Seattle Mayor Ed Murray, alongside his police chief and transportation director, announced last week the goal of eliminating all citywide traffic deaths and serious injuries by the year 2030. This formally enters Seattle into the worldwide Vision Zero movement, an idea originating in Sweden that recognizes traffic collisions can be reduced through better engineering, extensive public education, and coordinated law enforcement. Supporters of Vision Zero question why deaths on streets are acceptable, and tell local leaders and traffic engineers to accept that they aren’t. Local strategies will include lowering speed limits, redesigning streets, upgrading electronic traffic controls, emphasis on traffic police patrols, and ongoing community outreach about traffic laws and street safety.

Seattle is already one of the nation’s safest cities for transportation, with annual traffic fatalities at only one-third the rate of the US as a whole. Traffic collisions here have been declining even as population increases. In raw numbers, though, the carnage is still significant. In 2013, the latest year for which data is available, there were 10,310 reported collisions that seriously injured 155 people and killed 23 people. Collisions involving people biking and walking make up only five percent of annual incidents, but they account for nearly half of fatalities. There is a clear need for safer biking and walking infrastructure citywide, along with broader changes in the legal culture that often lets dangerous drivers go unpunished.

Vision Zero prioritizes efforts that slow down vehicles and prevents serious collisions in the first place, which improves safety for everyone using city streets. In a statement, Mayor Murray said, “We are rolling out a range of new safety improvements that will help get our kids get to school, reduce fatalities on city arterials and make our neighborhood streets safer. Our transportation system must work safely for everyone and this plan will save lives.” Cathy Tuttle, executive director of Seattle Neighborhood Greenways, said neighborhood advocates have been working with Murray and city staff on this for over two years.

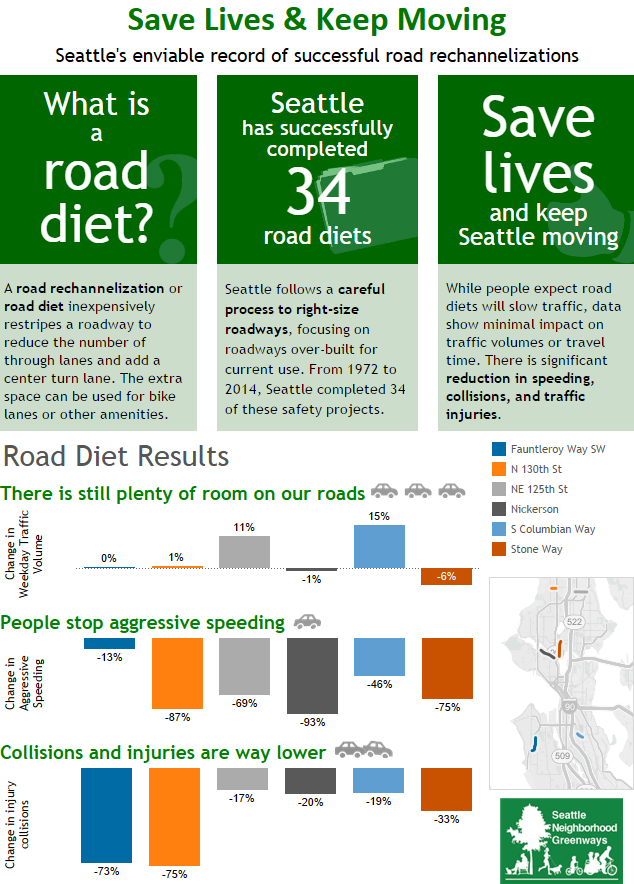

Efforts to save lives through design are not new here. Washington state adopted a Target Zero philosophy in 2000 and has been working with cities to improve safety, especially on state routes. In Seattle, an improvement project on Aurora Avenue (SR-99) was followed by a 28 percent drop in collisions, and similar work will begin on Lake City Way (SR-522) later this year. Admittedly, such efforts often don’t go far enough. But the City itself has implemented over 30 road diets over the past few decades, including on Fauntleroy Way SW, NE 125th Street, Nickerson Street, and NE 75th Street. There are several plans for improving safety on many arterials, including 23rd Avenue in the Central District and four miles of Rainier Avenue in Southeast Seattle.

