Kitsap Transit plans to begin high speed foot ferry service between western Puget Sound and Seattle within the next few years. Trips between Bremerton and Seattle would be 25 to 30 minutes faster than the current car ferry run, and the agency’s business plan outlines ideas for similar service to the unincorporated communities of Kingston and Southworth. If the project proves sustainable, unlike many previous efforts, it will reinforce economic connections across Puget Sound and provide a boost to small communities on the peninsula.

Puget Sound ferries date back over 100 years, beginning with a ragtag collection of private services known as the Mosquito Fleet. Over time the companies merged, and by the 1930s the Black Ball Line was the sole operator. It introduced car-carrying ferries around the same time, purchased from San Francisco companies as the Bay Area began building bridges. After WWII, Black Ball Line cut service and raised prices in response to lowering demand. Squabbles between the company, the public, and the state eventually led to Washington state purchasing the company for $4.9 million in 1951.

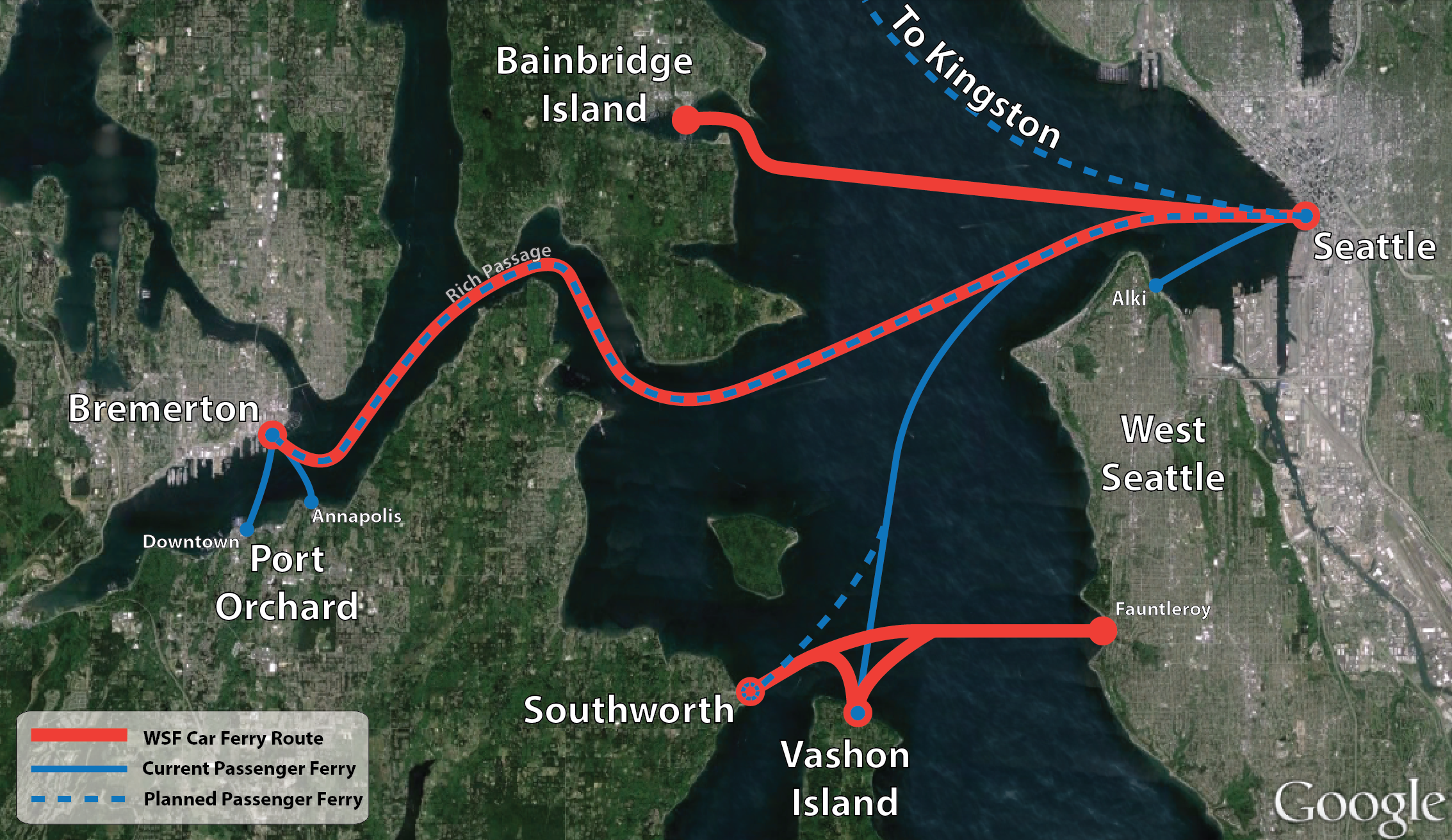

Today Washington State Ferries (WSF) is the largest ferry system in the United States, carrying some 22 million passengers per year on 10 routes and 22 vessels. There are numerous other routes, public and private, serving the Puget Sound. King County runs a water taxi between downtown Seattle and West Seattle hourly and to Vashon Island during commute hours. Clipper Navigation runs passengers from Seattle to the San Jan Islands and Victoria, Canada. Black Ball Ferry Line operates a car ferry between Port Angeles and Victoria. And Kitsap Transit runs half-hourly and quarter-hourly foot ferry routes between Bremerton and Port Orchard. Kitsap Transit, a separate government entity from Kitsap County, is behind a renewed effort for high speed, passenger only service between the Kitsap Peninsula and downtown Seattle.

