Human settlements are built on the bedrock of food access. Without adequate sustenance, urban environments cannot flourish. People will travel long distances to ensure that they are adequately fed, and so it’s no surprise that rural and suburban dwellers will often traverse many miles to the nearest food source. But urbanities would appear to have an especially unique advantage of food access on their side. After all, dense urban environments naturally mean an increased density of food sources and less distance between them. But access to food is not entirely equal in Seattle, and data from Walk Score shows it.

Last year, Walk Score set out to determine the access and diversity of grocery stores in major cities across the country using their walking algorithm. They wanted to see where food deserts and food havens were. Walk Score identified grocery stores by using a variety of data sources (in-house, Localeze, and Google). They also defined what their criteria would be for identifying individual grocery stores. They decided to limit their search for grocery stores by excluding convenience stores and requiring that a food store sell produce.

On the face of it, that seems like fairly reasonable criteria. Convenience stores may not offer a diversity of products to truly sustain the needs for an affordable and varied diet. Yet, a grocery store that sells produce is likely to have a wider diversity of goods that range in quality. With that in mind, let’s look at what Walk Score found for Seattle food access and choice.

Choice and Access maps

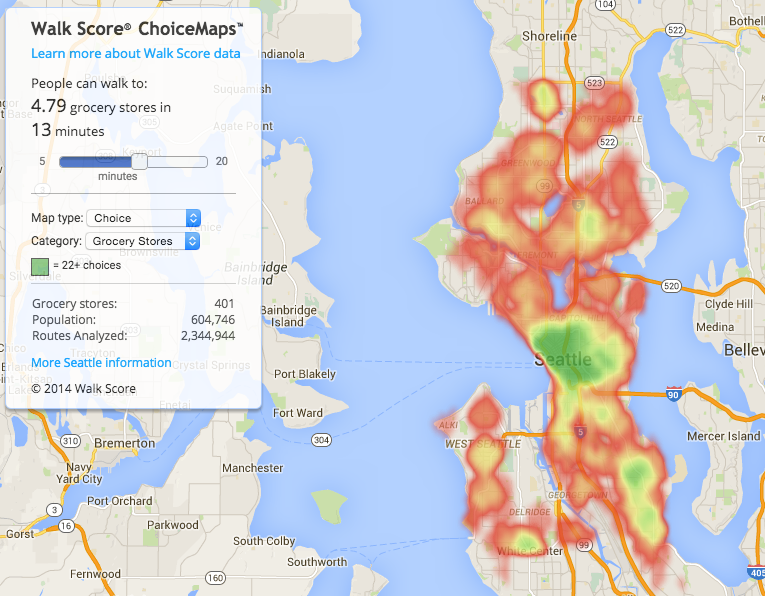

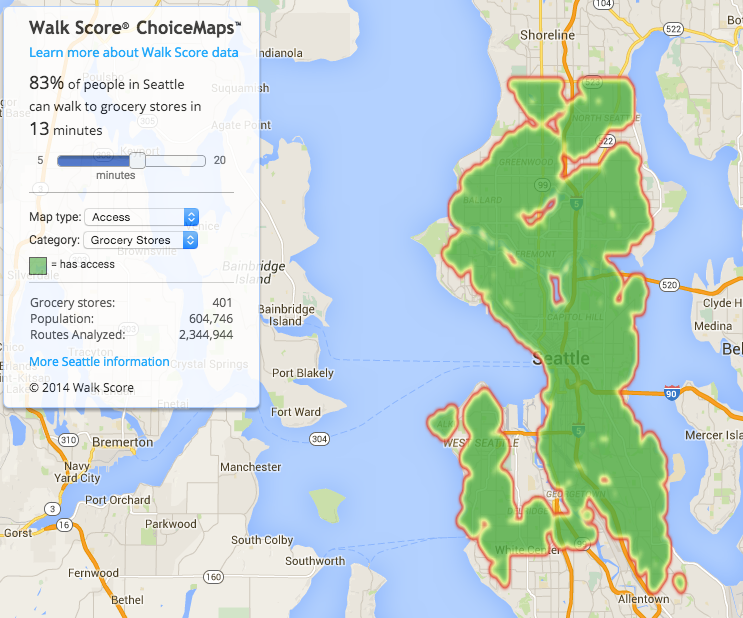

Walk Score’s data looks at grocery stores in two differing ways: choice and access. The first of these, grocery store choice is shown as a heatmap. The greener the color, the more choice a particular area has for grocery stores while extent of the red-to-green color shows the related walkshed being analyzed. Meanwhile, the grocery store access map series depicted solely as green to the areas with access to at least one grocery store.

Walk Score’s most recent data would suggest that there are 401 grocery stores within the city limits. When it comes to access, Seattle seems to score pretty well in the 10-minute and 15-minute walkshed maps below, with 70% and 87% of residents having access respectively. When it comes to choice, the 15-minute walkshed map provides more than twice as many grocery store choices for the average resident than the 10-minute walkshed map. With only 2.78 grocery stores within a 10-minute walk, the diversity of choice for the average resident seems modest.

