A month ago, I made the case for why urbanists must support linkage fees. In response, Dan Bertolet at Smart Growth Seattle argued that linkage fees will impede housing production. Bertolet starts by summarizing how planners estimate redevelopable capacity, a critical concept in planning. He then firmly declares that a decrease in land values without a change in improvement values will decrease the supply of land, and consequently the supply of housing.

Bertolet, an urban planner at VIA Architecture, brings a valuable perspective to the debate. He has a lot of planning experience, and a long history advocating for a more sustainable city.

Both Bertolet and Roger Valdez (the director of Smart Growth Seattle) seem to agree with me that the cost of linkage fees would be passed to landowners. But we clearly disagree about whether reduced land values affect the supply of land. Cutting to the heart of the matter, Bertolet is making a claim about the economic nature of land. Do high prices mean there’s more land for sale? Do low prices mean there’s less?

Land Is Uniquely Inelastic

As I previously argued, the supply of land is, for all practical purposes, inelastic; that is, land prices have no impact on supply. Here’s how Wikipedia describes land economics:

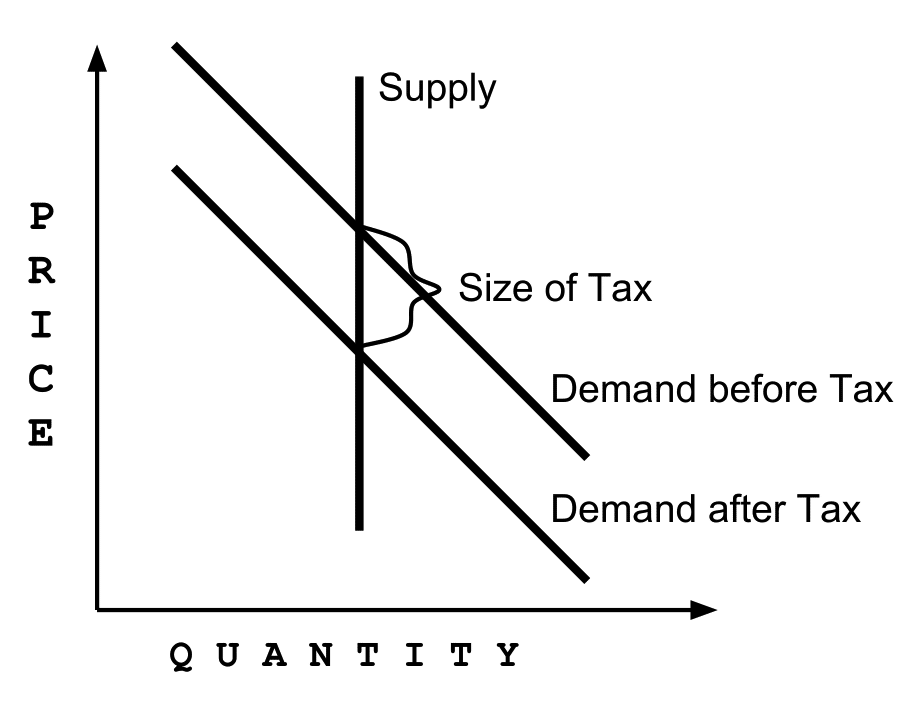

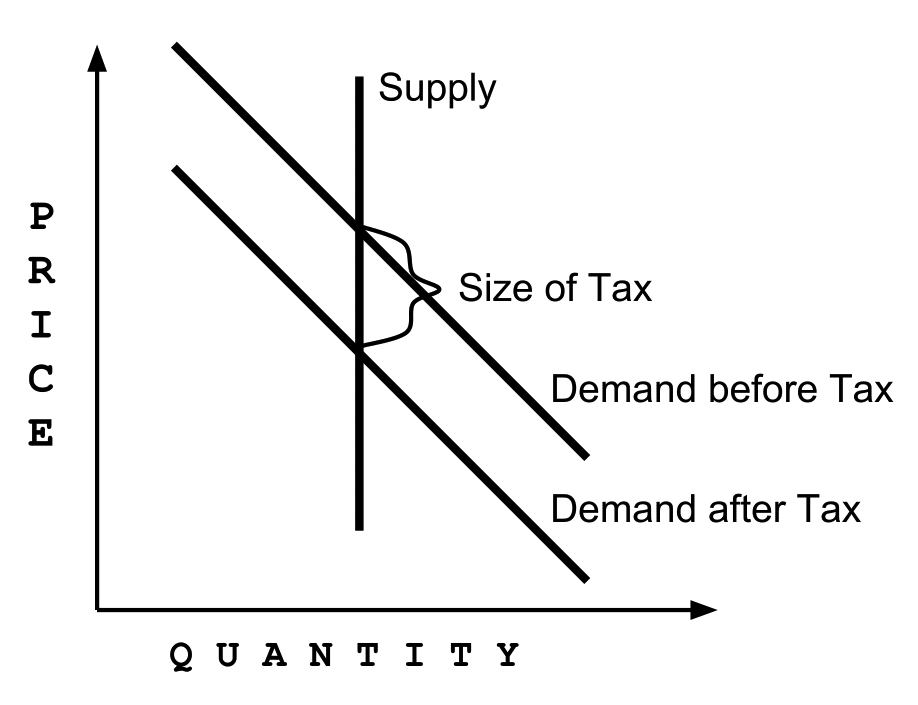

Land was sometimes defined in classical and neoclassical economics as the “original and indestructible powers of the soil.” Georgists hold that this implies a perfectly inelastic supply curve (i.e., zero elasticity), suggesting that a land value tax that recovers the rent of land for public purposes would not affect the opportunity cost of using land, but would instead only decrease the value of owning it. This view is supported by evidence that although land can come on and off the market, market inventories of land show if anything an inverse relationship to price (i.e., negative elasticity).

