Seattle’s many corporate headquarters and wealthy residents also make philanthropy particularly promising; private donations funded 48% of Dallas’ new freeway lid.

In short, funding a public project this moderate in scale for a city the size of Seattle is not an issue. The larger concern is how lids should be designed to best benefit the many needs of the public and fit into the built environment of Downtown. For that, I dove into the details of several other lid projects.

Case Study: Klyde Warren Park

Klyde Warren Park is a 5.2-acre lid in downtown Dallas, Texas that opened in 2012 at a cost of $110 million. It spans over eight lanes of TX-366 for three city blocks. It was designed by landscape architecture firm OJB. Since opening, the park has seen over one million visitors per year, the surrounding blocks have experienced significant real estate investment, and in 2014 it won the Urban Land Institute’s award for urban open space.

The park’s design and operations offers many lessons for future lid parks in Seattle. So last spring, I visited Dallas to see its success firsthand. I talked with Michael Gaffney, vice president of operations at the nonprofit Woodall Rodgers Park Foundation (the park is owned by the City of Dallas but managed by the Foundation), to get some local insight and observe the space. From that meeting, I came away with a number of observations and important details from Gaffney.

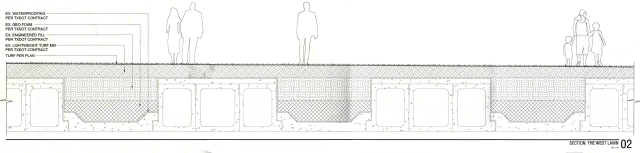

Firstly, the park is flat and open and visitors can enter it from almost any point along its perimeter. These characteristics play a huge role in the park’s success by encouraging casual use at all times of day. Open sight lines, widely spaced trees, and well maintained landscaping allow people to see into and across the park, thereby promoting safety and security. All of this is enabled by utilizing a thin structural system, geo-foam, and trenches for trees.

The design was also bold enough to alter the street grid and demolish a freeway overpass to create a more continuous and flexible space. The datum of that street was preserved, however, with a paved path that can be used by vehicles for emergencies, maintenance, and special events. But the Dallas City Council has mused closing the remaining street that bisects the park.

The park has ongoing family-friendly programming and features. Concerts, markets, athletic races, and other events are scheduled throughout the year to make good use of the park. It also has many features that attract a variety of users. There is a modern children’s play area, water fountains, an off-leash dog pen, an outdoor reading room, ping pong tables and mini-golf, and wide lawns. The outdoor seating is plentiful and mobile rather than fixed. And, the entire park is wheelchair accessible.

Klyden Warren Park showcases how commercialization of public space works for the benefit of the public. A restaurant and burger kiosk built onto the lid draw visitors all day and generate funding for maintenance and operations. In another win-win relationship, the Foundation schedules a rotating roster of food trucks to park on the perimeter. The park also gets funding from three local improvement districts.

The park’s $3 million annual budget is managed by a specialized entity that can dedicate time and resources to ensure its success for downtown Dallas. The Woodall Rodgers Park Foundation has event planners, custodians, security staff, and others who manage the park on a daily basis. Along with high foot traffic and good design, the park’s visible staffing helps discourage nuisance activities and ensures litter never piles up. The Foundation’s office is also directly across the street from the park, allowing quick access by staff.

Future lids in Seattle should follow the successful example of Klyde Warren Park. Along with enabling economic activity and a clear design strategy, perhaps the most important finding is that a nonprofit or a dedicated City office needs to manage lid parks on a daily basis. This recommendation is not unique to parks built over freeways and is becoming more common across the country, but the special nature of freeway lids merits a different approach. The management entity would be similar to Friends of Waterfront Seattle and could be an evolution of the Freeway Park Association or the Metropolitan Improvement District.

Case Study: Montlake Lid

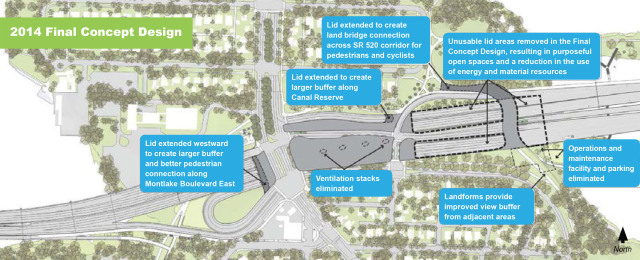

The proposed Montlake Lid in Seattle’s Montlake neighborhood is designed to mitigate the impacts of the SR-520 widening, a $4.6 billion megaproject that includes adding HOV lanes to the freeway, rebuilding the floating bridge across Lake Washington, and rebuilding the Portage Bay Bridge that connects to I-5. Located in a single-family residential area, this lid has a very different context from either Freeway Park or Klyde Warren Park. However, its design process still offers lessons for future lids in Downtown.