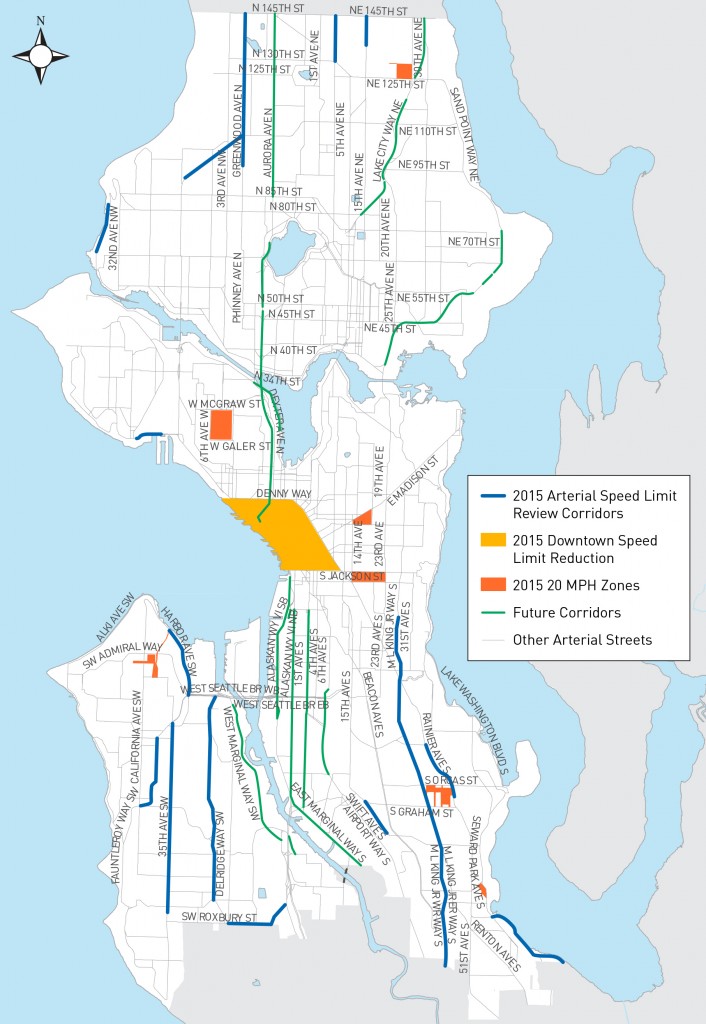

The City will continue taking a data-driven approach to street safety, noting that 90 percent of serious and fatal collisions occur on the arterials that make up 40 percent of the street network. In the near term the city will establish 20 mph zones near schools and parks. Under the mantra “20 is plenty”, Vision Zero proponents point to research showing that there is a huge difference in survivability for people hit by cars traveling 20 mph (90 percent chance of surviving) and 40 mph (10 percent chance of surviving).

Speed limits will be reduced to 30 mph or lower on a number of arterial street segments, including the downtown streets where most collisions occur. There speed limits will be reduced to 25 mph in some places, and several streets be targeted for technological and design improvements like eliminating double turn lanes, starting walk signals several seconds before green lights, and prohibiting right turns on red lights. Specific locations include intersections with 5th, 6th, and 7th Avenues between Olive Way and James Street.

In a joint letter for the Vision Zero report (PDF), police chief Kathleen O’Toole and transportation director Scott Kubly point to other cities as examples: “Better and smarter street design, paired with targeted education and enforcement is proving effective in cities that have committed to similar goals. We can learn from these cities.” New York City activists have been leading the nation on this front, and scored a major victory last year when the New York legislature authorized the city to lower its speed limit to 25 mph. Streetsblog New York has been providing comprehensive coverage on the efforts, which have also included increased ticketing for people driving cars who endanger others and installing side panels on trucks. San Francisco, Chicago, and other US municipalities and states have also adopted Vision Zero.

Seattle already has many other ongoing safety projects that support the idea, including designs for complete streets and corridor improvement projects. As part of regular upgrades, this year the City will install seven miles of protected bike lanes, 12 miles of neighborhood greenways, and 14 blocks of new sidewalks. Seattle’s Vision Zero report (PDF) says the City will continue to improve access to transit and work on safe routes to schools, coordination of construction activities with pedestrian access, and use an upcoming SDOT hackathon to look at holistic transportation solutions.

Other cities, especially in the Puget Sound region, should take note if they want to competitively attract people who wish to leave the car at home. The report declares, “We should not accept death as a byproduct of commuting. It’s time to slow down to the speed of life.”

This article is a cross-post from The Northwest Urbanist, the personal blog of Scott Bonjukian. He is a graduate student at the University of Washington’s Department of Urban Design and Planning.

Scott Bonjukian has degrees in architecture and planning, and his many interests include neighborhood design, public space and streets, transit systems, pedestrian and bicycle planning, local politics, and natural resource protection. He cross-posts from The Northwest Urbanist and leads the Seattle Lid I-5 effort. He served on The Urbanist board from 2015 to 2018.