After reading Kristin Ohlson’s The Soil Will Save Us, I was tempted to pack up and head for the countryside to become an organic farmer. The promise of restorative no-till agriculture is so great that it could fully offset all human sources of carbon emissions with as little as 11% of the world’s cropland, at least according to one pair of researchers in New Mexico that Ohlson referenced. So I thought trade the smog and the corruption of the city for the fresher, if manure-tinged, country air and be part of the solution. I didn’t go through with my bucolic daydream — guess I’m just too set in my wicked city ways and being bathed in a neon street sign glow. Even in cities, though, restorative agriculture principles can be applied — whether in parks, urban farms, or home gardens — to improve the health of the soil and sequester carbon from the air.

How Soil Captures Carbon

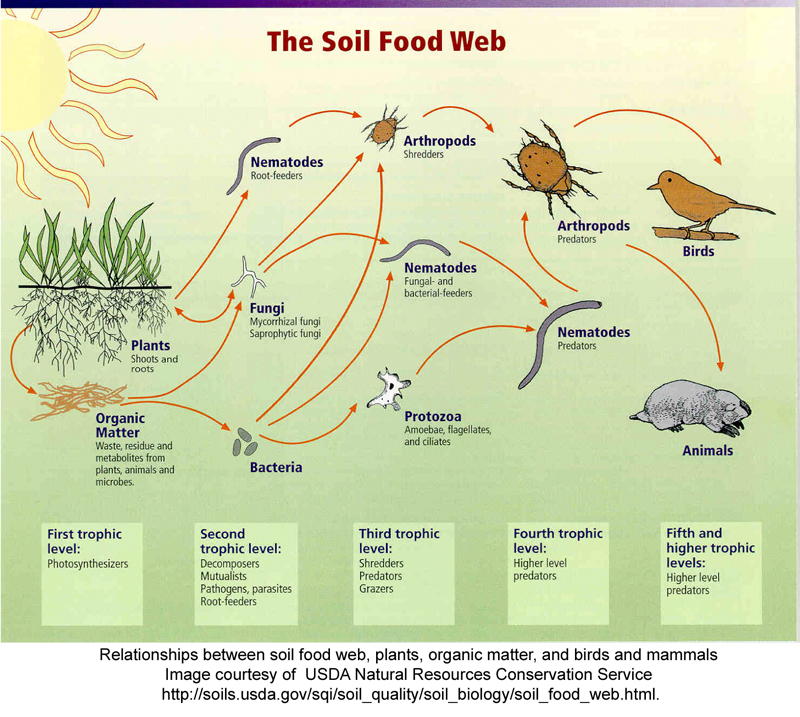

The soil is little understood which is part of the reason why it’s overlooked as a solution to climate change. The key to capturing carbon is the vibrant ecosystem of microorganisms that builds up around root structures in healthy organic soil. A healthy soil ecosystem builds up carbon-rich humus. Roots exude sugars into the soil to attract microorganisms that process the sugar and leave nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus in return. The symbiotic relationships get very complex, building up humus in the process. The result is that the soil organisms lock away the carbon that plants have drawn from the atmosphere via photosynthesis, thereby counterattacking the greenhouse effect.

Another soil writer, Courtney White (author of Grass, Soil, Hope), explains “soils contain about three times the amount of carbon that’s stored in vegetation and twice the amount stored in the atmosphere. Since two-thirds of the earth’s land mass is grassland, additional CO2 storage in the soil via better management practices, even on a small scale, could have a huge impact.” The soil is a huge part of the equilibrium that until recently had existed as carbon cycled through the atmosphere, the oceans, the flora and fauna (i.e. life above ground), and the soil (i.e life below ground). Our carbon imbalance not only warms the planet and destabilizes weather patterns, it also contributes to ocean acidification since an estimated 30% to 40% of anthropogenic carbon dioxide dissolves into oceans, rivers and lakes and lowers their pH level.

