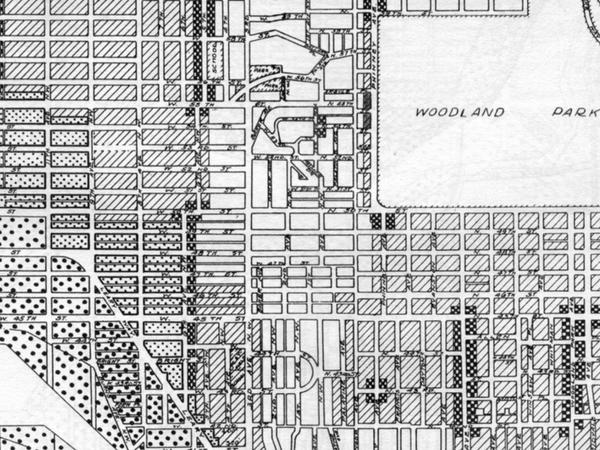

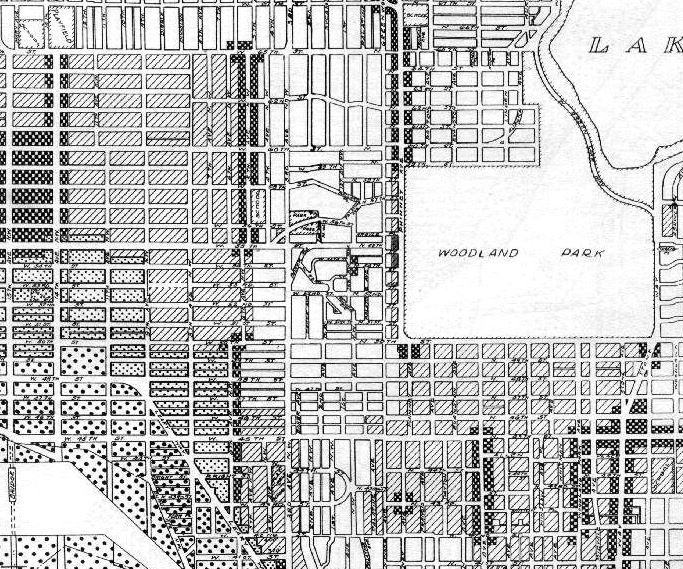

The Seattle City Clerk’s website keeps an expansive online repository of historic zoning maps. I seem to always find myself perusing the 1923 maps in particular. The 1923 zoning ordinance was essentially a snapshot of how Seattle had been developed up to that point. There seems to have been little, if any, planning at the time. And despite this document being nearly one hundred years old (and rather poorly thought out for a city ), it’s actually more progressive in some ways than present zoning. Or at least, it was less restrictive than now.

My wife and I have lived in Fremont since moving here, and now that we have kids, we spend a lot of time at our local parks. We’re aware of which roads are quite inhospitable to cyclists and pedestrians, and tend to avoid walking on arterials because, well, mostly because we don’t live in the Freiburg fussgaengerzone anymore. Drivers speed excessively on the roads around us.

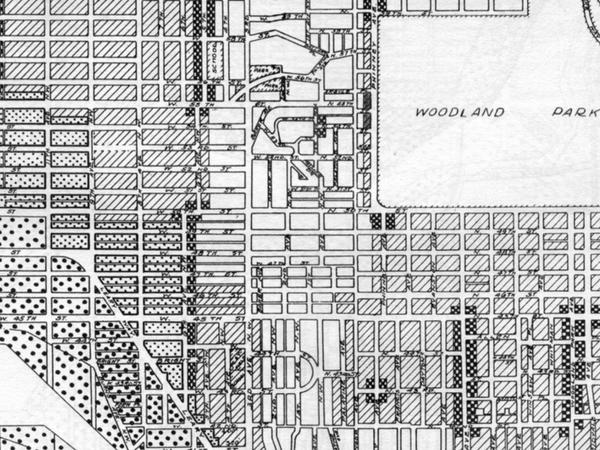

So it was with delight, and also a lot of disgust, in looking over the ‘Frelard’ map that I noticed that this whole area once had a beautiful, continuous grid. Sure, the topography on some streets isn’t the easiest to hike with kids, and there’s criminally little commercial, but holy cow, over the course of time, the City laid down quite a few scars.

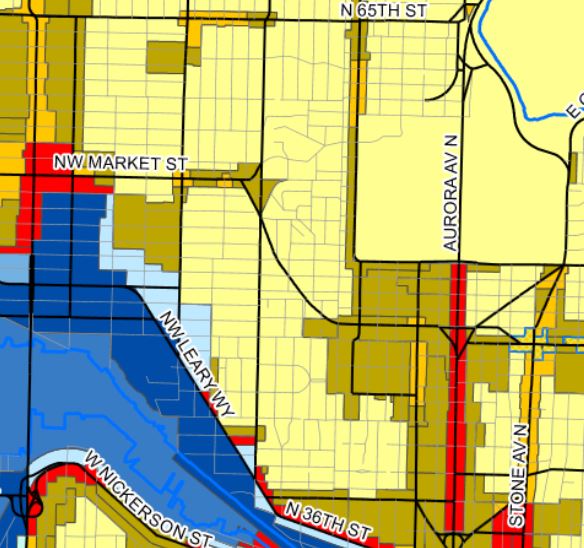

The first one that stands out is the stretch of Market that angles down from NW Market Street at 4th Ave NW to N 46th St and Greenwood Ave N (map). The speed limit on this stretch of road might as well be 50mph. This ‘improvement’ divided through at least 10 blocks, and cut off several more from even accessing it, either due to slope conflicts or to prevent accidents. Some of these cut off sections would have made great woonerven (they’re actually in residential districts).

