Crosscut recently published a piece by Eric Scigliano exalting the importance of urban tree canopy while decrying density as the “mortal enemy of trees.” The piece was novel in its use of environmental values to discourage one of the single greatest tools we have in promoting sustainability: dense, urban living. And while most of this piece will examine what the author got wrong, there’s plenty he got right.

To begin, tree preservation is a worthy goal. Indeed, urban canopy has a range of benefits for cities, including: cleaning the air, cooling the air, sequestering carbon, enhancing livability, promoting mental and emotional health, and absorbing rainwater. Even NASA thinks you should live on a tree-lined street.

We in the Pacific Northwest pride ourselves on our natural greenery — placing the mighty evergreen front and center on the Cascadian flag. On warm summer days, we flock to the mountains to hike among the coniferous giants that cover our hills. “Seattleites,” remarked a friend returning from DC, “look like they’re either in a band you’ve never heard of or fresh off the REI discount rack — ready for a hike at a moments notice.”

So when someone threatens our trees, they threaten our regional identity and way of life.

But in Scigliano’s call to preserve the landscaping of single-family homes, he misses the forest for the trees.

First, Scigliano presents us with a false choice between growth and protecting our urban canopy. He cites findings from American Forests that show Seattle’s tree canopy grew from 10% in 1996 to 28.5% in 2012. Our population grew 23% over the same period. Correlation by no means implies causation, but Seattle has shown that substantial population growth and tree canopy expansion aren’t mutually exclusive.

Indeed, there appears to be little correlation between population density and urban tree canopy. According to one source, Los Angeles has similar population density (8,282/sq mi vs 7,969/sq mi) and just 18% tree canopy. New York City, meanwhile, has more than three times our population density (2,7857/sq mi) but virtually ties us at 24% tree canopy. To be fair, tree canopy is notoriously hard to measure. It can also change quickly over time, as Seattle has shown. But if the home of Manhattan can match our tree canopy, there’s no reason to fear a few new townhomes in our neighborhoods.

In fact, there’s much more to fear from capping growth in the city. People are moving to the region whether Seattle makes room for them or not. But if they don’t move here, they’ll be pushed to the suburbs and exurbs, fueling deforestation as sprawl expands into our meadows and foothills, replacing natural beauty with low density residential subdivision developments and strip malls.

Instead, we should want people to move to the city, where their carbon footprint and energy usage will be dramatically lower. One recent study by UC Berkeley suggests that suburbs effectively cancel out the climate benefits of dense, urban areas. Another by the University of Toronto suggests that as populations grow, regional emissions decline. Dense living is efficient living. Residents share amenities and resources. Multi-unit buildings share walls, preventing heat loss. Walkable and bikable neighborhoods encourage people to leave their cars at home.

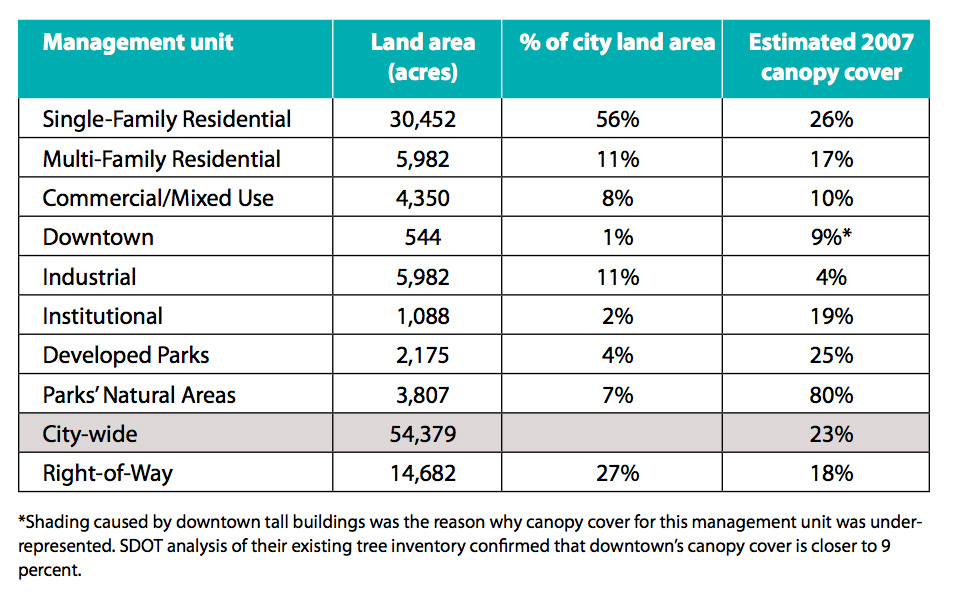

Maintaining a development pattern primarily of single-family homes is no way to maintain our urban canopy or our environment. With only one-third of urban canopy growing in single-family lots, suggesting otherwise was always a false start. Instead, we should be looking at smart design guidelines to incorporate trees in new development and public spaces, and improve the health of existing stock (especially those in parks and greenbelts). We should also push for a sustainability agenda that’s broader than tree coverage, like rigorous housing standards, robust and reliable public transportation, and recommendations for inclusive, affordable growth.

Ben Crowther

Ben is a Seattle area native, living with his husband downtown since 2013. He started in queer grassroots organizing in 2009 and quickly developed a love for all things political and wonky. When he’s not reading news articles, he can be found excitedly pointing out new buses or prime plots for redevelopment to his uninterested friends who really just want to get to dinner. Ben served as The Urbanist's Policy and Legislative Affairs Director from 2015 to 2018 and primarily writes about political issues.