Under industrial farming techniques, little carbon is captured in the soil. Chemical fertilizers co-opt the micro-organisms that normally trade nutrients for sugars from the roots in the soil. Herbicides, fungicides, and pesticides stifle the biodiversity not only above ground but below it in the soil, further limiting its carbon capturing capacity. The combine’s plows disrupt any micro-organism networks that did manage to survive the chemical bath. The result is soil with alarmingly low carbon content. Relative to healthy soil, it’s inert and lifeless. Industrialized farming took the soil depleting techniques to the next level, but ever since humans began plowing their fields, they’ve been damaging the soil carbon beneath their feet.

Interestingly, the first spike in anthropogenic carbon emissions predates the industrial revolution and goes back to the agricultural revolution and the advent of the plow, the widespread adoption to mono-cropping, and deforestation to make way for these new farms. “Thousands of years of poor farming and ranching practices — and, especially, modern industrial agriculture — have led to the loss of up to 80 percent of carbon from the world’s soils,” Ohlson writes. The switch to extractive farming depleted soil carbon and unleashed it into the air, and moreover it also damaged some land beyond productive use. Part of the reason the fertile crescent in the Middle East today is largely desert is because farmers unwittingly contributed to desertification through their overgrazing and overfarming that depleted the soil. Shifts in climate also share some blame, but regenerative farmers have shown soil-carbon rich fields can thrive even in dry conditions that would cause conventional farms to fail. This first piece of the puzzle in understanding greenhouse gases is largely overlooked, but I think therein lies one part of the solution. Obviously using regenerative farming to capture carbon is not to give carte blanche to fossil fuel burning. But cutting back marginally on emissions alone isn’t a solution. It’s controlled decline.

Rising Oceans

It’s in cities’ self interest to take the lead in limiting global warming. In fact, some cities’ very survival depends on halting global warming (I’m looking at you, Miami). Rising oceans imperil coastal cities around the world — Seattle included. Eight of the world’s ten largest cities are on the coast. Global warming causes oceans to rise through a double whammy of melting glaciers and ice sheets and thermal expansion (the ocean takes on greater volume at higher temperatures). So far the process has been relatively gradual. The ocean has risen about eight inches in the last century. However, the pace is accelerating and it might not continue to be so gradual if say a giant glacier in Greenland suddenly plunged into the Atlantic Ocean. The Jakobshavn glacier alone contains enough water to raise the ocean by at least a foot, and it appears to be deteriorating and slipping into the sea. The Greenland Ice Sheet in sum contains enough water to raise the ocean by 20 feet while the imperiled glaciers of West Antarctica contain more than that.

In 2012, the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) predicted the ocean would rise by between 11 and 38 inches by the year 2100 — already enough to be quite a problem — but they didn’t factor in land ice such as the Greenland Ice Sheet. In August, NASA scientists issued a statement saying the IPCC estimates were too conservative and suggesting the ocean will rise much more than predicted. In other words, we aren’t doing enough to stop the rise in atmospheric carbon. We’ve been burying our heads in the sand and hiding behind the hope we’ve got the science wrong and this problem isn’t so big and maybe will go away.

Reversing the Warming Trend

The benefit of the restorative agriculture approach is that it actively takes carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere. Implemented on a large enough scale, it could potentially not just offset carbon emissions, but actually decrease the amount of carbon in the atmosphere. We passed the 400 parts per million carbon threshold in 2013 for the first time in 3 million years and the carbon emissions haven’t let up. There is already enough carbon in the air to continue the warming pattern for centuries even if emissions stabilized. Carbon sequestration could help us return to a safer level and snap out of the warming pattern before the ocean rise too high. Soil carbon is the most practical, sustainable, and affordable way we have to sequester carbon.

Switching even a tenth of cropland to restorative techniques would require a huge paradigm shift from the industrial mono-cropping that predominates. Restorative agriculture advocates will have a hard time winning over the “nozzle heads,” a term for conventional farmers always looking to apply petroleum-based fertilizer, pesticides, or herbicides from the nozzle of their applicators in search of short term profits. Ohlson reports that restorative farming can be more profitable than conventional farming since, unlike nozzle heads, no-till organic farmers do not require expensive chemical inputs from the likes of Monsanto. We aren’t asking farmers to be martyrs to global warming. That can make healthy profits from healthy soil producing organic food using regenerative techniques.