Green Lake Way stands out as essentially a mirror Market Street on the east side of Aurora Ave. It slices through the grid from the northbound offramp at N. Allen Place to Green Lake Way & N 50th Street (map). It’s pretty much the same effect–8 blocks were hacked up and several more restricted access. An inhospitable speedway dividing the southern half of the road from the north. Good luck trying to cross, I’ve seen several accidents and near-fatalities with pedestrians attempting to ‘frogger‘ across. Some of the lots here could actually have set the stage for interesting buildings, but the zoning has overwhelmingly prevented that.

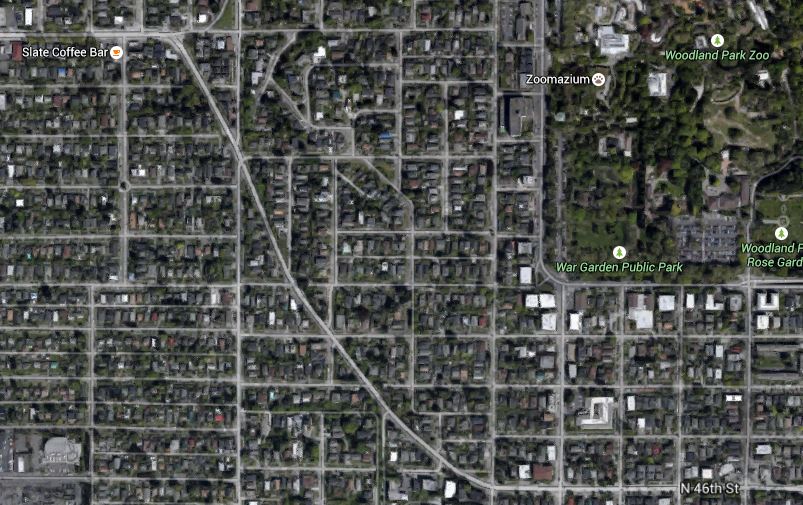

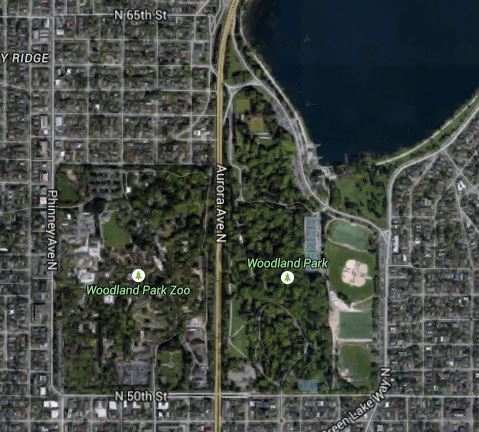

The third scar in the North Fremont area that really stands out, and also has always irked me, was the bisection of the Olmsted-planned Woodland Park into two separate parcels. Sure, there are some (horrendous) overpasses that link them. Hurrah! The total area of the park is approximately 250 acres per the GIS–if you include the Aurora Ave N right-of-way, parts of the park that stretch north, and the off-ramp at Green Lake. Unfortunately, the 1923 use map for this section was zoned ‘First Residence District’. Given the size of a contiguous Woodland Park, roughly a third of Central Park, this could have been something really amazing had the park been preserved. Painful, no?

The last scar that stands out to me is likely the most heinous. However, at this point, it’s also the easiest to rectify (ahem, Seattle City Council). At the time of the 1923 zoning ordinance, the overwhelmingly majority of blocks between 3rd Ave NW and 14th Ave NW, from N 65th St clear on down to Leary Way, was zoned for the following uses: multifamily, business, or commercial. Those diagonal-hatched blocks were zoned for ‘Second Residence District’–also knows as multifamily. Anyone want to take a guess what the present zoning of nearly every one of those blocks is today?

Mike is the founder of Larch Lab, an architecture and urbanism think and do tank focusing on prefabricated, decarbonized, climate-adaptive, low-energy urban buildings; sustainable mobility; livable ecodistricts. He is also a dad, writer, and researcher with a passion for passivhaus buildings, baugruppen, social housing, livable cities, and car-free streets. After living in Freiburg, Mike spent 15 years raising his family - nearly car-free, in Fremont. After a brief sojourn to study mass timber buildings in Bayern, he has returned to jumpstart a baugruppe movement and help build a more sustainable, equitable, and livable Seattle. Ohne autos.