Over the past few years a convincing narrative emerged explaining high housing costs in cities. As the narrative goes, urban housing is expensive because supply doesn’t meet demand; therefore, we need to build more housing to bring down prices. This view is bolstered by writers like Ed Glaeser (The Triumph of the City), Matthew Yglesias (The Rent Is Too Damn High), and Ryan Avent (The Gated City), each making compelling arguments for removing limits on housing in urban areas. Glaeser argues that laws regulating additional housing are directly correlated with changes in housing costs, including laws restricting building heights. Yglesias claims that limits on housing are blue America’s biggest failure. Avent goes so far as to claim that America’s economic stagnation can be attributed to housing regulation.

It’s true that expensive cities need a lot more housing. However, this narrative overlooks the differences in regulations affecting development. Specifically, it doesn’t differentiate between regulations like height and density limits, which prevent new housing, and impact fees or design review, which raise the cost of housing production. The former are limits on housing. The latter are regulatory costs.

Seattle urbanists often conflate additional building costs with limits on housing; frequently suggesting that regulatory cost, not housing limits, are the biggest impediment to affordable housing. The result of this mistake has been detrimental to urbanists’ goals, creating an adversarial relationship between urbanists and affordable housing advocates. Furthermore, blurring the lines between housing limits and regulatory costs induces urbanists to overlook the most important factor in housing affordability: land values.

This article will first show that linkage fees are misunderstood because the relationship between land values and regulatory costs is either misunderstood or overlooked. It will then show that land values are the root cause of the housing affordability crisis and linkage fees, a form of inclusionary zoning, are a unique tool to ameliorate this crisis. It will then address urbanists’ objections to linkage fees and provide empirical evidence showing that linkage fees produce affordable housing without reducing the supply of market rate housing. Finally, I will present the political reasons urbanists must support linkage fees.

Land Economics: Where Does Land Value Come From & How Does Regulation Affect It?

The Urbanist has covered land value theory before. To summarize, the price of land is connected to the amount of revenue that land can generate. If land can generate more revenue, land is worth more. Economists call this revenue ‘rent.’ Sometimes, rent is direct, like the money that a landlord receives from tenants. Other times, it is implicit, like the rental payments a homeowner avoids from owning their home. Earning more income from land often requires additional costs, such as constructing a larger building, but the greater potential income that results from those costs is reflected in greater land values. The value of land is determined by the relationship between potential income and costs. This is an old concept that has been well demonstrated:

The law of rent makes it clear that the landowner has no role in setting land rents. He simply appropriates the additional production his more advantageous site makes possible, compared to marginal sites. The law also verifies the claim by Adam Smith that the landowner cannot pass on the burden of any cost such as land value taxes to his tenants.

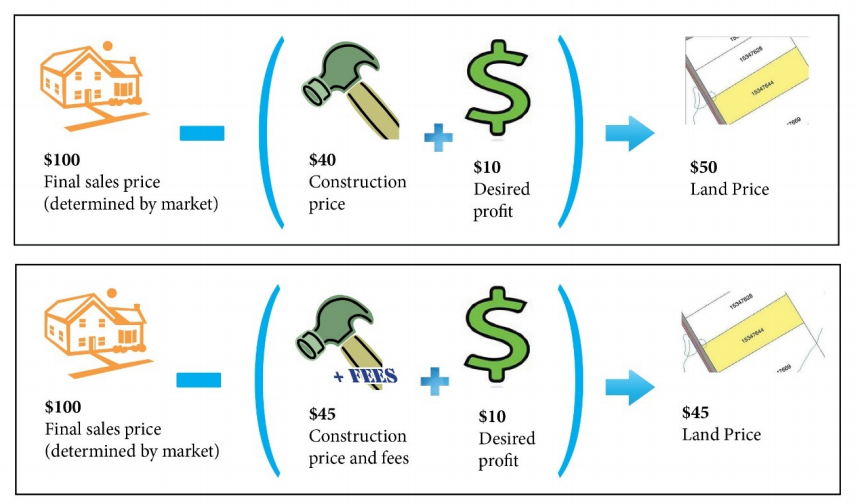

Perhaps most importantly, anything that reduces economic rent — e.g. regulatory costs, permitting, design review, etc. — also reduces land value by a corresponding amount.

This is why it’s wrong to suggest that regulatory costs are the same type of impediment to additional housing as development limits. Because of the unique nature of land, regulatory costs reduce the value of land while development limits create a ceiling for land value. If regulatory costs were reduced, would developers build more housing? Probably not. Would developers make more money? Again, probably not. Instead, landowners would recognize the land’s potential income and, in the long run, landowners would charge developers more for land. Regardless of the rent for apartments or the demand for housing, developer profits are relatively steady.

