Last week the Seattle City Council reluctantly approved forwarding the Alaskan Way Viaduct preservation effort to the August 2016 ballot. The group known as “Park My Viaduct” will seek voter approval for Initiative 123, which would create a public development authority (PDA) to build and operate a mile-long elevated park on the Alaskan Way waterfront. I was one of the first local writers to cover the campaign in depth. Now that it’s headed to the voters new details are available, but I will reiterate my position the idea is against the public’s best interests.

Last week the Seattle City Council reluctantly approved forwarding the Alaskan Way Viaduct preservation effort to the August 2016 ballot. The group known as “Park My Viaduct” will seek voter approval for Initiative 123, which would create a public development authority (PDA) to build and operate a mile-long elevated park on the Alaskan Way waterfront. I was one of the first local writers to cover the campaign in depth. Now that it’s headed to the voters new details are available, but I will reiterate my position the idea is against the public’s best interests.

Background

The Waterfront Seattle project started with a 2001 earthquake that damaged the Alaskan Way Viaduct, a concrete, double-deck bridge that has carried six lanes of Highway 99 traffic on Seattle’s downtown waterfront since the 1950s. The downtown seawall, made of wood, was also damaged. There was great debate between governments and civic organizations over what to do about this, and eventually Governor Christine Gregoire opted for a $2 billion deep bore tunnel to replace the viaduct. The choice didn’t satisfy advocates for a surface street and transit improvement option, nor will it particularly help downtown drivers: the tunnel only has four lanes, won’t have downtown exits, and won’t serve any purpose for transit trips. And now costs will likely soar since the machine digging the tunnel broke down nearly two years ago.

But the tunnel option did create the opportunity for Seattle to rebuild its public waterfront. The seawall, the linchpin for everything, is currently being rebuilt as a modern concrete structure. Once funding is secured, the rest of the plan is to rebuild Alaskan Way as a wide multi-modal street with a large waterfront promenade, a two-way bike path, and ferry queue lanes. Streets leading to the waterfront will be upgraded with better pedestrian facilities, and access will be improved with a wider Marion Street pedestrian bridge and a combination bridge and elevator at Union Street. Some piers will be repurposed as public parks. And the Seattle Aquarium will undergo a large expansion, including an exhibit underneath a terraced lid leading from Pike Place Market to Alaskan Way. The schedule has construction starting around 2019, but that is tentative based on the viaduct coming down.

Jumping on the delay of the viaduct’s demolition is Kate Martin, a resident of Seattle’s Greenwood neighborhood. With a degree in landscape architecture, she describes herself as a designer of small home and business projects. She ran for Seattle mayor in 2013 on a campaign platform that included a vision of preserving the viaduct for use as a park. Losing with less than 2 percent of the vote, the idea clearly didn’t resonate with the public. Despite this, Martin started the Park My Viaduct campaign soon after the tunneling project was stalled, a month later in December 2013.

Martin told me she is deeply disappointed with the “status quo” waterfront plan. She rattled off a number of issues: the planned promenade will be spoiled by service driveways, ferry loading, and truck traffic; pier buildings block waterfront views and visitors won’t be able to touch the water; the Overlook Walk lid over a Seattle Aquarium expansion won’t generate business for the expanded Pike Place Market; and the rerouted Elliot Avenue, intended to enable a bypass of railroad traffic in Belltown, will negatively impact condominium owners on Alaskan Way. Martin also said demolishing the viaduct will squander a public view asset worth $200 million, based on current downtown land values, but that misses the fact that the viaduct was built for a transportation purpose and can’t be compared to private land values that are tied to residential and commercial markets.

Engineering study

I-123 needed to verify their idea, so they paid $150,000 for an engineering and finance study (16 MB PDF) by international firm BuroHappold Engineering. The study presents two basic alternatives: retrofit the viaduct or rebuild it.

The study modeled retrofit options that preserved both roadway decks or removed the lower deck, but didn’t consider any options where only the top deck was removed. It also did not complete a full seismic evaluation. It states, “Since the degree of damage caused by the past earthquake events is not known, there is a risk that the existing structure is beyond repair or strengthening associated with these options. Extensive investigation will be required.”