While it’s appealing to say ‘if you want less of something, tax it,’ this rule doesn’t apply to inelastic goods. By definition, the supply of an inelastic good can’t be reduced with taxation. (In fact, if a good has negative elasticity, taxation would actually increase supply.)

My assertion about inelastic land supply fits with common experience. Cities with high land values usually see less development. Cities with lower land values may experience a lot of development (e.g. Austin), or none at all (e.g. Detroit). There are only two possible explanations for this: either the supply of land is inelastic, or the price of land has little overall impact on the supply of housing.

To distinguish or not to distinguish: stories about ‘the market’

Bertolet’s overall argument rests on a theory suggesting that the supply of land is elastic. Yet he admits that much of the land in Seattle is actually inelastic:

“The first piece of evidence Pickford presents to make the case that the factors I describe above would not impede housing development is historical data showing that the number of homes and condos for sale in Seattle is not influenced by average sales price—that is, people aren’t more inclined to sell their homes when prices are high, and vice-versa. However, most people who are selling homes live in them, and therefore most will be purchasing (or renting) another home in the same housing market with the same price trends. Therefore it makes all the sense in the world that sales price wouldn’t effect [sic] sales volume—for homes.” [emphasis mine]

Most urbanists would like to see more urban spaces, which means urbanizing (or redeveloping) single-family zones. If Bertolet’s description above is correct, then his argument against linkage fees does not apply to these zones.