5-minute walkshed

The 5-minute walkshed maps seem to be a mixed bag. On the one hand, Downtown Seattle has relatively good access and choice to grocery stores. Belltown is the shining star here in both regards. But, only 31% of Seattle residents actually have access to a grocery store within a 5-minute walk of their homes. Even worse, most residents end up with a very low ratio for grocery store choice, which stands at 0.64 grocery stores within a 5-minute walkshed.

10-minute walkshed

Within a 10-minute walkshed, things get considerably better for Seattle. Urban centers and urban villages appear to have the best variety of grocery stores. Accessibility to grocery stores is more than twice the 5-minute walkshed with 70% of residents being able to walk to a grocery store in 10 minutes. Areas of the city that still fall outside of the 10-minute walkshed tend to be located at the fringes of the city. Although, some significant areas toward the interior of the city stand out like High Point, Ravenna, and Delridge. (Keep in mind that many areas near the Seattle city limits like White Center and Skyway are under other jurisdictions and are therefore excluded from the Walk Score analysis.)

15-minute walkshed

At the 15-minute walkshed, over 87% of all Seattle residents have access to a grocery store. This is a pretty healthy number, and 13% more than the 10-minute walkshed. However, the increase in access is not as dramatic as seen between the 5-minute and 10-minute walksheds. Again, areas toward the fringes (e.g., Broadview, Magnolia, and Sand Point) of Seattle remain outside of the 15-minute walkshed. If you put Seattle in the context of geography and development patterns, then this makes a lot of sense:

- For starters, the fringes tend to be lightly developed and often have significant vertical grades or other geographic constraints that make access to grocery stores less feasible for residents on foot;

- Businesses that typically demand a high volume of patronage (e.g., supermarkets) are unlikely to relegate themselves to location near the fringes largely because the customer base is likely to be low; and

- Most grocery stores are located within commercial zones that permit them. Those types of zones are not usually located along the fringes.

But Delridge remains as a glaring food desert within the 15-minute walkshed. No grocery store of any kind is accessible to those on foot. On the flipside, the Rainier Valley boasts phenomenal access to grocery stores–and grocery store choice. In some ways, this comes as a surprise given that low-income and communities of color are usually the primary victims of food deserts, and this map series appears to suggest otherwise.

The other big detail in the 15-minute walkshed is grocery store choice. This number more than doubles over the 10-minute walkshed. The average Seattle resident willing to walk 15 minutes is likely to find 6.29 grocery stores.

Analysis, Caveats, and Concluding Points

Walk Score sets a 5-minute walkshed as the minimum threshold for analysis. It’s a nice, small number–and probably would be satisfying for most people. But as we can see from the 5-minute walkshed map, Seattle doesn’t deliver so well on access to grocery stores within that walkshed timeframe, and perhaps even worse in the diversity of choice.

If you consider the average shopper, there is a happy medium in what they’re willing to walk. A 10-minute roundtrip walk is a breeze; that’s 5 minutes out and 5 minutes back. Most shoppers are almost certainly willing to take up a longer walk than this for their daily food needs. If I had to pick a fixed roundtrip time as a maximum, it’s probably more than 20 minutes, but less than 30. Beyond this roundtrip timeframe, people will likely pursue other options that are faster like biking, busing, or driving.

Using that broad 20-to-30-minute roundtrip walk threshold, we can reasonably exclude the 15-minute walksheds as a standard for access and choice to grocery stores. It’s not clear what the magic number is, but let’s assume it’s 26 minutes for a 13-minute walkshed. The resulting data points from this aren’t markedly different from the 15-minute walkshed. In this instance, 83% of Seattle residents end up within a short of grocery store and have a choice of 4.79 grocery stores on average.

Despite all of this, what we don’t know is the actual diversity or quality of grocery stores that Walk Score is counting in Seattle. There’s no way to distill down the details about the 401 stores that their database is measuring. We can assume, at worst, that their definition covers the limited offerings sold in many bodegas and corner stores, and, at best, the breadth of goods sold at Uwajimaya and Fred Meyer.

It’s entirely possible that many areas that appear to have access and/or abundant choice, actually have poor offerings of food in terms of the quality, cost, and variety. At the same time, not all chain grocers–which are not identified by Walk Score–are even created equal themselves. Safeway, a large grocer in the area, runs on a spectrum for store formats for size and diversity of food choices. Meanwhile, Walk Score chooses to exclude convenience stores and stores that don’t sell produce (e.g., 7-Eleven and Walgreens) in spite of the fact that they may provide important local access to basic needs of consumers. Ultimately, it’s difficult to draw absolute conclusions on what these maps mean for quality, walkable access to food sources.

Regardless of these issues, it is clear that most people in Seattle still live or work within a very reasonable distance of a grocery store–even if we toss out the 15-minute walkshed maps. But in areas where choice and access are low, they present compelling cases for local growth. Because, as we know, growth and added density eventually beget important urban benefits like neighborhood food sources. Many neighborhoods would love to have the problem that Capitol Hill (land of a million QFCs) is faced with–residents there get to debate whether or not another boutique grocery store could be great addition to neighborhood’s beloved Broadway corridor.

Stephen is a professional urban planner in Puget Sound with a passion for sustainable, livable, and diverse cities. He is especially interested in how policies, regulations, and programs can promote positive outcomes for communities. With stints in great cities like Bellingham and Cork, Stephen currently lives in Seattle. He primarily covers land use and transportation issues and has been with The Urbanist since 2014.