This is the most important concept for urbanists to understand: Development costs, including regulatory costs, drive down the value of land; development limits determine the ceiling of land value. Understanding this concept allows urbanists to see that reducing regulatory cost benefits landowners, not developers or renters. Alternatively, upzones produce more housing, indirectly benefiting renters, but also increase land values, massively benefiting landowners.

Piecora’s: Insane Profits With Virtually No Effort

Most of the income from higher rents flow to landowners, which is why landowners make a killing during urban construction booms. A great example is Piecora’s on Madison. Not too long ago Piecora’s sold for $10.29 million, not because their pizza is delicious but because the land beneath the pizza shop is valuable.

The developer who bought Piecora’s will invest in the neighborhood, add improvements to the lot, earn a modest profit and be pilloried by neighbors for closing a favorite business. Meanwhile, the landowner (who also owns Piecora’s) will abandon the business and make a 250% profit, over $7 million, simply by being at the right place at the right time.

This is urban land economics, but it raises an important question: Why does value flow to landowners instead of developers?

Why Money Flows to Urban Land Owners

It’s been shown that Walk Score is a decent proxy measurement of value. But what does this mean? High Walk Scores indicate proximity to desirable characteristics: Transit, grocery stores, schools, jobs, bars, restaurants, people and opportunity. I will call the sum of characteristics that make city-life enjoyable urban benefits. A higher Walk Score means more urban benefits in close proximity. A parcel of land close to many urban benefits is a desirable piece of land. This desirability means landlords can charge more for housing and people will pay more.

The space available in proximity to urban benefits is fundamentally limited, and this limit creates a hierarchy of desirable housing. It’s possible to create more neighborhoods with more urban benefits, but this takes time and a massive amount of investment. Many places solve this problem by living more densely or improving transit, so that more people can access urban benefits. However, there are diminishing returns on transit investment and living more densely. In Seattle, many areas in close proximity to urban benefits only allow detached, single-family homes, limiting access to urban benefits until upzoned.

In fact, as we expand upzones and urban benefits in Seattle, more places will increase in desirability and will experience land values increase. Places with high land values in proximity to locations with increasing urban benefits will see land values increase even further. In other words, adding urban benefits reinforces the hierarchy of desirable housing. This is the fundamental logic of why rents and land values decline from the center of a city outwards. Furthermore, this explains why zero-based zoning does nothing to address housing affordability; it doesn’t reduce or change the hierarchy of desirable housing.

The fundamental insight to understand is that because each parcel has unique value, landowners command a monopoly on their location. A piece of land within walking distance to a subway station is fundamentally different than one within walking distance to a bus stop. Developers compete among each other in an open market against monopolist landowners who extract all of the value (up to the point that development would no longer make sense). Ultimately, the worth of urban benefits flows to landowners.