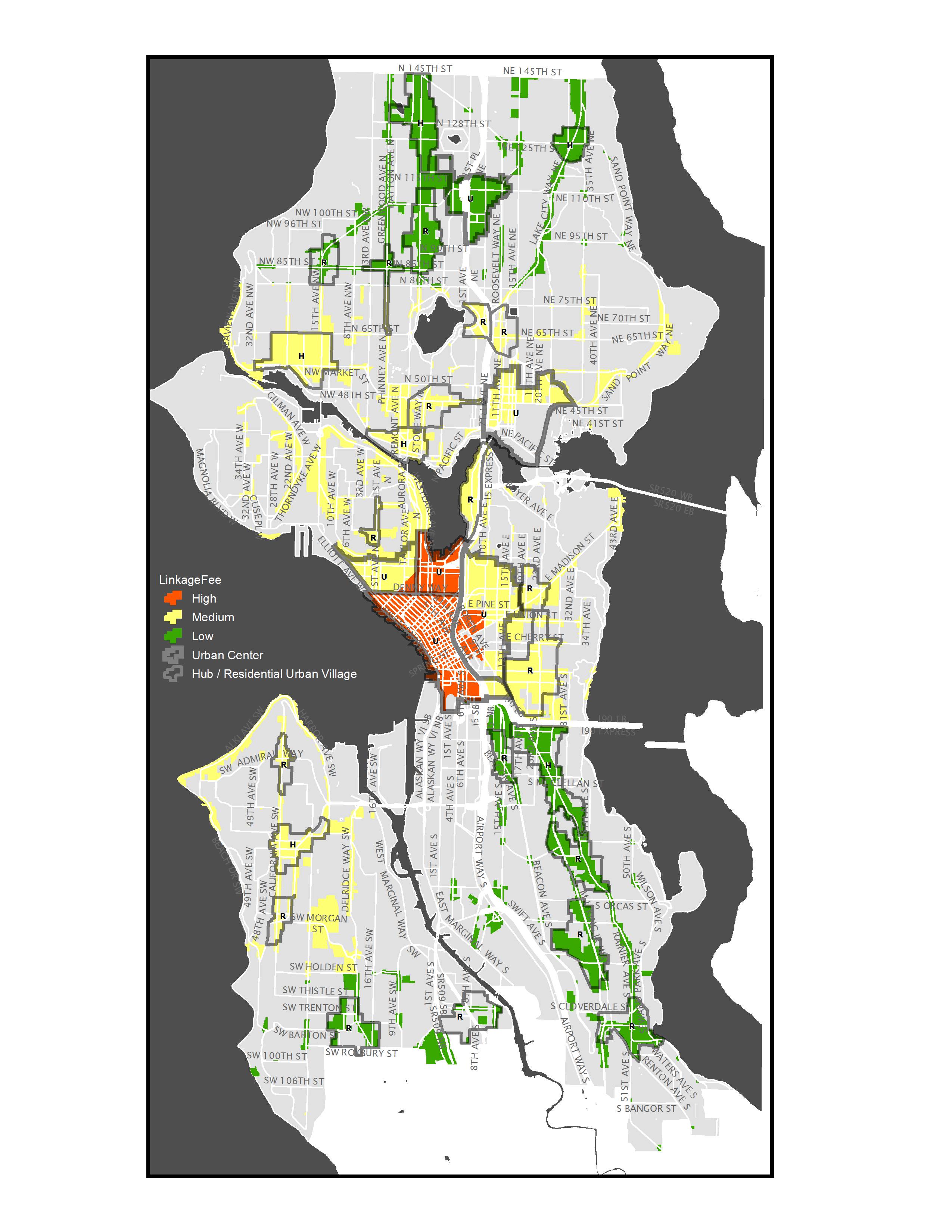

Bertolet goes on to suggest that land with existing uses besides homeownership is elastic; in these areas, lower land values decrease the supply of land. (Conveniently, this definition seems to include everywhere that linkage fees are proposed, even though many of these areas are full of owner-occupied homes.)

By definition land is inelastic. Clearly, the total amount of land in Seattle is not changing. Instead, Bertolet muddles the discussion by suggesting the supply of land varies as land comes on and off the market. Since the value of land in cities is derived from development, it’s not clear what land coming off the market means. A commodity like salt can be put to multiple uses. If restaurants have less need for salt, then more salt might be used to de-ice roads, or producers might make less. But landowners can’t shift land to a different market or reduce production. If land is not on the market for development, it has no value. In other words, in order for a good to be elastic, the production or use must change.

I would argue that Bertolet’s analysis confuses whether or not land is on the market with whether or not a seller is willing to sell. Fortunately, landowners can’t capture the value of this asset without selling it. (Earning an income on a property is an alternative, but this is a distraction.)