Some cap and trade climate plans would further compensate farmers for sequestering carbon with direct payments. However, implementation gets extremely complicated. To make a carbon credit trading system work, you’d have to establish a baseline of carbon in the soil and then demonstrate how much additional carbon you were able to capture to earn the credits. Measuring the soil carbon isn’t easy. Conventional techniques included sterilizing the soil in a kiln before measuring which had the drawback of burning off some of the carbon. Luckily, some regenerative minded soil scientists came up with a better technique. You’d still have take many samples because the soil carbon levels can vary widely in different points within one plot. It becomes a bit of bureaucratic nightmare then to set up an exhaustive carbon monitoring regime that would probably be required before cold hard cash is handed out in the form of carbon credits to these diligent farmers. And, ironically, the soil regenerating pioneers like Gabe Brown might not benefit as much from a carbon credit system since they’ve already significantly boosted the carbon in their soil and their starting carbon baselines will be much higher.

Stormwater Management

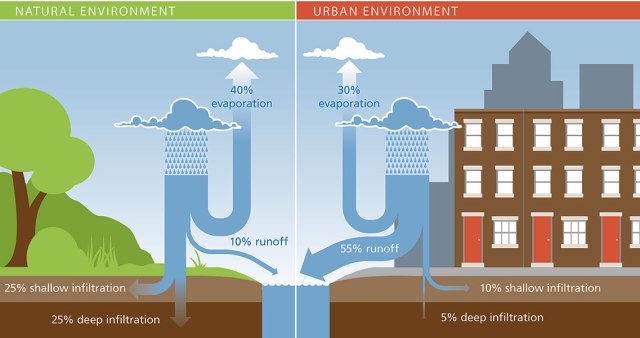

Climate change also threatens cities with intensified droughts and floods. High carbon soil is much more resilient. It’s able to lock moisture away longer in times of drought; cover crops dampen the scorching sun and prevent the soil from being blown away. During times of flood, high carbon soil can absorb more runoff and is much less likely to be washed away. The resiliency and absorbency of the soil can be a huge and bankable asset for cities. Sewer systems are a huge expense. Philadelphia received accolades for its green stormwater management plan that saved the city the expense of adding storm sewer capacity by greening the riverfront to reduce demand. Other cities are following Philadelphia’s lead and restorative land management could amplify those efforts by capturing more carbon and make the soil even more absorbent and healthy.

The virtuous cycle green management techniques foster isn’t well documented, but Philadelphia has found many perks: “The widespread implementation of green stormwater infrastructure also promises what city officials like to tout as a ‘triple win’ for Philadelphia: a cleaner environment; cost-effective stormwater solutions that provide jobs for local people; and a social fabric reinforced by better neighborhood parks and public spaces. Another benefit is that unlike pipes known only by engineers, many elements of green infrastructure can be seen and tended by the entire community.” This is also what restorative agriculture looks like in an urban setting.

Using healthy bio-diverse soil to retain stormwater not only helps the sewer system, it should also help replenish aquifers that are being depleted in many highly paved urban and suburban environments dotted with the thirsty green lawns integral to the suburban experience. In my home state of Minnesota, many cities are dealing with aquifer depletion. A prominent lake in the northwest metro of the Twin Cities, White Bear Lake, has dropped 6 feet as the area has drank greedily from Prairie du Chien-Jordan aquifer that feeds the lake. Some lakes have lost ten feet in a decade. Obviously those cities are not on a sustainable course for water use, and their story is all too common. Cities like Wichita, Kansas on the heavily depleted Ogallala aquifer are approaching chronic water shortages as their wells dry up.

Healthy carbon rich soil at least allows an ecosystem to make the most of the precipitation that it gets, and more water will find its way trickling down to an aquifer rather than flushed into a storm drain and washed down the nearest river carrying a lot of soil nutrients with it. It doesn’t do away with the need for more sustainable water use, but it does given the aquifer a better chance of keeping up with modern civilization’s voracious appetite for fossil water.