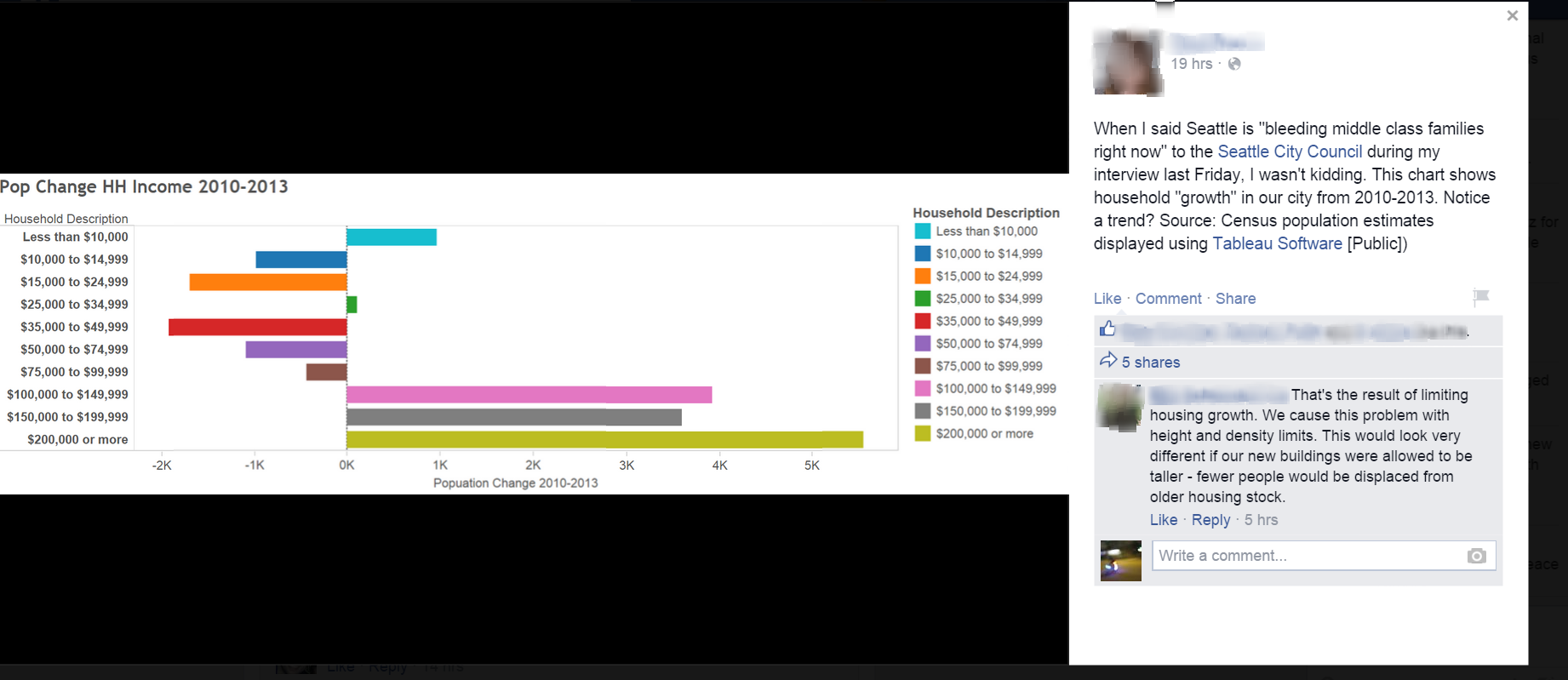

Perhaps the most enraging aspect of this equation is that the additional value landowners are gaining is largely contributed by the public. Tax dollars invested in transit, fire, police, schools and much more create most of this value. There is even tremendous value gained simply when people live near each other, whether it is from access to social interactions or to professional opportunities. In the end, we all create value. This value creates desirability, increasing rents and creating higher land values and a hierarchy of housing choices. The end result of this hierarchy is segregation. Those with less money end up in areas with fewer urban benefits.

Seattle is currently investing in a subway system and the lucky landowners next to future stations won the lottery; a public investment turns into a massive private profit and the city suffers due to higher rents and segregation.

The Root Causes Undermining Efforts For A Better City

I’m not opposed to people making a lot of money out of sheer luck. It doesn’t seem completely fair, but it’s wrong to begrudge others’ luck. What should be vilified is unearned profit that creates misery. This is the dynamic of urban land values. The urban land market exacerbates four problems:

- Developers appear to profit from construction when it’s actually lucky landowners making bank

- Renters experience increasing land values through increased rents

- Increasing land values make it difficult to maintain mixed-income neighborhoods

- Increasing land values create diminishing returns on subsidized housing

Developers appear to profit from construction when it’s actually lucky landowners making bank:

The first point is one that anti-development advocates latch onto in their efforts to demonize construction. Occasionally, land doesn’t capture the value of rents. Risk-taking developers sometimes gamble on possible rent increases by paying the current market value of land, building fancy apartments, and then advertising them with high rents. If they are able to fill the apartments, they will make a killing. If they aren’t, they’ll face a loss. But this is the exception, not the rule, and many developers lose money taking this gamble. Unfortunately, once one developer gambles and wins, land values adjust accordingly and the next developer must pay more for land. In the long run, developer profits are actually steadier and mostly independent of the rent tenants pay. Most developers profit by minimizing the risks involved with building and investing in a neighborhood, not by charging exorbitant rents.

Unfortunately, neighbors see new construction with higher rents and associate this with developer profiteering. Developers take the political heat while landowners laugh all the way to the bank.

Renters’ lived experiences tell them that development increases rents:

Development does often lead to displacement. Land values increase as higher rents become possible. On a hyper local level, this likely means a property tax increase. Since a landlord is largely in the business of managing operations, nearly all the increase in property taxes are passed on to renters. Most urbanists argue that these costs would be worse if more housing weren’t built, and they’re right. But this response does nothing to actually solve the problem or address the lived experience of renters. This lived experience creates grassroots opposition to new development.