For decades WSF has run a Bremerton-Seattle route that takes 60 minutes, the longest in the system. Bremerton is the largest city in Kitsap County and is home to a major Navy shipyard, so there have been several previous attempts to provide faster service between the two cities. Notably, in 1998 WSF began high speed service with two 350-passenger ferries built in Anacortes, the MV Chinook and MV Snohomish. The 30 minute crossing did well, carrying over 800,000 annual passengers. But only a year later, waterfront property owners sued WSF in response environmental damage caused by powerful wakes along Rich Passage, a narrow strait between the mainland peninsula and Bainbridge Island. A court-ordered study published in 2001 recommended much of the trip be reduced from 34 knots to 16 knots, ending the service’s speed advantage and leading to declining ridership. After the plaintiffs received settlement, the state legislature pulled funding and WSF ended the service in 2003. Except for infrequent backup service on other routes, the two ferries were mothballed until San Francisco’s transit district purchased them in 2008.

As another private stint in the mid-2000s failed, WSF obtained federal grant money in 2004 to further study the issue. The next year Kitsap Transit took over the Passenger Only Fast Ferry Study. A team of researchers looked at the unique geology and marine environment of Rich Passage, and built computer models of different wake patterns. Property owners and residents from Bainbridge, Port Orchard, and the rest of the county were actively involved. Much the study’s $8 million federal funding was earmarked by Congressman Norm Dicks, who has since stepped down.

In 2009, the study concluded that a catamaran with a foil could reduce wake enough at high speeds to prevent shoreline damage. Kitsap Transit signed a deal with All American Marine of Bellingham to custom build a $5.9 million ferry, the 118-passenger Rich Passage 1. Instead of propellers it uses water jets, and the weight is kept down with an aluminum and composite structure. The foil is hung between the two hulls and shaped like an airplane wing to provide lift at high speed, allowing the vessel to ride higher in the water and face less resistance.

The vessel was first tested in Bellingham (during which the foil broke off), and later in Kitsap’s waters, where it was confirmed that 37 knots is the optimum speed for wake reduction in Rich Passage and 32 knots is best for fuel efficiency elsewhere. In summer 2012 the ferry operated for four months as a successful demonstration service. It’s had a few mishaps since then. On the way to storage in Port Townsend in 2013 it ran aground with minor damage, and while in storage it caught fire and had to be repaired. A few months ago it was moved back to Bremerton in anticipation of promotional service for Seahawks football games, but Kitsap Transit couldn’t secure funding in time.

Over the past year the agency has developed a draft business plan supported by two public surveys and an economic analysis. The agency found riders would be willing to pay up to a $3 premium over the comparable trip cost, but some 60 percent of operating funds will need to be subsidized. If county voters approved a 0.2 percent sales tax increase, which was found to acceptable by a majority of survey respondents, Bremerton-Seattle service would start within six months. In the following years the agency would purchase three more ferries to directly connect Kingston and Southworth with downtown Seattle. Kitsap Transit would likely partner with King County for operating and maintaining the vessels.

John Clauson, executive director of Kitsap Transit, said at a community meeting on Saturday that it’s unlikely the agency’s board of commissioners will bring a sales tax increase or a car tab fee to an election this year. The Bremerton route has the highest demand, so it’s not clear that the entire county would be willing to pay for it. The agency may ask for legislative authority to create a “ferry district” that would charge a property tax or parking tax in a smaller area around the terminals. This would be a subset of the agency’s countywide 1 percent sales tax authority, which is nearly maxed out at 0.8 percent.

As for capitol funding, starting up two additional routes will require $45 million for acquiring ferries and upgrading facilities. This could come from bond financing or grants, like the federal New Starts program that competitively funds startup transit projects. The Bremerton dock is ready to go, and was recently upgraded with refueling capabilities, accessibility ramps, and hand rails. Kingston has a passenger dock that requires minor upgrades, and Southworth has no such infrastructure. WSF is already planning reconstruction of Seattle’s Colman Dock.

A sample schedule envisions six trips per weekday to start with. Bremerton, for instance, could have morning departures at 5:45, 6:55, and 8:05, and the return trips from Seattle would be at 3:25, 4:35, and 5:45. A survey found riders would most prefer additional service on weekday evenings. The plan conservatively estimates Bremerton-Seattle ridership of 218,000 per year with one vessel and 430,000 per year with two vessels, in which case there would be twelve trips per weekday. Southworth and Kingston, respectively, may attract 178,000 and 147,000 riders per year.

Whatever the service ultimately looks like, it will have positive impacts for all of Kitsap County. The area offers a high quality of life and cheaper cost of living, and connecting it to the region’s major job center with rapid transit could encourage more people to move to the peninsula. Almost $10 million in property value increases will spur an economic boon for small communities like Kingston and Port Orchard, and could facilitate the revitalization of town centers and mixed use development as ferry commuters move in.

For more information, visit Kitsap Transit’s information page on the project.

This is a cross-post from The Northwest Urbanist.

Scott Bonjukian has degrees in architecture and planning, and his many interests include neighborhood design, public space and streets, transit systems, pedestrian and bicycle planning, local politics, and natural resource protection. He cross-posts from The Northwest Urbanist and leads the Seattle Lid I-5 effort. He served on The Urbanist board from 2015 to 2018.