Like many desirable and economically strong coastal cities Seattle is experiencing rapidly rising rents. The Housing Affordability and Livability Agenda (HALA) committee understands part of the problem is that current zoning unreasonably restricts supply and is therefore proposing a significant increase in development capacity through rezoning. While the move is highly progressive, I believe that the proposed increases fall short of actual demand and unnecessarily diminish the return that future transportation investments will deliver in the urban villages. Let’s see why.

First, let’s understand what happens in the center of an urban village. In Ballard, for example, demand is already very high. Most if not all new development is built to the height limit and despite the fact that all the zoned space is used, there is still sufficient pent-up demand that new developments can start quickly and still be built to the height limit. The result of this is that new development is quickly consuming the available developable spaces and all at a constant level of density, as if demand is the same for every block.

It is likely that Ballard will get access to light rail within the next 10 to 15 years. The buildings in the urban village center, however, built in this era, are likely to last 30 years or more before being redeveloped, and are mostly 6 to 8 floors with potentially a few in the 12-floor range if the HALA Grand Bargain goes through. This means that we are setting a maximum cap today on the number of people who can live within a short walk of a light rail station and would:

- Reduce congestion;

- Reduce pollution and contribute less to climate change; and

- Take part of our growing economy, rather than being priced out to the furthest part of the city or another city altogether.

This artificial cap should be well understood. In 10 years, we may see that we continue to have strong demand in a walkable amenity-filled neighborhood like Ballard (why wouldn’t we?) and we can increase height limits in the area, but as most lots would already be redeveloped, that upzone will have a greatly diminished effect.

Alternatively, we can let the market decide how to best meet demand in the center of the neighborhood. The demand today will not be as high as the demand in 10 years, but given that every development hits upon the height limit and new developments come quickly thereafter, if we let the market decide the concentration of housing supply, it is likely that today’s demand will be served in a more compact area around the center of the neighborhood. In turn, this will leave more lots closer to the center developable in the future. The cumulative result will be to allow a lot more people to live within walking distance of a future light rail station and let the neighborhood reap all the benefits that this brings.

Another way to look at it is to compare Seattle to other cities with similar population growth, but a more market-driven approach. Between 2006 and 2011, Seattle grew by 6.7% while Vancouver, BC grew by 4.4%. Demand is, in fact, stronger in Seattle. When Vancouver opened the Canada Line Skytrain line in 2009, it increased height limits in the areas around stations. One such station is Marine Drive (all buildings in photo still under construction):

Marine Drive station is 13 minutes from the first downtown station, about as much as some estimates for Ballard-Downtown LRT. It was not an urban center before the neighorhood zoning went into effect, yet in a city with a lower growth rate than Seattle there is still sufficient demand for developers to build 30- to 40-floor buildings, rather than 6 to 8 as we have decided in Seattle.

If Vancouver can serve as a litmus test for whether Seattle’s zoning allows housing supply to meet demand, then the result will be that Seattle’s zoning (and HALA proposals) is grossly insufficient to allow supply to meet demand and it is locking land use patterns in this mode for 30 years in the future or more.

But Vancouver is no exception. The same pattern of high density near rail stations is prevalent in large European and Asian cities. It’s a no-brainer, really — if a city is to invest significantly in high capacity transit it, then it wants to derive the maximum value out of it.

The best bet for Seattle to ensure it slows rapid rent increases and maximizes the future return on transportation investments is to be open to denser projects in the center of urban villages. This can mean relaxing height limits based on demand projections coming not only from planning agencies but also from the development community, which after all expends great effort to model and understand demand. Let’s not forget that bigger projects would also deliver more commercial linkage tax to the City, which would enable it to build out subsidized and effectively rent-stabilized housing in addition to the market-based supply. HALA is on the right track, but it needs to go a little further.

When people think of Europe, they usually think of historic blocks of 6-floor buildings, but Europe is not shy of building dense high-rise neighborhoods next to rail stations.