Increasing land values make it difficult to maintain mixed-income neighborhoods:

All of which leads to the third point. If new neighborhood development is charging substantially more than old development, an area will likely see a boom in construction. Developers buying land have to pay increased land prices, reflecting the expectations for higher rents. Because of the upfront land cost, it becomes nearly impossible to build lower-cost units without subsidy. Any unit priced below the market rate causes a loss for the developer. This is why new development in cities is expensive, while new development outside cities can be accessible to middle-income earners. This is also why many solutions suggesting we can build below-market housing without subsidy don’t pencil out. Landowners know the market rate for rents and sell their land accordingly. In the end, neighborhoods end up with rents that are all similar and become economically segregated. This economic segregation is at the heart of the housing affordability crisis. It’s important to note that most cities have affordable housing somewhere. The real problem is that particular neighborhoods are unaffordable and economically segregated.

Additionally, this segregation has a huge impact on individuals lives. New research looking at millions of families over long periods of time indicates that proximity to urban benefits is incredibly important. The research shows that children growing up in better neighborhoods earn more, experience better health, are more likely to attend college, and generally have a better life. An economist writing on these findings says:

…the relentless accumulation of evidence is now so compelling that I believe it will sustain a new consensus. That consensus, simply stated, is that place matters.

Segregation from rising land values eliminates access to better neighborhoods for people lower on the economic ladder. It’s not an exaggeration to assert that access to urban benefits is deeply connected to many intractable, national problems.

There are diminishing returns on subsidized housing:

Lastly, many urbanists’ preferred method to achieve economically diverse neighborhoods is insufficient. Rising land values make it increasingly difficult to provide subsidized housing in the long run. Many people think a larger housing levy or state trust fund is the simplest way to support subsidized housing. This overlooks the role of land values. In areas needing the most subsidy, land values are often the highest and fastest growing portion of costs. Without intervention, land values will continue to increase and over time, it will take more dollars to provide the same number of affordable housing units.

History, Economic Morality and the Big Picture

Henry George is perhaps the most famous person to write about the unique nature of land. He became well known in the late 19th century advocating for a land tax on the unearned value accumulated in land. George made both a moral and practical appeal for this tax. First, he saw it morally superior to other taxes because the wealth from the value of land is not wealth that is earned through effort. In other words, it is unfair for a Seattle landowner to get rich because the public invests in a light rail station. Additionally, George understood classical economics. When most goods are taxed, the price of the good increases, reducing the demand and consequently reducing the supply to match the reduced demand. This is called ‘elasticity.’ Strangely enough, land is not such a good. Taxing land doesn’t reduce the amount of land in the world. Land is (for most purposes) perfectly inelastic.

Housing costs in modern cities present the most stark examples of wealth without effort. Currently, cities across America have vast plots of unused land, largely in the form of parking lots. These plots remain unused because landowners are speculating on the value of their land, minimizing operational costs in order to hold the land longer. When they think the value peaks, they’ll sell. Massive fortunes are amassed on this strategy. There are publicly traded companies that depend on under-utilizing our cities; effectively harming all the residents. A land tax increases operational cost, forcing landowners to make a choice to utilize their land and collect income or sell the land.

George’s idea was so influential that many economists even today consider land taxes the most moral and effective way to raise revenue. This idea is also very popular with urbanists (see Sightline Institute for a great rundown of this) because it results in better land use. Urbanists support a regulatory cost on housing.

Concerns about land values are making a comeback, and land value taxes deserve more attention because they may eliminate some of the biggest problems in urban areas. Recent examples such as commentary decrying the surge of foreign capital into urban real estate are likely the result of land value speculation. How large is this problem? Perhaps the best response to Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the 21st Century is an analysis that looked at what types of capital are appreciating. The biggest finding suggests that increasing wealth from capital is largely due to housing.

In a country where urban land makes up most of the value of land, the rising value of housing is likely due to rising urban land values. So what is the connection to linkage fees? Put simply, a land value tax would recapture the unearned increase in land values. It would also discourage speculation. A linkage fee would likely have many of the same effects, capturing land value increases for public benefit and decreasing the return on land which should discourage speculation.

Linkage Fees Are Inclusionary Zoning: An Essential Tool Of Housing Affordability

The term ‘inclusionary zoning’ is derived from the long battle to end exclusionary zoning practices. Exclusionary zoning laws were designed to purposely exclude groups of people from neighborhoods, usually racial minorities. These laws included racial covenants, redlining, and many other practices that are responsible for the segregation we still see in our cities today. To overcome this and meet the promises of the civil rights movement, activists began pursuing inclusionary zoning. The first instance of inclusionary zoning was implemented in Montgomery County, Maryland, a racially and economically diverse suburb of Washington DC.

Inclusionary zoning laws vary widely but generally require private developers to include a certain number of affordable housing units in new development. A municipality might require that 5% of all units in new buildings be affordable, perhaps by lowering rent to less than 60% of AMI. There are often opt-out clauses that allow developers to pay a fee instead of building units. The fee goes to the municipality and is used to build affordable housing. Seattle’s linkage fee policy would require developers to pay a fee or opt out by building affordable units. The linkage fee would act like an inclusionary zoning ordinance.

