Editor’s Note: This is Part 1 in a three-part series on measuring the success of Seattle’s urban village strategy. For the the 22 independent indicators, see Part 2 and Part 3. In this article, Scott distills down some key background details from the report.

Correction: The SSNAP report has been updated to correct statistics on where Seattle residents work. 38.2 percent of Seattle’s employed residents work outside of the city, not 62 percent.

A new report by consulting firm Steinbrueck Urban Strategies, headed up by former City Councilmember Peter Steinbrueck, details the changes Seattle’s urban villages have experienced over the past 20 years. This information will be used by planners to prepare for the next two decades with the Seattle 2035 comprehensive plan update, though the study itself has some issues.

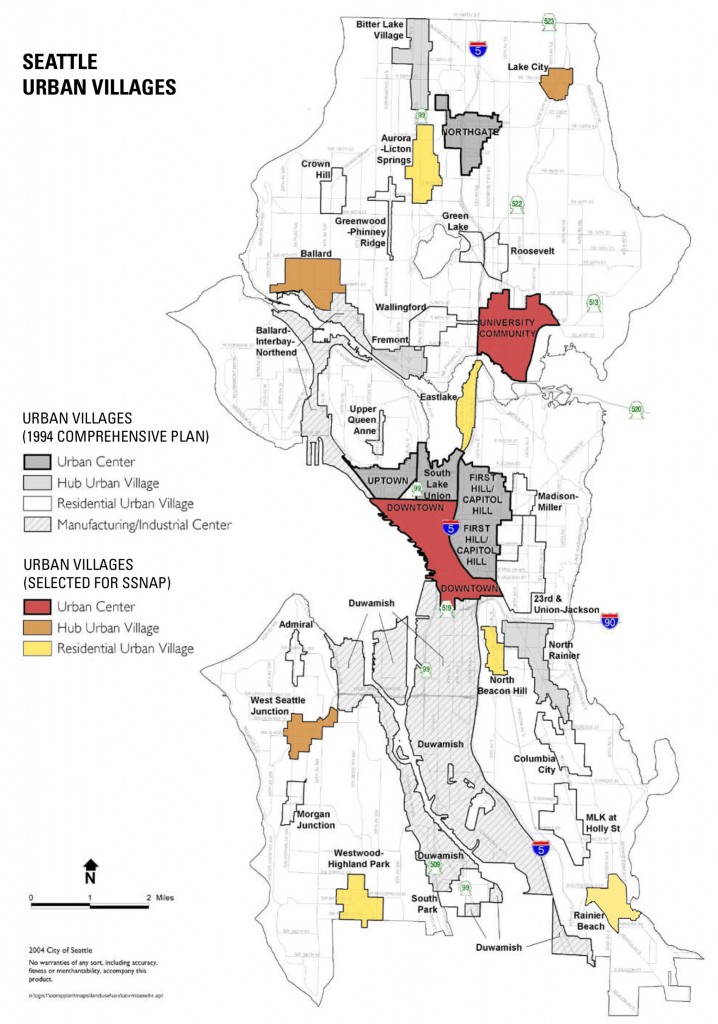

The Seattle Sustainable Neighborhoods Assessment Project (SSNAP) assesses the city’s original 1994 comprehensive plan and “urban village” strategy, which called for focusing growth in existing commercial centers. SSNAP found that, in terms of population and employment growth, the urban village concept has been successful. About 75 percent of new households and jobs in the last 20 years have been located in hubs like Downtown, Ballard, and Beacon Hill. On the flip side, public investment has not been equitable across the city’s 32 villages. And many of them are not achieving goals in housing affordability and access to education. The project aims to form lessons from the past and make recommendations for the city’s future.

Many cities are now using indicators, which are metrics that measure various aspects of civic life. Indicators are most often used as annual benchmarks to check progress towards social, environmental, and economic goals. Sustainable Seattle was the first to do so at an urban level in the early 1990s. SSNAP developed 22 such indicators in four categories: resource use and conservation; healthy communities; open space and development; and shared prosperity and opportunity.

The authors selected 10 urban villages for analysis based on geographic distribution and diverse demographic characteristics. The ten selected are, from north to south: Lake City; Licton Springs; Ballard; University District; Eastlake; Downtown; Beacon Hill; West Seattle Junction; Highland Park; and Rainier Beach. Much of the report’s data was not divisible at the urban village level, or was not available at all for certain neighborhoods. This makes clear from the get-go that the study’s methodology has limitations.

Citywide, Seattle faces the challenge of planning for 120,000 new residents in 60,000 new households over the next 20 years. The city’s goal is to balance this with 1.8 new jobs per household, and with the current balance at 1.6 this means over 180,000 new jobs are needed in same time period. Along with attracting employers, the City will need to update zoning rules to enable sufficient capacity in urban villages, which make up only a small portion of the city’s land. According to SSNAP, 69 percent of the city’s developable land is zoned exclusively for single-family homes, which means the core neighborhoods are going to become far denser than they already are. Their boundaries may also need to be expanded, spilling larger buildings into quieter neighborhoods to the delight of urbanists and the dismay of homeowners.

Another key point is that only 61.8 percent of employed Seattle residents work in the city itself. 38.2 percent commute outside of the city for employment. In an email, Steinbruck told me, “This is an important measure of regional growth management, which seeks to reduce travel trip [sic] by linking residents more closely to employment centers.” The Puget Sound Regional Council has not established any goal related to this fact in the Vision 2040 plan, which is preparing for a regional population of five million. The situation also highlights the immense appeal of living in the central city, the huge amount of employment growth in the suburbs, and the pressing need for building up multi-modal transportation systems that accommodate bi-directional commuting patterns.

To learn more about the report, you can download it (PDF) from the Seattle 2035 website or view a summary presentation (PDF).

UPDATE: The original presentation to the city and report indicated that nearly 62% of people commuted out of Seattle for employment and we reported that number here originally. This number was updated by the city and we have edited this article to reflect that update.

This article is a cross-post from The Northwest Urbanist, the personal blog of Scott Bonjukian. He is a graduate student at the University of Washington’s Department of Urban Design and Planning.

Scott Bonjukian has degrees in architecture and planning, and his many interests include neighborhood design, public space and streets, transit systems, pedestrian and bicycle planning, local politics, and natural resource protection. He cross-posts from The Northwest Urbanist and leads the Seattle Lid I-5 effort. He served on The Urbanist board from 2015 to 2018.