Lane width helps to control speed on urban streets. People driving tend to slow when streets are narrow.

Urban Streets

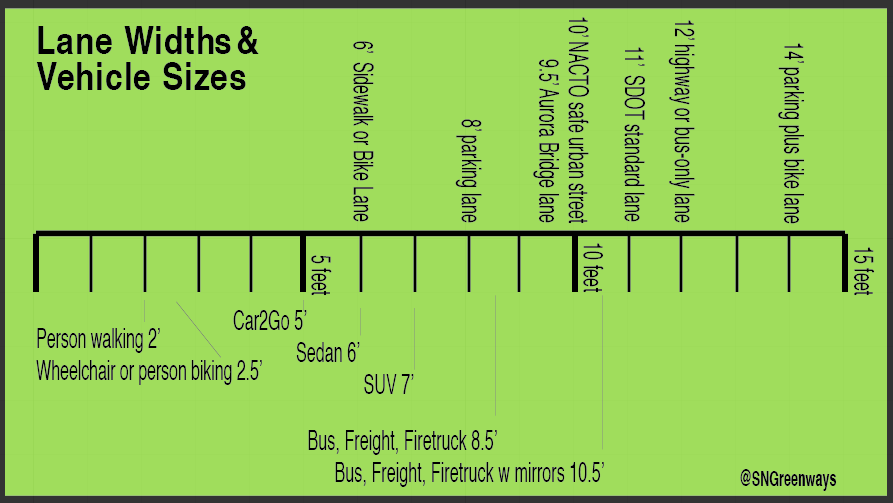

The National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO) recommends a default of 10-foot lanes.

“Lane widths of 10 feet are appropriate in urban areas and have a positive impact on a street’s safety without impacting traffic operations. For designated truck or transit routes, one travel lane of 11 feet may be used in each direction. In select cases, narrower travel lanes (9–9.5 feet) can be effective as through lanes in conjunction with a turn lane.”

Seattle’s current standard is 11-foot lanes and 12-foot bus-only lanes. Many of our streets were laid out in a time when wider was always better — and ended up with dangerously wide lanes, dangerous because wide lanes encourage people to drive fast, and when cars go faster, collisions do more harm. Narrower lanes in urban areas are shown to result in less aggressive driving, and give drivers more ability to slow or stop their vehicles over a short distance to avoid collision.

While tooling along city streets, unless you are a transportation engineer, you aren’t aware of street width.

While tooling along city streets, unless you are a transportation engineer, you aren’t aware of street width.

You aren’t thinking, “Hey, I’m in a 14-foot lane. And now I’m in a nine-foot lane. And now I’m in a 10-foot lane.” (Note, transportation engineers really do think like this.)

Instead, you, the average mortal, just thinks (if you are driving a car), “I can go fast here. Whoa! This street is narrow, I’d better slow down. And now I can speed up a bit again.”

Seattle’s standard width for parked car lanes is eight feet wide, while adding a bike lane that avoids the “door zone” (the distance a car driver can accidentally fling open a door into the path of an oncoming person on a bike) requires a a 14-foot lane (parked car plus bike lane).

With our elbows akimbo, we’re about two and a half feet riding a bike, taking up about as much space as people in wheelchairs. Both protected bike lanes and sidewalks require a minimum of six feet of street right-of-way to accommodate people riding and rolling respectively.

Highways

Highways are a different case entirely when it comes to lane width.

You may have read the lane width on the Aurora Bridge was a factor in the recent collision fatality between a Duck amphibious vehicle and charter bus. It is up to the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) to determine causes, but Federal standards for highways recommend 12-foot lanes, in addition to shoulders wide enough for emergency parking and median barriers. Most lanes along I-5 are 12 feet wide. The Aurora Bridge lanes are 9.5 feet wide.

The relationship between lane width and safety is a question of geometry and psychology.

Cars range in width from a Car2Go Smart vehicle of about five feet, to a six-foot sedan, to a hefty seven plus-foot SUV. Mirrors add another six inches or so on each side of these vehicles. Buses, firetrucks, freight trucks, and amphibious vehicles almost all are 102 inches or eight and a half feet wide. Mirrors on these vehicles can add easily add another foot to each side, so mandating 12-foot bus and freight lanes on fast-moving highways is an entirely rational choice.

Lanes on highways need to be wide to accommodate wide vehicles moving quickly. Traffic on the Aurora Bridge is posted 40 MPH, while people driving average more than 10 miles an hour faster (p.19 here). The Aurora Bridge has had 144 crashes since 2005.

Narrow lanes are intended to be used slowly. Collisions at faster speeds result in much higher rates of injury and fatality.

Vision Zero

Vision Zero

Lane width is a factor in street safety and how we choose to engineer for Vision Zero.

I first visited Sweden in 1997, just when Vision Zero was getting started, and lived there for year from 2006-2007. The Swedish approach to Vision Zero was first to save lives on highways where many collisions end in serious injury or death. There was a great deal of public discourse on lane width, median barriers, and highway speeds. When Vision Zero launched in Sweden, there were seven traffic fatalities per 100,000 people. Despite more people driving, that number has dropped in Sweden to three per 100,000. In the US, our road fatality rate is 11.6 per 100,000.

Swedish Transportation safety strategist Matts-Åke Belin believes Vision Zero is achievable if experts agree to fund solutions to traffic safety.

I would say that the main problems that we had in the beginning were not really political, they were more on the expert side. The largest resistance we got to the idea about Vision Zero was from those political economists that have built their whole career on cost-benefit analysis. For them it is very difficult to buy into “zero.” Because in their economic models, you have costs and benefits, and although they might not say it explicitly, the idea is that there is an optimum number of fatalities. A price that you have to pay for transport.

The problem is the whole transport sector is quite influenced by the whole utilitarianist mindset. Now we’re bringing in the idea that it’s not acceptable to be killed or seriously injured when you’re transporting or walking or biking. It’s more a civil-rights thing that you bring into the policy. The other group that had trouble with Vision Zero was our friends, our expert friends. Because most of the people in the safety community had invested in the idea that safety work is about changing human behavior. Vision Zero says instead that people make mistakes, they have a certain tolerance for external violence, let’s create a system for the humans instead of trying to adjust the humans to the system.

As we move towards Vision Zero standards in Seattle, let’s examine the width of our streets as one of the contributing factors of our safety. As a call to action, please sign on to the principles of Seattle Neighbors for Vision Zero.

No one should die or suffer serious injury in traffic.

- Life is Most Important. The protection of human life and health must be the overriding goal of traffic planning and engineering, taking priority over vehicle speeds and other objectives.

- Every Person Matters. Everyone has the right to be safe on our streets, regardless of the way they choose to travel.

- People Make Mistakes. In order to prevent and reduce death and serious injury, traffic systems can and must be designed to account for the inevitability of human error.

- The Government is Responsible for Safe Streets. ALL elected officials and government staff need to collaborate and act now to achieve Vision Zero.

This is a cross-post that originally appeared on Seattle Neighborhood Greenways.