Inclusionary zoning was invented to produce affordable housing and help integrate communities. It is scalable by design, increasing the costs of development as well as affordable housing in proportion to the amount of total housing built. But the policy adds a critical benefit beyond building units and integrating neighborhoods; a benefit not seen in other affordable housing tools. It passes regulatory costs to landowners, throttling land value increases. Overall, inclusionary zoning captures some of the increasing land values in a growing city to produce affordable housing and economically integrated neighborhoods, value that otherwise would increase rents to profit landowners. As we will show later, it does all this without reducing the amount of housing built.

Dissipating The Problems Undermining Development

If you acknowledge the evidence that regulatory costs are passed to landowners, linkage fees will effectively solve the problems that undermine building a better city. Most importantly, they will create a political dynamic that will encourage more development.

Developers appear to profit from construction when it’s actually lucky landowners making bank:

New construction and upzones will create affordable housing. Everyone will know that new development is building more affordable units and private developers will get the credit. This is done by reducing landowner profits but it will appear as if developers are using their money to make a better city.

Renters’ lived experiences tell them that development increases rents:

With linkage fees, the lived experience of renters becomes very different. As developers calculate their costs and needed returns, they bid less on land and landowners can no longer make a killing. This means that increases in property values will be more uniform across the city. Existing buildings in neighborhoods with construction won’t see as steep property tax increases. Consequently, renters in existing buildings won’t see rents spike due to property tax increases. The lived experience connecting development to increasing rents becomes much different.

A desirable city finds it increasingly difficult to support mixed-income neighborhoods due to high land values:

Linkage fees necessarily require new construction to be mixed-income. This won’t be a panacea for segregation, but it will go a long ways towards resolving inequities. This is something that won’t happen without government policy. Without market intervention, there will always be a hierarchy of housing desirability, a hierarchy of costs, and segregation. Many of the oldest, most intractable problems in our cities and country are connected to segregation. Currently, the overwhelming solution is to subsidize people to live where they want. This is expensive, reducing the number of people receiving subsidies. It has also shown extremely limited success.

There are diminishing returns on subsidized housing:

Linkage fees avoid the diminishing returns on subsidizing the construction of affordable housing. The amount of housing is scaled to the growth of the city. If the city is experiencing a boom, more affordable housing will be built. Rather than taxing people and using those dollars to buy diminishing amounts of land and produce less and less housing, linkage fees always produce the same amount of housing relative to the amount of development. Additionally, since it slows the growth of land values, trust fund dollars go further.

Linkage fees are a policy tool that unites urbanist constituencies:

Most importantly, this type of policy will align the interest of affordable housing advocates, developers, environmentalists, and renters. In order for linkage fees to produce affordable units, an area has to encourage private development. This means development limits, such as single-family zones and height and density limits, hinder the production of affordable housing. The arguments made by anti-development advocates are persuasive because development increases land values, displacing residents. By disconnecting these two mechanisms, anti-development advocates will be marginalized. Furthermore, urbanist political constituencies will have an incentive to eliminate housing limits and encourage development. When private developers build affordable housing, new construction becomes the path to a better city.

Addressing Urbanist Concerns

The linkage fee proposal in Seattle has been mocked and vehemently opposed by many Seattle urbanists. Some Seattle urbanists, including the Downtown Seattle Association, even pursued a lawsuit to require an environmental impact study that might prevent the fees. The lawsuit targets the process, but is intended to obstruct the policy. Additionally, a group that includes Vulcan, one of Seattle’s largest urban landowners, is developing opposition to further regulatory costs.

Opposition to regulatory costs are the result of conflating regulatory costs with development limits and misunderstanding the effects of regulatory costs on land values. If urbanists understood the theory of land economics and looked at the evidence, they should come to the conclusion that linkage fees will not reduce development.

To address Seattle urbanists’ concerns it’s necessary to understand that they believe increasing the number of people who choose to live in the city is paramount. They know the benefits of urban living are huge. Many more people would live in the city if they could find acceptable housing at the right price. Most urbanists have the goal of building as much housing as possible.

With that in mind, urbanists’ opposition to linkage fees usually falls into one of these five categories:

- Increased development cost will be passed on to renters, increasing rents

- Increased development costs will make some projects unaffordable, reducing production

- Even if increased development costs are passed on to landowners, fewer landowners will sell their land at a lower price, reducing housing production

- It’s unfair to put the burden of providing affordable housing on developers

- Why spend all this energy and effort on linkage fees when we can focus on building enough housing to drive down prices?

