It’s been a bad year for Rainier Avenue South. There are the usually numerous car crashes, sure, but that’s normal. The same goes for the pedestrian collisions–regrettable, but normal. An unfortunate but inevitable side effect of the automobile, and are generally accepted with little comment.

But in April, a car slammed into a nail salon on the corner of Edmunds and Rainier, after hitting a truck making a turn. Speed was a factor, unsurprisingly, as were both vehicles attempting to beat the light. Residents grumbled; tensions rose. A temporary wall was built to replace the one torn away so suddenly, and life continued.

And then it happened again in August, when a speeding SUV lost control and crashed into the hair salon just one block south of the first such incident–this time in the middle of the day. Seven people were injured, including a family of three who found themselves pinned between the offending car and a counter at the restaurant next to the salon. The SUV was eventually dragged from its resting place, with hydraulic jacks holding the roof of the now-uninhabitable structure aloft.

Residents did more than grumble, this time. Leaders in Columbia City organized a “walk-in” rally where protestors crossed Rainier repeatedly, showing how inadequate the crossing time given was while reminding drivers to slow down. Online conversations swirled around, and it wasn’t long until SDOT amended the agenda for the already-scheduled Neighborhood Traffic Safety Meeting to include “Safety on Rainier”.

A Rainier Ave Road Diet: Proposed since 1999 1976

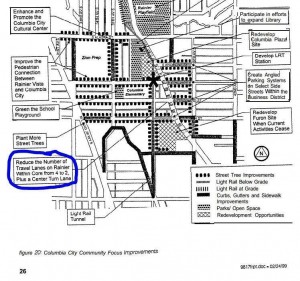

It’s a welcome addition to the conversation, and a needed one, but you’d be forgiven for recalling the sound of a broken record: we’ve been here before. The dangerous nature of Rainier is hardly new, and recent events aren’t the first to bring it to a head. Columbia City’s most recent neighborhood plan (circa 1999) envisions curtailing the road’s lanes from 4 to 2, with a center turn lane–a configuration commonly referred to as a “Road Diet”, or rechannelization in traffic engineer speak–and according to the 2008 South East Transportation Study, road diets have been “explicitly and repeatedly recommended since 1976” for various sections of Rainier.

Reducing a road’s travel lanes by half generally brings about apocalyptic predictions of gridlock and chaos, but the data shows they work. When SDOT put Stone Way on a road diet in 2007, for example, the number of cars speeding by 10 MPH or more dropped by 75%. Concerns about drivers simply going down nearby neighborhood streets proved unfounded as well: traffic on nearby streets actually dropped 12-17% post-diet. Collisions decreased too, by an average of 14%, while collisions causing injuries dropped by 33%. A later road diet on Nickerson showed even better results, with excessive speeding dropping by as much as 96%, and collisions dropping by 23%.

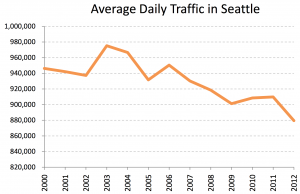

This isn’t to say that road diets are a magical solution to traffic woes–they have their limits. Studies by the Federal Highway Administration have shown that they work best on roads with daily traffic counts of about 20,000 or less. Above that number, and traffic can get excessively congested during peak periods, as anyone who has driven along N 45th St (one of Seattle’s first road diets) during rush hour can attest to.

Still, a cursory dig through the SDOT archives shows that a Rainier road diet has come up many times. Each time, including in the 2008 study (the most recent), such actions have been recommended against because they would have massively negative affects on traffic. The 2008 report was especially apocalyptic, predicting that by 2030 a road diet would cause southbound transit to run 30% slower during the evening rush hours, with car traffic running a whopping 100% slower. Despite this, SDOT’s own scoring system, along with the “Core community team” of business and community groups ranked a Rainier road diet as the most important project.

Looking at the Data

Reading into the 2008 study, though, reveals a few problems. For example, the study assumed “Only modest traffic growth on Rainier due to reduced capacity,” but in reality traffic in Seattle has been dropping drastically: SDOT’s 2012 Traffic Report (the most recent available) “notes a decreasing trend [in Average Daily Traffic] to the lowest levels this century, despite a steadily increasing population…”, mirroring national trends. Traffic levels on Rainier Ave have likewise dropped since 2008, with average daily traffic between S Alaska St and S Othello St measuring at about 19,700 cars a day according to SDOT’s Traffic Flow Maps from last year–numbers low enough to make a road diet feasible.

Additionally, the study used outdated mode choice data from the year 2000, which showed a transit mode share of only ~3%, a walk/bike mode share of only ~10%, and a driving mode share of ~87%. Such numbers are drastically out of step with the apparent mode share split in Seattle, and completely fail to take into account the massive success of Link Light Rail with regard to transit ridership, or the growth of bicycling in the city.

I’d also argue that the 2008 study failed to properly account for MLK Way and it’s reconstruction around Link. Despite being massively rebuilt with wide lanes, coordinated signals, limited turns with turn pockets where turns are allowed, and a 35 MPH speed limit, the study only assumed a “5% traffic ‘migration’ to Martin Luther King Jr. Way S. and other streets” after a Rainier road diet. Given the above characteristics, and the possibility of re-configuring the MLK Way/Rainer Ave intersection in Mount Baker to funnel traffic southbound onto MLK rather than Rainier, such a low number seems unrealistic.

Conclusion

Ultimately, though, the question of how to fix Rainier largely comes down to community values, and politics. While the data might hint at a road diet being successful between S Alaska St and at least S Othello St (if not S Henderson St), it will only happen if the community gets behind the idea, and if political leaders are willing to accept the risk of angry backlash from inconvenienced drivers. Here at The Urbanist, we think the massive benefits to safety, public health, quality of life, and socio-economic justice more than outweigh the costs–but it’s not up to us, it’s up to you.

SDOT will be hosting a Neighborhood Traffic Safety Meeting at the Rainier Valley Cultural Center on Wednesday, September 17th, starting at 6:30pm. Safety on Rainier Ave is a part of the agenda, and many expect it to be the primary topic of conversation. Join us, and add your voice!

Will became inexplicably interested in city planning, design, and urbanism after growing up in mostly-suburban Ohio. After spending 5 years living in Seattle's Rainier Valley, he relocated to San Francisco's Tenderloin neighborhood along with his wife and cat.