People call me the n-word when they like me, and ‘white boy’ when they don’t. He calls me both, and he’s always happy to see me.

This Michael’s last name really is Jackson, a fellow in his twenties who makes full use of the excellent napping opportunities the long 7/49 route provides. Sometimes after dozing off a while he’ll simply watch me work with the folks, smiling to himself.

“Be blessed tonight. Every night!” he calls out to his friends, who’ve just yelled a thanks to me.

At the Henderson layover now, he’s showing me photographs on his flip phone. He knows I like photography (this was before the ad about me which proclaims that fact, causing people to come up to me, ask if I like photography, and then immediately step away, as if that were a terrible thing!). Michael’s pictures are pretty good. Here’s one pointed directly at the sun, as Akira Kurosawa first intrepidly did in 1950’s Rashamon. Another one has an emphasis on spatial dimension a la Sergio Leone, with objects situated near and very far from the picture plane. Here’s another which clips the heads, letting us only see the subject’s mouths, not unlike the opening moments in Malick’s 2011 Tree of Life. I sum all of that critique into one word: “tight,” I say aloud, expanding a little further.

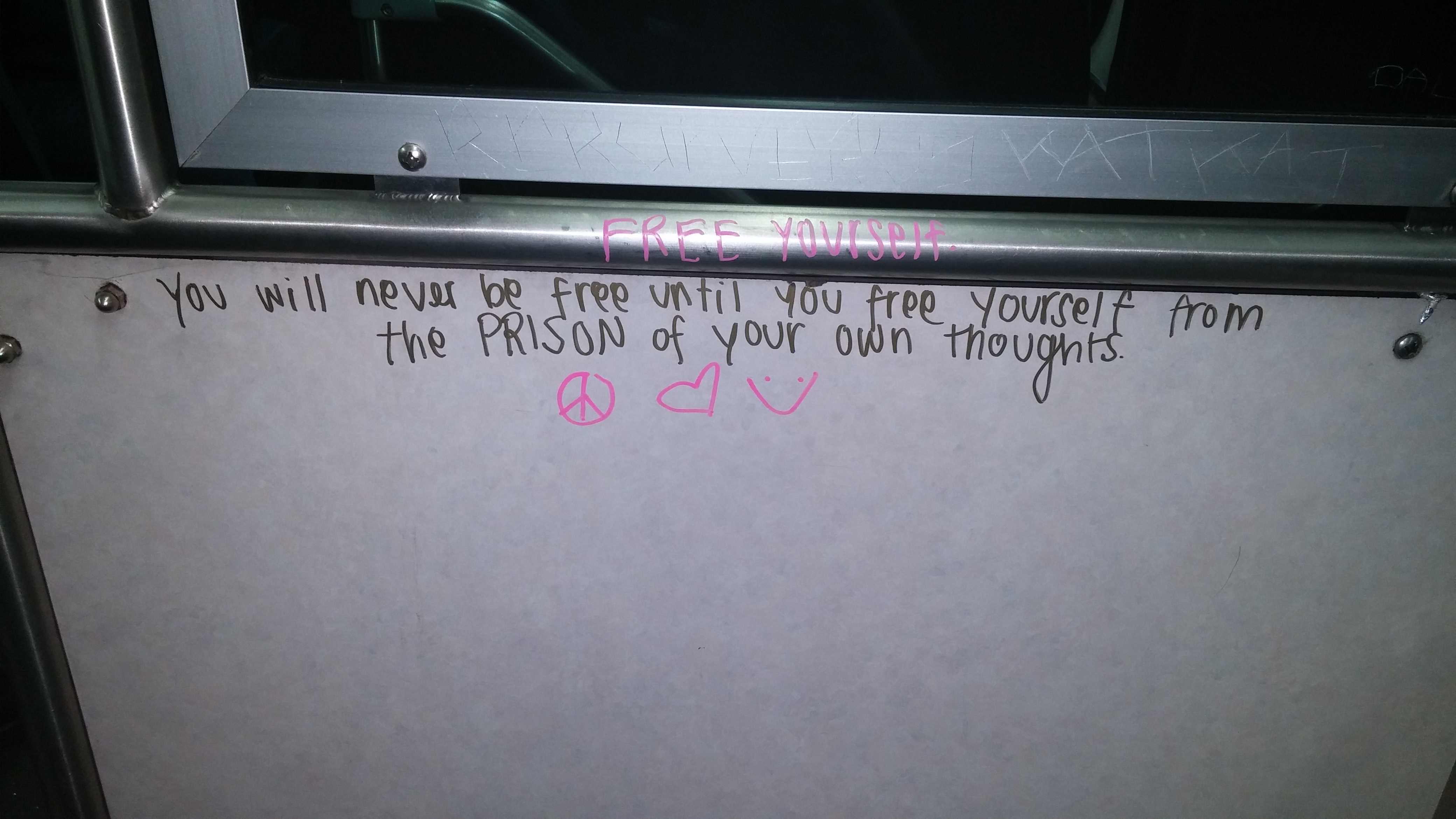

“Man, you’re just fuckin’ the best.” He asks permission, then takes a picture of me. This is the third such event tonight. Earlier a piano playing girl was excited, and before that I’d asked some men in the back to photograph some graffiti I liked and email it to me. I don’t have a camera on my phone, and the graffiti, pictured above, touched my heart. One of those situations where you ask, “excuse me guys, this is gonna sound really weird, but….” I’m glad they were amenable. We have an earth to share, and we may as well get along.

Michael continues enthusing. “You’re always sayin’ shit, sayin’ hi, and even though they angry at first they be like ‘hi!’ Fuckin’ treatin’ people good and shit.” His is a wide-bodied grin glowing for days. He shakes his head in aw-shucks wonder, like you do when your favorite player tosses in a three-pointer, no big deal. “I see you talkin’ into the microphone, I’m like ‘that’s my dude!’ You’re great.”

All I can do in the face of such praise is turn it around. Sincerely, I say, “well, thank you for smiling, for always–”

“That’s my nickname, you said it!”

“What, smiling?”

“Smiley!”