With both alternatives, a 400-foot section of the viaduct directly adjacent to Pike Place Market would be preserved. That section has “…six architecturally interesting outriggers where the beams supporting the upper deck stretch out over the southbound lanes just north of where the structure becomes a double-deck highway”, the study says.

The results paint a dreary picture for Park My Viaduct’s original vision. It finds high risk in preserving the curving part of the viaduct at Washington Street and any section south of there; without a modern seawall in that area, the structure will be susceptible to the land falling out from under it in an earthquake. Elsewhere, the viaduct’s foundations would need to be greatly expanded and the beams and columns would require protection with steel jackets and new layers of reinforced concrete. The study then assumes that in Alternative 1 the viaduct is only retrofitted between Pine Street and Madison Street, and rebuilt as an elevated promenade south of Madison Street. The cost comes to $262 million.

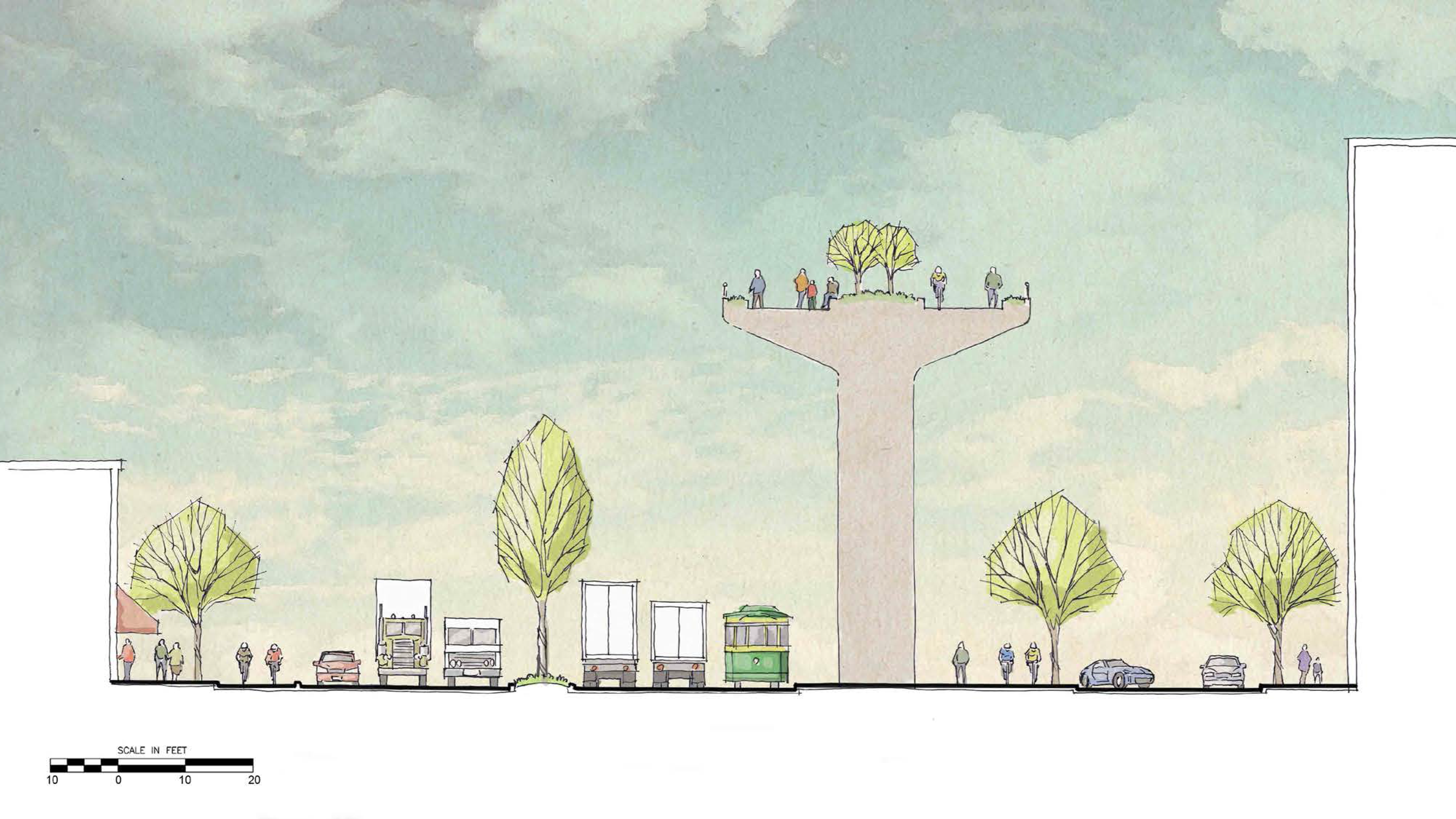

In Alternative 2, more of the structure is demolished and rebuilt as a “garden bridge” between the preserved 400-foot section at Pike Street and the football stadium in Pioneer Square. The garden bridge would contain landscaping and a pedestrian way, but it would have little practical transportation purpose. Minutes from an October 2014 meeting included in the report say the park is “…not going to be a commuter route. It will be for recreational use, be a trail and [slow-moving bicyclists] might be segregated by lanes/patterns.” This alternative costs less, $165 million, and is what the campaign is opting to pursue.

The study determined 1,000-foot ramps are needed to accommodate a comfortable 1:20 gradient from the street level. This is even longer than the 770 feet I previously calculated with a maximum 1:12 gradient. According the I-123 website stairs and elevators are also proposed every two blocks. The feasibility study noted urban outdoor elevators are difficult to maintain. Also proposed are a new bridge connecting to Union Street and three links to Pike Place Market. The existing Seneca Street and Columbia Street ramps would be demolished as already planned.

Martin said I-123’s plan would create a much more “humane” environment, with the garden bridge providing shelter for a walkway on the east side of Alaskan Way, on-street parking, and food truck spaces. She believes the current design leaves a wide promenade too exposed to the elements and would be relatively desolate during the non-summer months. But a narrow, 50-foot tall structure with wide spacing between columns would hardly provide adequate weather protection. Martin also anticipates bringing back the waterfront streetcar, which was closed when its maintenance shed was demolished to make way for Olympic Sculpture Park. That idea has actually been studied (PDF), but Waterfront Seattle is likely to lean towards a bus option.