Let Your Lawn Grow Wild

Cities are not all concrete and glass, and some, like Seattle, are quite green and teeming with life actually. Take a walk around a Seattle neighborhood and you will find some epic gardens where a boring plot of grass might normally reside. Some even have “Rain Wise” lawn signs showing the homeowners were aware of the ecological benefits of their garden. There are many reasons why people turn their yards into vibrant gardens. Some are interested in pollinator pathways in times of bee colony collapse. Bird-watchers hope to attract an interesting avian species into their midst. Others just prefer the aesthetic appeal of a garden to a blob of green. Shy residents like the privacy a row of towering shrubs, plants ,and trees provide. Add to that list doing your own small part to sequester carbon because organic gardening makes the most of these small urban plots and puts more carbon in the soil. This isn’t to totally vilify lawns. Even a closely cropped lawn can have a vast root structure that can support the soil organisms beneath. However, generally the greater the diversity above the ground, the greater the diversity in the soil.

Apartments are getting into the act, too, as more and more add green roofs and gardens on their roofs and balconies. The amount of carbon these green roofs can capture is likely limited by their depth. Typically they don’t seem to be more than a foot or two deep. At ground level, roots can penetrate much deeper and bring dense network of soil organisms down with them. We could build deeper green roofs to magnify their carbon capturing capabilities, not to mention their insulating quality and ability to support large plants or trees. Even shallow green roofs help cities combat climate change. At the very least they replace a highly heat absorbent material such as concrete with something green and less absorbent, decreasing the urban heat island effect.

Sustainably Grazing Urban Grassland

One of the most shocking and counter-intuitive revelations of Ohlson’s book was that the best way to manage grasslands from a soil health perspective is to periodically graze a small plot with a veritable stampede of cattle tenderizing the ground with their hooves and depositing a deluge of manure to wake up the soil microorganisms and set them to work on the cowpie buffet. Conventionally free range cattle are given a large pasture to nibble at on their leisure. This allows cows to target their favorite particular grass species which they gobble down to the roots. Confined on a smaller plot and competing with the whole herd, a cow will be less picky and is less likely to greedily eat its favorite plant to the root. The herd is moved on to the next small plot and the trampled, manure-laden and urine-soaked field they left will spring back to life, with a juggernaut of microorganism activity unleashed in the soil spurring on a great diversity of life.

Cities are limited in how much regenerative grazing its citizens will tolerate in their midst. Obviously, some people don’t like having any livestock in their neighborhood, let alone a large herd depositing a large amount of manure which is ideal from soil health perspective. Perhaps attitudes will change. Since intensive grazing need only happen sporadically, it might be thought of as a temporary annoyance comparable to street sweeping days. Cities contain spaces where sustainable grazing might be very productive. Freeways are often lined with with buffers of grass in the median and along the ditches. These spaces are neglected save for a guy who comes by in a tractor a few times a year to mow and the occasional errant motorist. Perhaps, these grasses could be managed to boost soil carbon and a herd of livestock could come through periodically in place of the lawnmower.

It seems the logical extension of the “Rent a Ruminant” goat herd for hire business that gained notoriety when it joined Amazon Service (meaning there’s an app for renting goats now.) Mostly these goats clear unwanted blackberry bushes, apparently, but unintentionally they may have given soil organisms a boost with the manure they have left behind, especially compared to the pounding the soil would take in the alternative of clearing the bushes with heavy machinery or herbicide. Maybe these goat herds could also be conscripted as part of a plan to boost soil carbon in city parkland. The goat might be a better match for urban land management that their bulkier bovine cousins, but either way it’s better than using heavy equipment and chemicals.

Also note that since the best method for grassland management seems to involve intensive livestock grazing, a sliver of an opening exists for carnivores seeking to ecologically justify their appetite for meat. Industrial livestock raising is still pretty indefensible, but livestock certified as sustainably raised via regenerative ranching could have a place in future diets and provide a generous source of income for the responsible ranchers that treat their livestock and soil well. It would be difficult to convert every human to vegetarianism but making sure we are raising animals using sustainable methods that give back to the soil would be a huge step forward. It’s a glimmer of hope, albeit possibly a mirage in the larger moral framework, to assuage the guilt of this omnivore.

