Article Note: This is the second installment of a two-part series on laneways. See Part 1 for background on efforts to enhance Melbourne’s laneway network including discussion of public realm initiatives.

Melbourne, Australia is internationally renowned for its vibrant laneways, which are dotted with street-side dining, unique stores and residences, creating an intriguing maze of connections for people to wander and explore. Given growing interest in enhancing Seattle’s alleys as public spaces, the revitalization of Melbourne’s laneways provides an interesting example. Like Seattle, Melbourne made a conscious effort to invest in laneways — from 1994 to 2004, accessible and active laneways in central Melbourne increased from just 8 percent to 92 percent.

Policy reform

In the mid-1980s, state liquor laws were relaxed, with the cost of obtaining a liquor license reduced significantly. Venues serving alcohol were no longer required to offer food. This minimized overheads including kitchen fit-outs and operational costs which had previously priced out smaller independent businesses. The changes enabled a greater variety of premises to serve alcohol such as small cafes, bars and restaurants. Unique spaces in laneways and on rooftops offered lower rents for entrepreneurs seeking to offer patrons a point of difference. Coupled with the permitting of street side dining, the changes had a transformative impact on the function of streets and lanes as spaces for socializing and dining. In the 1980s, there were just 2 outdoor cafes in central Melbourne, which has risen above 500 today. There are hundreds of little bars, and street-side cafes, hidden in Melbourne’s maze of laneways, creating a sense of intrigue and surprise.

Fostering activity

As part of the broader initiative to regenerate the central city, a mix of uses and variety of development were promoted to activate streets and lanes. The City introduced the ‘Postcode 3000’ initiative in the 1990s, which sought to transform the stagnant business district into a 24-hour city by encouraging people to live in the center. The City provided a range of financial incentives, technical guidance, promotion, policy change and street level support to encourage residential development. A focus of these efforts was re-purposing and re-designing the oversupply of offices and vacant heritage buildings and warehouses for residential use.

The number of residential units increased by 830% in a decade from approximately 1,000 in 1992 to almost 10,000 — today about 20,000 people live in the Central Business District. The growing residential community had a significant impact on the demand for retail, services, public space, and increased foot traffic in the inner city. Active street frontage policies contributed to a vertical mix of cafes or retail on street level, with apartments or offices above, improving the pedestrian experience. Many underutilized buildings were located on laneways contributing to their transformation.

Supporting art and culture

Public art projects were promoted to beautify the laneways. Today many of the laneways are world renowned for their street art, functioning as galleries as well as stages for performances. Art on the walls lining many laneways are treated as temporary, often layered over, providing an interesting and constantly changing experience for pedestrians and generating exposure for artists. The City has a unique policy regarding street art. Graffiti is not encouraged, however, the City provides permits for what is constituted as “legal” street art, where building owners have granted permission to the artist. Street art applied without permission of the building owner is removed.

In 2001, the City introduced a Laneway Commissions Program, in which artists are encouraged to develop a work for a specific lane. Each year several artists are selected to create temporary pieces. The laneways also provide spaces for music events. The largest examples include the St Jerome’s Laneway Festival, which transformed several laneways into stages for a one-day music event each summer from 2005 to 2009 and White Night, an all-night free music and arts event which takes over the city’s lanes and streets for people’s enjoyment, which commenced in 2013. Art and cultural features support the laneways as a significant tourist attraction.

Public life research

Melbourne is one of the only cities in the world with a formal and longitudinal research program for collecting data on public life and pedestrian activity. In 1994, the City engaged Danish architect and urban designer, Jan Gehl, to conduct a groundbreaking study of the quality of public space and human activity in the central city. The study ‘Places for People’ repeated in 2004 and 2014 (the latter is due to be released), provides a database documenting pedestrian counts and behavior in relationship to features of the urban environment, including the location and type of public spaces, street and laneway connections, building form, business types, residential buildings, and street furniture. The research assists the City to understand the condition of the public realm, the impact of changes to the built environment on pedestrian activity, and prioritize work programs. Gehl’s reports have documented the impact of laneway revitalization on the way people use the city as well as identifying opportunities for their ongoing improvement.

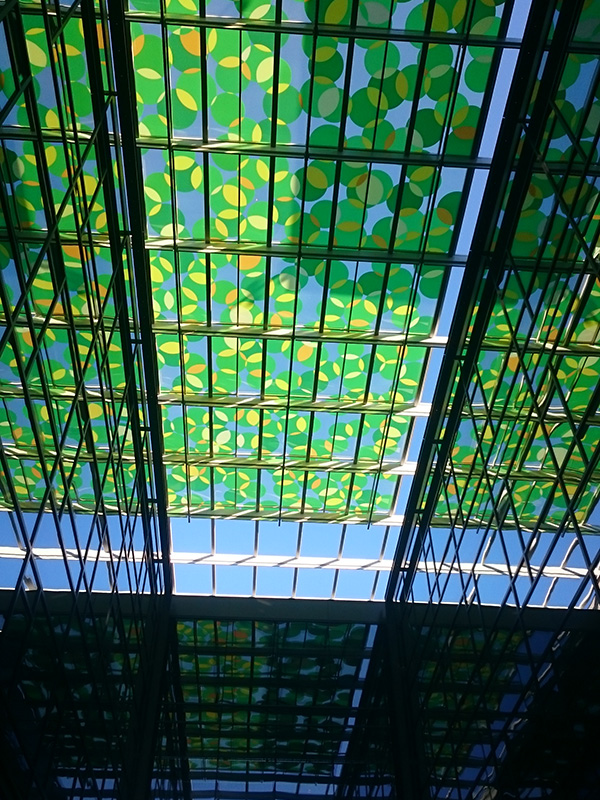

The Melbourne Planning Scheme provides guidance for development on laneways to support their diverse servicing, social, cultural, and economic functions. It classifies the quality of laneways, identifying many that would benefit from upgrades to enhance the pedestrian experience. New development on laneways is encouraged to support the human scale nature and pedestrian connections through articulated frontages, overlooking windows and balconies, and small tenancies integrated at ground level. Several recent developments in the city are separated by new passages, referencing Melbourne’s laneways. Developers recognize the laneways are a sought after location, offering appeal to businesses, and in many cases have integrated new public laneways and arcades through developments. Examples include major retail stores QV, Melbourne Central and GPO; and public buildings at Southern Cross Tower, Southern Cross Station, Federation Square and the base of the City of Melbourne’s green headquarters, CH2.

With an estimated 844,000 people (the equivalent to one-fifth of the population of metropolitan Melbourne) visiting the central city everyday, laneways are an important public space asset. The revitalization of laneways has helped to repair missing links in the pedestrian network, providing unique routes to support increased walking activity. In Seattle, this revitalization has already begun, and with more residents choosing to live downtown, appreciation for the alleys as public spaces will grow. As in Melbourne, incremental and cumulative policy, urban design and programming efforts will be the key to making alley revitalization on a broader scale successful in Seattle.

Sarah is an urban planner and artist from Melbourne Australia, currently living in Seattle. She has contributed to diverse long-term projects addressing housing, transportation, community facilities, heritage and public spaces with extensive consultation with communities and other stakeholders. Her articles for The Urbanist focus on her passion for the design of sustainable, inviting and inclusive places, drawing on her research and experiences around the world.