Questionable intent

Initiative 123 would create a Downtown Waterfront Preservation and Development Authority (DWPDA) to manage the project. A PDA is a public corporation that can use both public and private funds for construction, operations, and maintenance of special projects. It is the same type of state-authorized entity that manages Pike Place Market and Capitol Hill Housing. Six others operate within Seattle. (I earlier speculated that the campaign would seek a citywide levy or a local improvement district for funding and ownership would be assumed by the city.)

Under the city’s initiative process, to qualify for passage I-123 was required to get 20,638 voter signatures (10 percent of the voter turnout in the last mayoral election). Coincidentally, I encountered one such campaigner at Green Lake Park, the same park that Martin compares her vision to. Friends of Waterfront Seattle (Friends) took issue with the fact that the petitions appropriated the “waterfront for all” phrase that has been used by Waterfront Seattle for years. In June, the Friends board of directors sent a letter to Martin listing their concerns with I-123.

The letter (PDF) explains that Seattle has held “Over 400 public meetings, reaching over 15,000 people, generating more than 9,000 comments that were considered in creating the design”, and also met with business groups, neighborhood organizations, and minority communities. In response, Martin told me that she has heard from “many, many” people who are disappointed with the official plan. I told her Friends’ letter includes polling data that shows 85 percent of Seattle voters approve of Waterfront Seattle, and that “…Support is extremely strong in every city council district and voters support the project without any persuasion messaging.” Martin had no comment except to say, “we’ll let the voters decide”.

Friends’ letter says I-123 is designed to benefit private real estate interests through an unelected board. The initiative’s language states that the project will provide “…anchor real estate developments at the north and south ends of the park to sustain the project…” No other funding sources are identified in the initiative text, but the I-123 website says the project “…reallocates existing funding sources from the unimproved plan…”, possibly jeopardizing Waterfront Seattle. And I-123 establishes the DWPDA’s board members immediately upon I-123’s passage, three of whom have contributed to the campaign: Kate Martin, Teri Hein, Richard Warner, Susan Bean, Don Harper and Irene Wall. When a similar PDA was proposed to revive monorail planning last year, an effort that Friends compares I-123 to, Citizen Petition 1 listed board members who were actually unaware or even opposed to the monorail campaign.

