We’re sitting at Third and Seneca northbound on the 3, a trolley bus. The passenger in front asks me what my favorite routes are.

“I really love doing the trolleys,” I respond.

“Oh. I’ve never been on one of those,” he says. I point out that he’s sitting on one as we speak.

There may be more than one person out there who’s not entirely sure what a trolley is, or who has perhaps never ridden one. In the interest of sharing my passion for them, and in particular enlightening our far-flung readers, I’m compelled to offer some information on what exactly trolleys are, and why they’re so great.

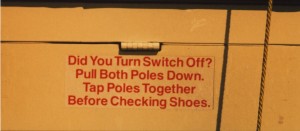

A trolley (or trolley bus, trolley coach, or trackless trolley) is a bus powered by connection to overhead wires. Poles extend from above the coach, connecting the bus to its power source. You’re familiar with streetcars and light rail, which only need one overhead wire. Why does a trolley need two? Because with rail the electrical circuit is completed by the metal rails upon which the vehicle travels. Trolley buses, with their rubber tires, have no such metal contact point on the ground and thus need two wires to complete the circuit- one a live wire, the other a grounding (dead) wire. The grounding wire is usually the one closest to the sidewalk.

A trolley does not contain an engine or transmission, in the traditional senses of those words; there is simply a series of circuit boards inside the coach which direct power to a single gear. The “gas pedal,” called a power pedal, is less like a gas pedal than a rheostat. Like a dimmer on a light bulb, you press it to adjust the amount of current being poured into the gear connecting to the rear axle. If you floor it, you’re dumping 750 volts into the rear wheels, and you can fly up the steepest hill in the network– that would be the Queen Anne counterbalance, at 18.5 degrees– without a hitch (James Street is a close second, at 18.3 degrees. Why does the bus go so slowly down these hills? Simply for safety. Trolleys and diesels have a speed limit of 10mph downhill on these segments, to avoid plunging into Puget Sound. Buses weigh at least 30,000 pounds, after all!).

Trolleys, like public transportation in general, are much more popular outside the US. Only six cities in North America have a trolley system. In order of size, they are: Vancouver, B.C., Frisco, Seattle, Dayton, Philly, and a couple lines in Boston. Hilly cities benefit most from a trolley network. A trolley’s torque is dramatically stronger than any conventional diesel engine, and thus they can handle hills much more easily. You’re not shifting gears with an internal combustion engine, waiting around to get up speed– rather, you’re just shoving current into that single gear, already flying. The agility with which they can take the hills is pretty astonishing, given how accustomed we are to large things in general always moving slowly. It’s also worth pointing out that the added torque and better braking lend themselves to superior performance on flat stretches as well.

Why are trolley bus brakes better? Trucks and diesel buses are equipped with engine retarders, which slow down the engine when you’re coasting, so the regular air brake, called a service brake, doesn’t have to do all the work of stopping such a huge vehicle. Trolley buses have “Dynamic Brakes,” which are a step up from retarders; they perform the same end function, but rather than slowing down the engine, they actually reverse the thrust of the motor. The generator circuits of the traction motor are loaded down with electrical resistance, resisting the rotation of the generators and thereby slowing down the rotation of the wheels. Reverse thrusters are used to slow down airplanes. Is that better than a normal engine retarder and service brake? Abso-friggin-lutely. It also minimizes wear on friction-based braking elements, allowing the service brakes to last longer.

Nathan Vass is an artist, filmmaker, photographer, and author by day, and a Metro bus driver by night, where his community-building work has been showcased on TED, NPR, The Seattle Times, KING 5 and landed him a spot on Seattle Magazine’s 2018 list of the 35 Most Influential People in Seattle. He has shown in over forty photography shows is also the director of nine films, six of which have shown at festivals, and one of which premiered at Henry Art Gallery. His book, The Lines That Make Us, is a Seattle bestseller and 2019 WA State Book Awards finalist.