Compost Haste

Ohlson was critical of the compost that large-scale composting programs produce, saying that much of it decays anaerobically, essentially ferments, and worse the potent greenhouse gas methane can be a byproduct. Good compost’s big benefit, she argues, is that it introduces microorganisms into the soil that stimulate more soil organism activity. A putrefied slop of food scraps and lawn clippings don’t cut it. A good compost pile needs to be tended carefully, layered with green and brown organic materials, rotated, and left open to the air to allow aerobic decay, which isn’t necessarily easy to do on a huge scale. Unlike anaerobic compost, good aerobic compost produces high enough temperatures to destroy pathogens. I expect Seattle’s compost program doesn’t produce the world’s best compost but it’s better than the organic waste ending up incinerated (which would release carbon dioxide) or in a landfill (which would release methane).

As regenerative agriculture takes off, local practitioners could advise the city on what kind of compost would be most beneficial for their soil and we can adjust the compost program to seek to produce it. Part of issue is that in a apartment building like ours compost sits in a bin in the garage for nearly a week before it’s picked up — time it could have been aerobically composting rather than putrefying. The city’s vendor, Cedar Grove Composting, struggles at times to make a usable compost material from the assortment of refuse they receive, not all of it organic. (Don’t throw plastic in with compost please.)

Composting is mandatory in Seattle and scofflaws can be shamed with stickers on their bins and fined. It’s probably a necessary step since the EPA estimate Americans compost only 3% of their food waste. Compost done well could be both food and catalyst for the soil organisms we are trying to grow under our feet to eat the carbon byproduct of our twin filthy habits of burning fossil fuel and practicing industrial agriculture.

Overcoming Big Ag Orthodoxy

The problem with switching to restorative agriculture is that the model of industrial farming is extremely entrenched and supported by enormous influence both in Washington, D.C. and at the universities where agricultural research is conducted. Big Ag literally holds the purse strings in many universities’ agriculture programs and research has to toe the company line to get funded. Ohlson’s final chapter does an excellent job of documenting Big Ag lobbying power in D.C. and their infiltration of the universities that should be conducting unbiased research rather than acting as the government subsidized research and development arms of corporations.

Thanks to Big Ag’s lobbying muscle, the Farm Bill is tilted heavily toward industrial farming and trying to even the playing field for small scale regenerative farmers and ranchers should be priority in lieu of a program that actively promotes regenerative techniques and perhaps rewards farmers for boosting the carbon in their soil.

Despite Big Ag hegemony the demand for organic food is high, but not all organic food is created equally. Some organic food still relies heavily on industrial techniques on plowed land. Most organic farmers don’t actively try to raise their soil carbon, but perhaps we can find a way to certify those who do and see if consumers would prefer this doubly organic sustainable food. In this way, urban consumers can influence farming practices in their rural surroundings and perhaps even draw more small-scale agriculture near the city center.

Conclusion

This got to be a long rambling piece, but I think there is much cities can do to combat global warming on a variety levels. Regenerative agriculture is a new frontier in carbon sequestration and sustainable land management. Urbanites don’t have to leave in exodus for the agricultural hinterland to apply these principles to improve the health of the soil around them and in the process pull carbon out of the atmosphere. Homeowners can turn their yards into gardens rich with life above and below the surface by just being a bit more conscientious and diligent gardeners. Apartment dwellers can rent a garden plot on their roof and nurture it into a thriving mini ecosystem or grow some plants on a balcony or window seal.

From a fossil fuel standpoint, urban living is less carbon intensive than the suburban lifestyle thanks to shorter commutes, higher transit use, and lower heating costs per resident. From a soil carbon standpoint, urbanites can also take the lead by providing a market for organic food grown using regenerative methods, composting well, maximizing the soil health in their yards, gardens and green roofs, and demanding their governments manage public lands sustainably with eye toward capturing soil carbon.

This is a cross-post and originally appeared on The Puget Sound and The Fury.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.