The letter also calls out Article V, Section 24, which states: “…real or other property held by any public agency within the city limits of Seattle which is unused, under-used or surplus, be made available to DWPDA, and such property shall be made available to DWPDA without charge if there is no legal prohibition”. This would allow the DWPDA to seize vacant or surplus land that Seattle may consider for parks, utilities, or affordable housing.

This summer I-123 scraped by with about 1,000 more signatures than it needed to be considered by the Seattle City Council. The Council chose to reject it this month, requiring the voters to have a say in the next election cycle. The Stranger reports that the campaign requested placement on the November 2016 ballot, but the Council declined. I-123 will appear at the August 2, 2016 primary election when voter turnout is lower. The Council noted their frustration in Resolution 31607: “Initiative Measure 123 is inconsistent with the Strategic Plan, Central Waterfront Concept Design and Framework Plan, and the Funding Plan for the Waterfront redevelopment and improvements and undermines the vision for Waterfront Seattle”.

Growing opposition

Martin Selig, a Seattle developer and the campaign’s primary financial backer, reportedly contributed $300,000 for the feasibility study, lawyers, and signature gathering. Kate Martin told me she’s never actually met him. But Selig pulled his support when Alternative 2 was adopted, saying that the plan had changed too much from the original vision. Martin has poured at least $50,000 of her own money into the campaign, according to Ethics and Elections Commission records.

The campaign has frequently compared itself to the High Line in New York City, an elevated railroad spur that was brought out of abandonment and converted to an attractive pedestrian park. It was designed in part by James Corner, a renowned landscape architect who has worked to breath life back into old infrastructure and decaying urban sites. However, the High Line is much narrower, only 25 to 30 feet off the ground, and hugs adjacent buildings or even runs through them. The Alaskan Way Viaduct is double in size, being typically 58 feet tall and 47 feet wide, and opposes neighboring buildings.

In a bit of civic poetry, Corner is also working on Waterfront Seattle. And he is opposed to I-123, calling it a “dumb idea”. He disagrees with the High Line comparison, and told the Puget Sound Business Journal, “The day [the viaduct] comes down and people can see the sky and the quietness, this issue will be completely moot…Nobody will want to build another floating deck that bisects the sky and casts a shadow and is out of scale.” Martin agreed that Corner’s opinion is ironic, and added that his role with the High Line is overstated.

Heidi Hughes, Executive Director of Friends of Waterfront Seattle, told me, “Getting rid of the barrier between the city and Elliott Bay has been a goal of the public for decades. Significant environmental benefits are part of the current design…[that] would go away with an elevated structure.” When asked how her organization will deal with I-123, she said, “Friends will want to be sure that voters understand what this proposal would truly allow and all of the negative consequences of its passage”. She said distractions like I-123 are not uncommon on large projects like this, and ultimately Friends “will deal with it and roll on”.

If the ballot measure passes it’s unclear if the DWPDA would actually move forward or if the project could be built. Hughes of Friends said, “legal action is a possibility.” Because the project is proposed in public right-of-way Seattle could possibly stop it though denying construction permits or finding that it will require a new environmental impact statement subject to exhaustive agency review and public comment. Seattle’s Office of the Waterfront was not able to be reached for comment on these questions.

With engineering and financial setbacks, the question now is whether Initiative 123 can gain any momentum against the political tide. It has a year to do so, but it has lost its main donor and it’s clear the voters, the City Council, and the waterfront planners prefer the established plan that they’ve put years into crafting. I-123’s urban design qualities are largely negative and insensitive, it fails to acknowledge the years of planning that has already gone into Seattle’s new waterfront, and its governance scheme is suspect. Seattle residents will consider these serious drawbacks next year when I-123 comes to a vote.

This is a cross-post from The Northwest Urbanist.

Editor’s Note: This article has been updated as of 5:35pm, September 8, 2015.

Scott Bonjukian has degrees in architecture and planning, and his many interests include neighborhood design, public space and streets, transit systems, pedestrian and bicycle planning, local politics, and natural resource protection. He cross-posts from The Northwest Urbanist and leads the Seattle Lid I-5 effort. He served on The Urbanist board from 2015 to 2018.