Why land doesn’t keep its current use

Suppose that you owned a rental property that earned $1,000 a month in rent. How much would someone have to pay you to sell your property? You would probably need more than $1,000, since you could wait a month to collect that amount. Yet, while you might accept a higher offer, you probably wouldn’t require more than $1,200,000 (100 years’ worth of rent). It’s unlikely you will live that long, and your only alternative beyond collecting rents is to sell the property. In fact, the number is likely much lower than this; the property will depreciate, and money now is worth more than money in the future. Going even further, if a seller can reinvest the money from a sale on something that has a better return and/or earns more income, nearly any sale price would be tolerable.

But what is a buyer’s willingness? In the case of developers, the amount they are willing to pay is likely well above any amount required by a seller. Unlike a landowner, developers seek out the lowest risk, highest return properties. These properties are generally ones that can be better utilized. For example, developers might target a property with a one-story building in a zone that allows six stories. They don’t reach their number based on a property’s current income. Instead, they are willing to pay up to the potential income minus the costs and returns they need. In the end this means there is potentially a big gap between sellers and buyers. The seller can’t make more money at the current use, so they are generally willing to sell. Unfortunately, buyers can only make that money with the specific parcel, since land is unique. Other parcels will have different risks and returns. Developers will bid down as much as possible, but any other developer can swoop in and bid higher. The only things limiting these bidding wars are costs and expected returns. In the long run, landowners benefit. But this gap is also where costs that apply to everyone can be leveraged. So long as the seller is willing to sell after all these costs, the property is still developable.

A linkage fee is an added cost, but one that’s unlikely to affect sales. As an example, the highest possible linkage fee on the sale of the Sunset Electric parcel would have been $1.3 million. That’s a lot of money for affordable housing. But would the landowner still have sold the property? Records indicate the landowner would have made $2.5 million after the fee. This is about 100% profit on a six-year investment.

There are even further factors working against existing uses. Property depreciation ensures that income reduces over time. Market risks like the 2008 recession prevent people from simply holding on to land and being guaranteed a higher return. Information asymmetry helps developers who can take their capital to other places but hurts landowners with no other options for cashing out their asset. GMA laws require periodic upzones that increase potential uses beyond the current income. And, of course, the inevitability of death means that people’s need to sell will increase over time. I don’t want to pretend that I know the reason why land is inelastic, but all of these reasons are plausible explanations.

Market Stories And Market Evidence

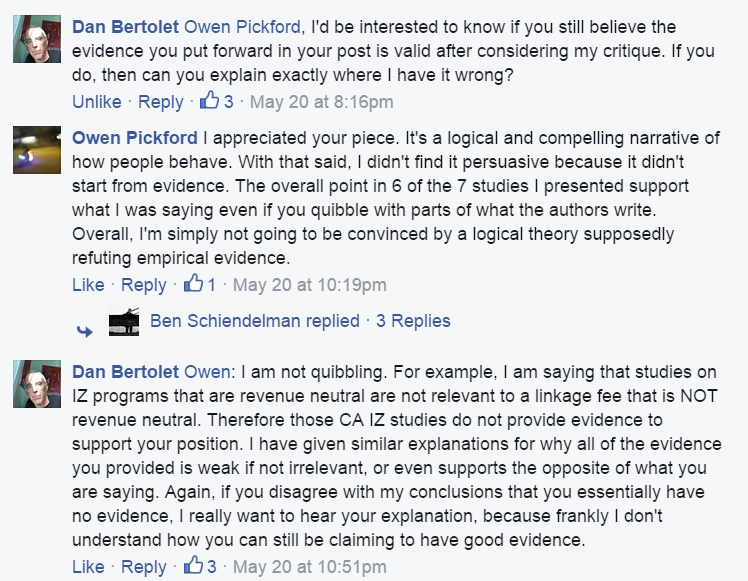

Overall the distinction between different types of landowners relies on a story rather than evidence. Some have argued this is a stronger argument. I remain unconvinced, preferring to side with the central findings of the empirical evidence. (We suggested some empirical evidence that might buttress Bertolet’s argument, but he didn’t provide it.)