To begin addressing these concerns, it’s important to understand that there are only three possible reactions to linkage fees: The added costs could be eaten by the developer, passed on to the renters, or passed on to the inputs for development, most likely the land. Any outcome that doesn’t reduce the production of market rate housing but does increase the amount of affordable housing would be a win for most progressive Seattleites and urbanists. For that reason, I will focus on whether or not any of the objections reduce the amount of housing built.

Increased development cost will be passed on to renters, increasing rents:

This hypothetical outcome is not how the rental market actually works. Landlords can’t set rents according to development costs. Rents are determined by the relationship between the supply of housing in a market and the demand for that housing. If the supply/demand relationship allowed for higher rents, landlords should already be charging more regardless of linkage fees. Linkage fees can’t affect rents unless they affect the supply/demand relationship and I’ll address the supply issue shortly. Lastly, if developers resolve this problem by passing the fees to renters it means there is no reduction in housing construction.

Increased development costs will make some projects unaffordable, reducing production:

This hypothetical also misunderstands how the market works. Developers would seek to lower their costs before giving up. This logic is demonstrated in Vulcan’s quarterly survey predicting that linkage fees would likely reduce bids on land. Developers that do nothing, sitting on their capital, would not be rational economic actors and would lose market share to developers bidding less on land. Ultimately, the same amount would be built as developers bidding less gained more market share. This article will later show that supply is not constrained which means developers don’t stop building projects. This leads to the next objection, what happens if developers bid less on land?

Even if increased development costs are passed on to landowners, fewer landowners would sell their land at a lower price, reducing housing production:

If bids on land decrease, won’t landowners sell less land? This objection is most clearly aligned with classical economics but it misunderstands the unique nature of land. The answer is a definite ‘no’ and this is because land is perfectly inelastic and heterogeneous. In fact, even Smart Growth Seattle points us to evidence that linkage fees don’t constrain supply; that is, the fees don’t constrain the amount of land that landowners sell. Other urbanists have begun to state this fact as well.

And this makes logical sense when you consider that landowners treat their land like an asset. When all developers bid lower on land, landowners can’t convert their land to some other economic good or take it to a different market. They don’t sell more when their land is more valuable or less when their land is less valuable. In fact, there might even be a negative relationship between land sales and values, in which land sales increase as land values drop. This is because the decision to buy or sell an asset is based on expected future value, not current value. If you expect your land to increase in value, then it makes sense not to sell it. The inverse is also true. In fact, linkage fees may have a significant effect on land sales; as the fees are implemented sales should accelerate because landowners would expect their property to become less valuable. Overall the evidence is strong and The Urbanist has made an empirical case for this, showing property values are not connected to the number of property listings.

Even if there were a stronger correlation between land sales and land prices (which, again, there isn’t), the value gained from redeveloping most properties in Seattle is so much greater than current land income that additional costs from linkage fees wouldn’t discourage the sale of land and subsequent development. Even in the case of interim use properties (a property generating income on an under-utilized lot) where the gap is smaller, income from an interim use diminishes over time and the sale value can be greatly increased with upzones. When considering the hypothetical that landowners earned nothing from selling, they would still have an incentive to better utilize their properties in order to earn more income. This suggests that land with interim uses still has a strong incentive to be better utilized. In fact, if landowners expect less money from the sale of their land, they may depend more heavily on the income from the land. This means reducing sales prices may reduce speculation and increase utilization. Lastly, the money raised from linkage fees goes back into building units, increasing the money used for development. Without linkage fees, all the money earned from Piecora’s sale left the development market.

It’s unfair to put the burden of providing affordable housing on developers:

I sympathize with the sentiment in this objection. I find it equally dispiriting that developers are scapegoats for Seattle’s problems. It seems like nothing more than a convenient, populist appeal when political leaders say we should increase developer fees. But a pragmatic solution to this problem is a solution that makes developers heroes while extracting value from landowners. Linkage fees capture the anger aimed at developers and redirects it towards something constructive. If you seriously want to change the narrative about developers, it seems logical to give everyone the impression they are building tons of affordable housing with their profits.

Why spend all this energy and effort on linkage fees when we can focus on building enough housing to drive down prices?

The final objection is usually the last resort among linkage fee opponents. It concedes the fee wouldn’t affect housing supply, would produce affordable units, and might even integrate neighborhoods, but suggests it’s a distraction from increasing Seattle’s housing stock and therefore a distraction from solving the affordable housing problem. Urbanists will typically try to refocus the conversation by saying something like, “what we really need is more developable land” or “we should have zero-based zoning.”