As already mentioned, one of the benefits of not restraining building heights as strongly is that fewer lots are developed. This naturally means that more historic and old buildings are preserved. Such buildings provide naturally affordable housing, business space, and are often home to long-term residents. They also provide crucial diversity which activates the streets of a neighborhood. So, counter to popular discussions, lowering restrictions on building supply actually preserves more of the “soul” of a neighborhood and lowers displacement. This works great in tandem with subsidized housing built as a result of the commercial linkage tax and can lead to a net increase in affordable housing.

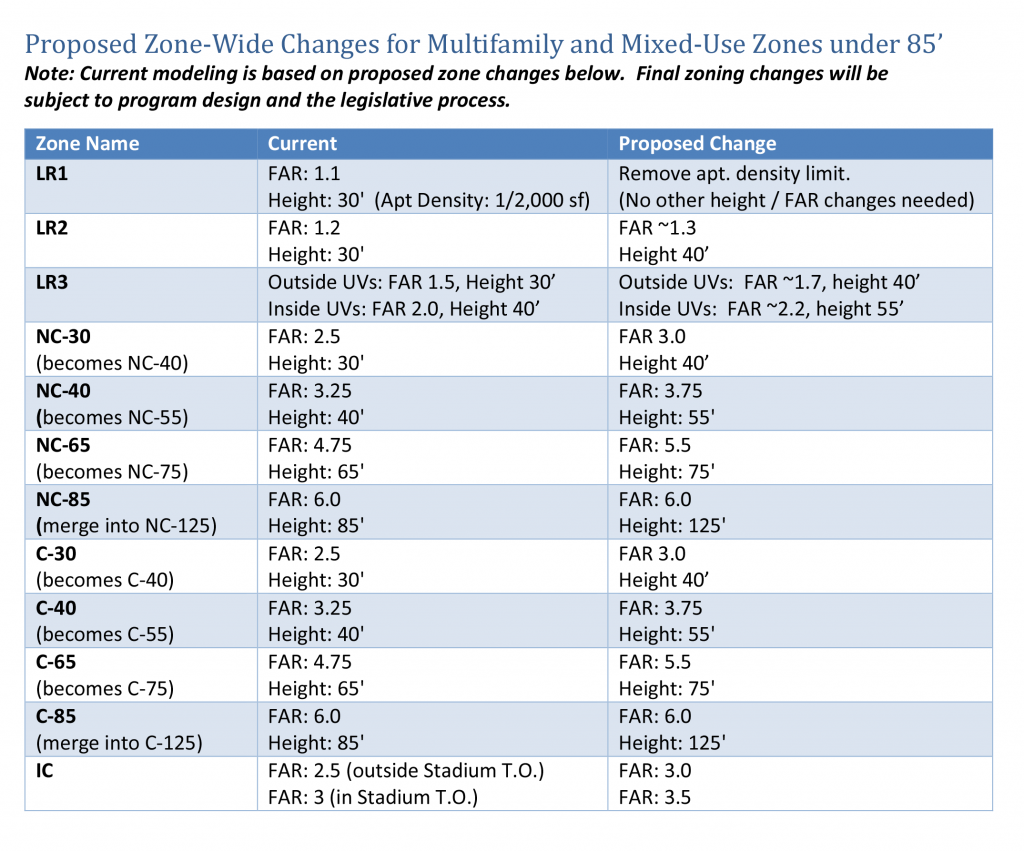

The HALA Grand Bargain will see heights increase in urban villages, but increase amounts to an average of no more than one-third only:

This is a great step in the right direction, but an increase of one-third is inadequate if the examples from other parts of the world are to be considered. On November 9th, the Seattle City Council will vote on the HALA policies. Let them know you support the HALA recommendations and would like to see an even more significant relaxation of restrictions on the heights of buildings with the aim to maximize future benefits from light rail investments, slow down rent increases, and increase the net amount of affordable housing.

Anton Babadjanov

Anton has been living in the Pacific Northwest since 2005 and in Seattle since 2011. While building technology products during the day, his passion for urban planning and transportation is no less and stems from a childhood of growing up in the urban core of a small European city.