“Nice! That’s’ beautiful thing you’re doin,’ smiling. I know you’re positive ’cause I remember the day of the Super Bowl, after we lost the game, and you were still happy, talking ’bout how it was a good game, well-played game, good football. Whole rest o’ the city’s cryin,’ you’re talkin’ about it was good football….”

He details how he watched the game at a bar on Rainier Avenue with– not friends or family, but a local police officer. Both were extremely curious about the game, and decided to step off the street and spend some time together. Michael described the ebullient nature of such solidarity, a sharing of life so unexpected it makes you just about blow up with well-being, the possibilities of goodness all around you becoming realized. It could be like this. It’s like this, right now. I know how he felt; I was once in an abandoned barn in Eastern Washington making photographs, way out on those vast and unbodied plains. The officer who accosted me on scene provided me with what can only be called the greatest civilian-officer experience I’ve ever had. He actually presumed I was innocent. He was genuinely checking in to ensure I was doing all right. We talked about good nearby photo locations, and how a lot of Japanese tourists have been through here, how he was surprised by how much they liked photographing things like empty barns and wheat stalks. I wanted to hug the guy.

“Iss bout bein’ positive,” Michael sighs. Pawsitive. “Niggers actin’ all hard and shit, forget how to enjoy life.” The Dalai Lama might use different vocabulary, but the two of them would be politely nodding in agreement were they both here; who can forget the Dalai Lama’s wonderful thought, phrased to perfect succinction: “choose optimism– it feels better!”

“You a cool ass white boy, man,” he continues. “You a cool ass white boy, doin’ your thing. Don’t stop!”

“You too, man, you too.” I’m referring to his resilient attitude and his ability to see all that is light, whether cool or uncool. “Stay happy!”

“You too. Hey, be blessed, be safe!”

“And you also! Be blessed, be safe!”

“Hey!” He pauses for dramatic effect, and with a grin christens me with a new name: “Nigger Nate!”

“Ha! Always!”

Nathan Vass is an artist, filmmaker, photographer, and author by day, and a Metro bus driver by night, where his community-building work has been showcased on TED, NPR, The Seattle Times, KING 5 and landed him a spot on Seattle Magazine’s 2018 list of the 35 Most Influential People in Seattle. He has shown in over forty photography shows is also the director of nine films, six of which have shown at festivals, and one of which premiered at Henry Art Gallery. His book, The Lines That Make Us, is a Seattle bestseller and 2019 WA State Book Awards finalist.