I agree that the linkage fee won’t solve all our problems. Even if the amount of affordable housing we build from this point on matches the nexus between growth and the need for affordable units, we would still have a huge deficit. We should absolutely focus on removing or reducing housing limits. We should absolutely advocate for building more housing.

With that said, if we only build more housing without addressing access to urban benefits we will never solve the affordable housing crisis. Higher land values make it unprofitable and nearly impossible to build new, low-cost housing without subsidy and consequently produce mixed-income neighborhoods. The hierarchy of housing desirability is reinforced the more we build. This means just building more housing increases, not decreases, segregation, rendering urban benefits inaccessible to large segments of the population. If we want a city with affordable housing in every neighborhood, we need inclusionary zoning before land values increase even further.

Second, housing limits won’t be removed simply by stating the urbanist argument more loudly. Urbanists must build political coalitions. Linkage fees unite diverse political groups in the shared interest of increasing development capacity. This political unity is exactly what urbanists need to reduce development limits.

Evidence That Inclusionary Zoning Doesn’t Reduce Housing Production

At the heart of this long argument is the assertion that linkage fees won’t reduce housing production. I’ve offered a narrative explanation and economic logic for why this is true but we should all be skeptical of logical arguments without evidence. In fact, these explanations were motivated by empirical evidence showing linkage fees won’t reduce housing supply and might even increase production. There are five academic studies examining empirical evidence about the impact of inclusionary zoning on market rate housing production. Out of these five studies, only one found a relevant negative impact. That study, published by the libertarian think tank Reason, failed to acknowledge larger market forces, drastically oversimplified its models, and could be reasonably accused of intentionally misleading its audience. You can read a criticism of the study here.

The other four studies found inconsequential or no impact on market rate housing production. The first study found the most negative evidence. The Furman Center for Real Estate and Housing Policy at New York University compared jurisdictions with and without inclusionary zoning around San Francisco, Boston and Washington D.C.

Our analysis finds no evidence that IZ programs have had an impact on either the prices or production rates of market-rate single-family houses in the San Francisco area. In suburban Boston, however, we see some evidence that IZ has constrained production and increased the prices of single-family houses. The number of affordable housing units produced under the suburban Boston IZ programs, and the estimated size of the programs’ impact on the supply and price of housing are both relatively modest.

While the conclusion may seem negative, a modest impact on single-family homes in one of the three jurisdictions, the full study indicates that this impact disappeared in 2 of the 4 models they used. Additionally, it doesn’t indicate that there was less housing produced overall.

Another study examining jurisdictions in Los Angeles and Orange County using multivariate regression analysis found no negative impacts:

Our research also suggests that critics of inclusionary zoning misjudge its adverse effect on housing supply. Contrary to the claims against inclusionary requirements, we found no statistically significant evidence supporting the purported negative effects of inclusionary zoning on housing supply.

Yet another study looked at jurisdictions in California with and without inclusionary zoning between 1988 and 2005, with surprising results:

The analysis found that inclusionary zoning policies had measurable effects on housing markets in jurisdictions that adopt them; specifically, the price of single-family houses increases and the size of single-family houses decreases. The analysis also found that, although the cities with such programs did not experience a significant reduction in the rate of single-family housing starts, they did experience a marginally significant increase in multifamily housing starts.

While this study found negative impacts, it was on the price and size of single family homes, not the supply of housing. In fact, the most statistically relevant finding was an increase in multi-family housing, the opposite of claims that inclusionary zoning reduces development and density.

The fifth and final study also found no impact on housing supply. The research examined 28 municipalities in California, some with and others without inclusionary zoning laws, between 1981 and 2001. Seattle hired the author, David Rosen, to help develop the linkage fee program.

An analysis of these data shows that for the jurisdictions surveyed, adoption of an inclusionary housing program is not associated with a negative effect on housing production. In fact, in most jurisdictions as diverse as San Diego, Carlsbad and Sacramento, the reverse is true. Housing production increased, sometimes dramatically, after passage of local inclusionary housing ordinances.

From four studies, most findings showed no impact on housing supply. Two studies found statistically relevant measures that inclusionary zoning increased supply. Part of two studies found negative impacts on single family homes, a good outcome for urbanists.

There is further evidence if we expand our scope beyond inclusionary zoning and look at impact fees. Impact fees are very similar to the linkage fee policy. The traditional view of impact fees are that they reduce housing production. Most of these views are based on old studies. Newer studies are more accurate in their measurements and have diverged from the traditional views. For example, a study looking at impact fees in Florida found nearly a one-to-one relationship between impact fees and land values:

First, we find that the difference in the effect of an additional dollar of real impact fees between new and existing housing is small and statistically insignificant. Second, although we are unable to measure the property tax savings that are expected by homeowners from the imposition of fees, we do find that higher fees reduce millage rates and the present value of the associated property tax savings are in line with the estimated effects of fees on housing prices. Finally, impact fees are found to reduce land values. (emphasis is mine) While the increase in housing prices is found to cover the current level of fees, developers purchasing land in the present have no assurance that rising housing prices will cover future fees, especially given the upward trend in total fees over time. Hence, impact fees add additional uncertainty to the development process, causing developers to reduce the amount they are willing to pay for land.

