Last week, I wrote about the progress of the highway funding bill through Congress. A few politicians—Marco Rubio, John Kasich and Rick Santorum—don’t want to fund highways at the federal level any more, endorsing transportation devolution. I also talked about Chuck Marohn’s Strongtowns no new roads message, which has proven to have some appeal in the urbanist community.

I didn’t delve into the history of we got to the overbuilt highway system we have today. It’s a story of mission creep. President Dwight D. Eisenhower was instrumental in building the Interstate Highway System through the Federal Highway Administration (FHA). The lore goes General Eisenhower was impressed with the efficiency of German autobahn system during World War Two and sought to emulate it in the United States. The catch was Eisenhower didn’t envision plowing highways through major cities. Eric Jaffe tracked down the Eisenhower memorandum detailing his chagrin at highways steamrolling through cities in this City Lab article.

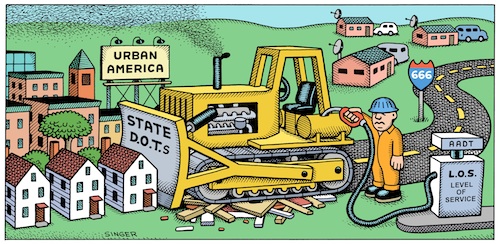

Eisenhower obviously was naive in not anticipating that once he fully unleashed the highway industrial complex, its appetite would grow, and it would set its sights on urban areas. Eisenhower went on to compound his naivete with aloofness while the FHA bulldozed through cities under his nose during his eight years in office. Much like his warning about the military industrial complex, Eisenhower’s warning about the highway industrial complex seems futile, like Dr. Jekyll saying on his way out the door: by the way I’ve created a monster, good luck with that.

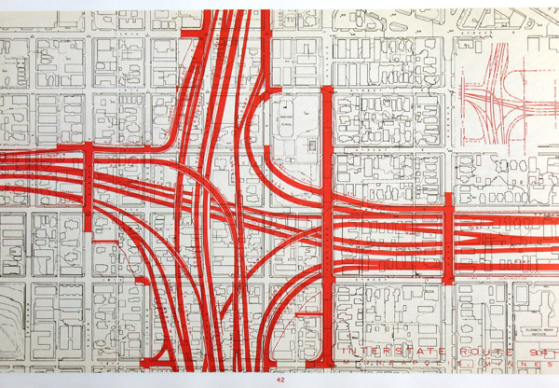

Once the Interstate System was set in motion, the FHA eventually did pave highways through almost every major American city, cementing suburban sprawl growth patterns and hollowing out and sapping the vitality out of vibrant urban neighborhoods. Jaffe estimated 335,000 homes were razed in the first decade of Interstate highway construction alone. Throughout its history, interstates have displaced millions of Americans. Highway planners disproportionately chose to level and pave over neighborhoods with large minority populations. In many cities, they bisected thriving black neighborhoods, hastening their decline and depressing property values.

Redlining and urban highway construction were a one-two punch that did much to impoverish black communities, proving racial oppression wasn’t just a lingering legacy of slavery but also an active ongoing process that continued to tighten the screws on black Americans. Every American generation has found a way to put its own signature on the ongoing saga of racial oppression—segregation, discriminatory voting laws, discriminatory urban “renewal,” neglected urban schools, racial profiling and police brutality—and intermittently pay attention long enough to make some progress.

They may have chosen to level minority communities, but, at least in part, highway engineers’ intentions were good in building urban highways. Speeding interstate travel and making intercity trips more convenient is a noble goal; however, highway expansion in urban areas proved to be misguided. Congestion persisted even as cities sacrificed more and more neighborhoods—and the tax bases along with them—to the chopping block for highways. Each new highway promised to reduce congestion and commute times, but almost universally the promise rang hollow. More highways begat more traffic congestion.

In 1968, mathematician Dietrich Braess formulated what became known as Braess’ paradox: in a congested road network, the addition of a new route will increase overall travel times. Seattle Urban Mobility Plan said the paradox can also be expressed as “the theory that direct routes often function as bottlenecks, and so reductions in total capacity can reduce congestion.” Cities have seen results that support the conclusion. Seoul saw traffic volumes decrease and property values go way up after it demolished Cheonggye Expressway, its downtown highway viaduct, and replaced it with a linear park. Stuttgart, San Francisco, Portland, New York, and Milwaukee have seen similar results when tearing down urban freeways.

Recently, Amherst professor Anna Nigurney argued the Braess paradox stops applying at sufficiently high congestion levels and a new route will have no effect on travel times, which is almost as damning and undercuts the justification for expanding urban highway infrastructure. Nigurney’s findings bolster the case against highway expansion, as Lisa Zyga explains:

In a sense, the negation of the paradox actually adds to the paradox’s original conclusions: when designing transportation networks (and other kinds of networks), extreme caution should be used in adding new routes, since at worst the new routes will slow travelers down, and at best, the new routes won’t even be used.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.