Designed by VIA Architecture, the project’s theme is connecting the urban and natural environments. The original design proposed a 1,400-foot long lid stretching from Montlake Boulevard to the edge of Lake Washington. However, it was found that it would impose large walls on the neighboring streets and require significant mechanical ventilation. After another round of public feedback in 2014, the design was shortened to 800 feet, and at the eastern end there will now be a pedestrian and bike bridge across the freeway.

The 2015 concept design (22 MB PDF) shows five lid sections split by multiple roadways. One clear feature will be the relocation of the Montlake Freeway Station to the top of the lid and a transit ramp that will connect buses to the new HOV lanes. Otherwise, the programming is mostly passive and little is emphasized in the concept design beyond multi-use trails and trees. Seattle Neighborhood Greenways is concerned that the plan for the lid and surrounding roadways does not adequately address pedestrian and bicycle mobility.

The lid and land bridge will connect to a new bascule bridge over the nearby Montlake Cut waterway. These will also help reduce local noise and pollution. But otherwise, the conceptual design leaves much to be desired for a major transportation node and urban neighborhood. It is unclear what impacts the lid will have on surrounding land uses, and whether any thought has been given to allowing additional development in proximity that would facilitate better use of this public infrastructure. The lesson is that a clear vision of circulation and programming are needed early on in the design process.

Case Study: Philadelphia

Philadelphia has two lid parks over I-95 near its downtown riverfront. In the course of inventorying lid projects, a local official could only tell me they were completed in 1976 and, together, they are approximately 5.2 acres in size. Because so little information was available, I did not perform a formal case study. However, I had the good fortune to visit Philadelphia after graduating and was able to make some observations.

Built the same year as Freeway Park, these lids were designed more in the flat, open style of Klyde Warren Park. The site plan provides opportunities to meander, sit, play, and explore. They are easily accessible from surrounding streets with clear, wide entryways. Vegetation is well managed and trees are widely spaced to enable views across the park. Active programming wasn’t obvious during my visit, but a variety of paved areas indicated the park spaces were flexible and could host many types of events. On both lids, the freeway traffic below is not noticeable.

Situated in the southern section of the freeway is the larger of the two lid structures. Foglietta Plaza is located between the Dock Street and Spruce Street overpasses (both overpasses are paved with cobblestones, calming traffic speeds). The plaza is surrounded by large trees and a grid of waist-high planters that offer space for sitting. Westward, the plaza seamlessly connects to solid ground, where a Korean War memorial splits Front Street. To the east, the plaza meets Columbus Boulevard at street level. In the southernmost area, across Spruce Street, is the Philadelphia Vietnam Veterans Memorial and a wide walking path.

The smaller “I-95 Park” segment is situated to the north and integrated with the Chestnut Street overpass. Along with lawns, this segment features a dog run and an Irish immigrant memorial. However, the park is accessible only on two sides because of a significant grade change; the eastern side faces Columbus Boulevard with a tall featureless wall. Due to this and other reasons, the nonprofit Delaware River Waterfront Corporation plans to demolish this lid and rebuild it as part of a larger $250 million project to improve public connections to to the river (see the video below). A feasibility study found the new lid can be sloped to provide a view of the river from Front Street.

This example shows how freeway lids can fit into the urban street grid to promote pedestrian connections, mitigate the impacts of freeway traffic, and accommodate a mix of public spaces. The well maintained vegetation and variety of high-quality materials also promote visual interest and civic pride. The design of future lids in Seattle should consider similar opportunities to create an enjoyable park experience.

In an article tomorrow, I will discuss a site analysis and interim solutions for an I-5 lid in Downtown Seattle.

This article is the second installment in a four part series on lidding I-5 in Downtown Seattle. A version of this series originally appeared on The Northwest Urbanist.

Scott Bonjukian has degrees in architecture and planning, and his many interests include neighborhood design, public space and streets, transit systems, pedestrian and bicycle planning, local politics, and natural resource protection. He cross-posts from The Northwest Urbanist and leads the Seattle Lid I-5 effort. He served on The Urbanist board from 2015 to 2018.