Instead of providing evidence the rebuttal dismisses an article by Michael Goldman using Seattle data, demonstrating land inelasticity. In an effort to produce more evidence, I wondered about the distinction made in Bertolet’s rebuttal. Are income earning property owners different than homeowners? Does income from an asset change the way people treat that asset? It seems a stockholder earning a dividend would be a good comparison to an income earning property owner. Yet the evidence doesn’t seem to show a correlation between price and trade volumes for stocks that earn dividends.

Again the rebuttal article only draws a distinction between homeowners and income-earning property owners. I think this distinction is a red herring. The difference isn’t as stark as one might think. Homeowners earn imputed rents, making them similar to income-earning property owners. Weighing the sale of a property against the income isn’t an unreasonable thought experiment, but shouldn’t homeowners make this judgement too? To be clear, homeowners buying and selling in the same market is evidence of land inelasticity. They remain in the same area because land is unique based on its location. Even Bertolet indicates twice in his rebuttal that parcels are unique, a characteristic of an inelastic good.

The rational market actor described in the rebuttal, often called an econ, is an archetype and should be viewed skeptically. Even if we accept that framework, there are huge segments of property owners in Goldman’s evidence that are income-earning, namely people who rent their homes. Beyond those people there are others that should maximize the return on their property. Retirees should wait to get a bigger nest egg. Couples downsizing – perhaps from two homes to one home or when their kids go to college – have flexibility on when they sell. People moving out of the regional market will need to buy in a new market. In fact, I have a hard time imagining many homeowners not trying to maximize their largest asset. I would expect a group this big to affect the data. Yet, despite all this, the data still indicates land is inelastic. And most importantly, Bertolet doesn’t present any data supporting his assertion.

Wikipedia goes so far as to say evidence shows negative elasticity. There are even logical explanations to explain why land has negative elasticity. Most likely urban land is a safe, high-return asset and landowners are monopolists. A high price indicates a low-risk asset, worth keeping for its rental income. A low price signals high risk and the possibility to earn better returns elsewhere. It makes sense to hold on to urban land if the return versus risk calculation is very good. If that calculation persists, factors other than price will likely cause sales. In other words, land supply is inelastic.

Debate about the elasticity of land is important but actually unnecessary. It’s pretty easy to determine that linkage fees won’t affect the supply of housing even with an assumption that land is elastic. In the next article, I’ll try to engage charitably with Bertolet’s arguments by accepting his premise but still show linkage fees wouldn’t reduce housing supply.

Better Regulations And Fewer Housing Limits

In summary, I want to repeat my initial call for urbanists to focus on housing limits, rather than regulatory costs.

It’s critical that urbanists’ goals to build more housing don’t prevent the city from being successful. Bertolet’s article completely ignores the progressive desire to create mixed-income neighborhoods and equitable access to urban benefits. We shouldn’t avoid these and other desirable outcomes in service to a theory about regulatory costs. Instead, if we are convinced that there is some cost from an otherwise beneficial regulatory change, urbanists should focus on mitigating those costs. The most obvious way to mitigate the perceived cost of linkage fees isn’t to fight with affordable housing advocates. It’s to argue for upzones.

I don’t mind opposition to linkage fees. I was actually surprised by the widespread positive reception to the argument in favor of linkage fees. I hope the discussion continues and there is some new empirical evidence presented. Most importantly, though, I encourage urbanists to seek out empirical evidence and to distinguish the efforts to eliminate regulations from the fight to eliminate housing limits. Seattle doesn’t need less regulation, it needs better regulation, and ultimately fewer housing limits.

Owen Pickford

Owen is a solutions engineer for a software company. He has an amateur interest in urban policy, focusing on housing. His primary mode is a bicycle but isn't ashamed of riding down the hill and taking the bus back up. Feel free to tweet at him: @pickovven.