The results show that an additional $1.00 of fees … reduces the price of land by about $1.00.

Another study again broke with conventional wisdom and suggested that impact fees actually increase the amount of housing produced in areas they are applied:

The results show that non-water/sewer fees increase the number of completions of all sizes of homes within inner suburban areas and medium-sized and large homes within outer suburban areas.

This is likely due to the reduction in land prices and the increase in demand due to urban benefits built with the fees.

To sum up, we have one study from an ideologically-driven organization suggesting some negative effects of inclusionary zoning, four studies in peer reviewed, academic literature demonstrating at least no impact on market rate housing production and possibly an increase. The economic theory and empirical research point in the same direction. Inclusionary zoning doesn’t reduce housing production and might even increase it.

The Political Landscape For Urbanists Going Forward

I was initially opposed to linkage fees. I began to doubt this view because the most urbanist politician in Seattle proposed the policy and it was supported by affordable housing advocates. It should give urbanists pause when their political views require that people who spent their careers working on housing affordability must either be willfully ignorant or actively disinterested in affordability. This seems implausible. As my skepticism grew, the urbanists’ blind spot became clear; we often conflate housing limits with regulatory costs and misunderstand land economics.

This fall, a new and drastically different city council will run Seattle. Right now, the campaigns are largely in disarray. There are more than 40 candidates and most are still forming policy positions. Still, there is nearly universal agreement; Seattle is facing a housing affordability crisis. Nearly every candidate will formulate solutions, which they will likely pursue if elected. Now is the time to push candidates for the best solutions.

Urbanists and affordable housing advocates agree that we need much more housing. Lesser Seattleites and affordable housing advocates understand land values are the largest long-term obstacle to affordable housing. Lesser Seattleites would solve this problem by lowering the ceiling on what can be done with land and advocating for housing limits. Affordable housing advocates would like to capture land value increases for public benefit and create mixed-income neighborhoods. Urbanists, following the lead of those conflating regulatory costs and housing limits, have seen little political success so far. In fact, it appears the Lesser Seattleites are a larger constituency and winning the political battle. Urbanists are faced with a choice.

We can remain the smallest voice in this debate. We can continue to conflate regulatory costs with housing limits. We can continue to ignore the problem of increasing land values. We can continue advocating only for policies that lead to displacement and segregation. We can expend our energy fighting against regulatory costs when we should be fighting for reduced housing limits. We can continue to use narratives that explain-away evidence rather than seeking to understand. We can continue to give people the perception that we are adversaries of affordable housing and integration by opposing a policy that evidence shows would be beneficial.

Or, we can expand our political constituency by joining with affordable housing advocates. This means urbanists must first support a policy capturing land value increases, and only afterwards work to remove housing limits. This also means shifting our attention away from total market deregulation and refocusing on removing housing limits.

It’s not coincidence that the Seattle City Council’s leading urbanist, Mike O’Brien, spearheaded a year-long effort to craft this thoughtful and strategic policy. The first vote on linkage fees passed 7-2 in support, but three of the council members voting in favor are retiring, and it’s not clear if a final vote will take place before the election.

The longer we wait to act, the more expensive our city gets and the harder it is to reverse. Urbanists need to be on the right side of this battle by vocally supporting linkage fees. This sign of goodwill would go a long way towards building a lasting coalition. After the linkage fee battle is won, urbanists can approach affordable housing advocates with credibility and work together to remove housing limits.

Editor’s Note: Changes have been made to the quote of the first study referring to impact fees. A number of readers responded that the study indicated impact fees increased housing prices. This is a misunderstanding of the abstract which I unsuccessfully attempted to simplify by focusing on the finding that costs are passed on to landowners. The study purposely looked at an area with impact fees and increasing housing prices in order to understand whether the two were connected. I’ve provided a fuller quote from the conclusion of the study that shows the author’s finding; housing prices increased due to lower property taxes. This is contrary to earlier studies which attribute the increase to impact fees.

Owen Pickford

Owen is a solutions engineer for a software company. He has an amateur interest in urban policy, focusing on housing. His primary mode is a bicycle but isn't ashamed of riding down the hill and taking the bus back up. Feel free to tweet at him: @pickovven.