If you’re into maps and data as much as we are, you’ll probably love this new series of maps made by the National Trust for Historic Preservation (NTfHP). NTfHP has an excellent series of maps relating to historic preservation called Older, Smaller, Better which range in themes like number of women-/minority-owned businesses, character score, and percent of non-chain businesses. The map themes compile data from a variety of sources like Yelp, the City of Seattle, and the King County Assessor to establish information on the parcel level and then aggregating that into square blocks to visually represent the data. These blocks are not necessarily contiguous with Census blocks or tracts nor actual city blocks. Currently only three US cities are covered in the map series (Seattle, San Francisco, and Washington, DC).

To give you a taste of the map series, we chose three different themes: medium building age, number of businesses, and number of parcels (granularity).

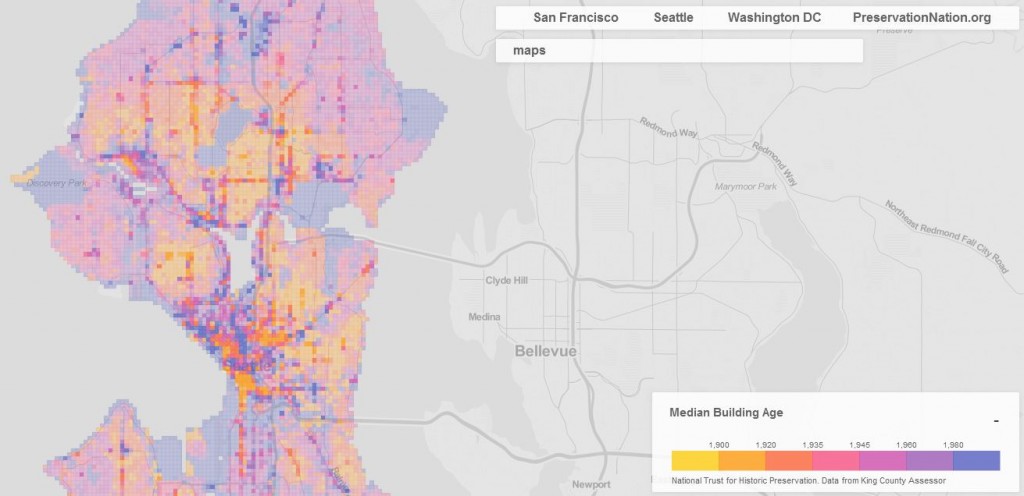

Median Building Age

In the map theme for Median Building Age, you’ll notice that it contains a range of color intensity for each set of years. The most intense colors appear along primary streets and urban villages in Seattle when compared to single-family residential areas. Presumably, this is indicative of the strong presence of buildings for a particular age within blocks. The map is probably as you’d expect: the closer in to the city center, the older the average building is. Of course, there are tons of pockets within the closer-in neighborhoods that have lots of new construction like Ballard, South Lake Union, Uptown, Pike/Pine in Capitol Hill, and First Hill. This shouldn’t come as a surprise to anyone.

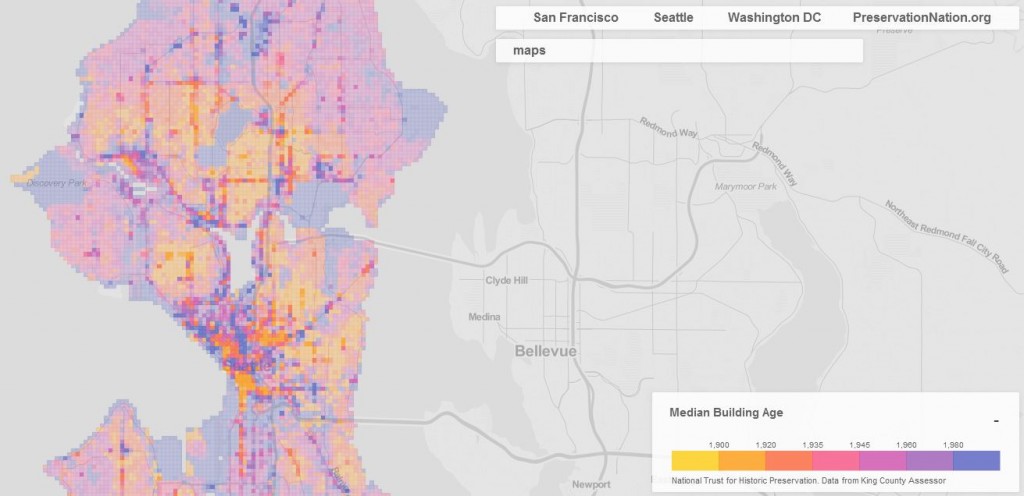

Number of Businesses

On a per block basis, most businesses are located in the central portion of Seattle like Downtown (one of them has over 900!), and to a lesser extent in urban villages and along primary streets. For fairly diverse neighborhoods like Wallingford, it’s still hard to compete with Downtown on a business density scale. Simply put: skyscrapers can easily contain over 100 different businesses whereas your average neighborhood block of lowrise mixed use can only contain a few.

Without looking too deeply at the data, we can safely assume most of the businesses Downtown consist of office type businesses as opposed to restaurants or direct retail services. Indeed, Downtown has plenty of the latter, too, but this actually makes up small portion of the total commercial square footage. This is an important dynamic to note when comparing areas of the city that are much more oriented to providing retail services as opposed to professional office services.

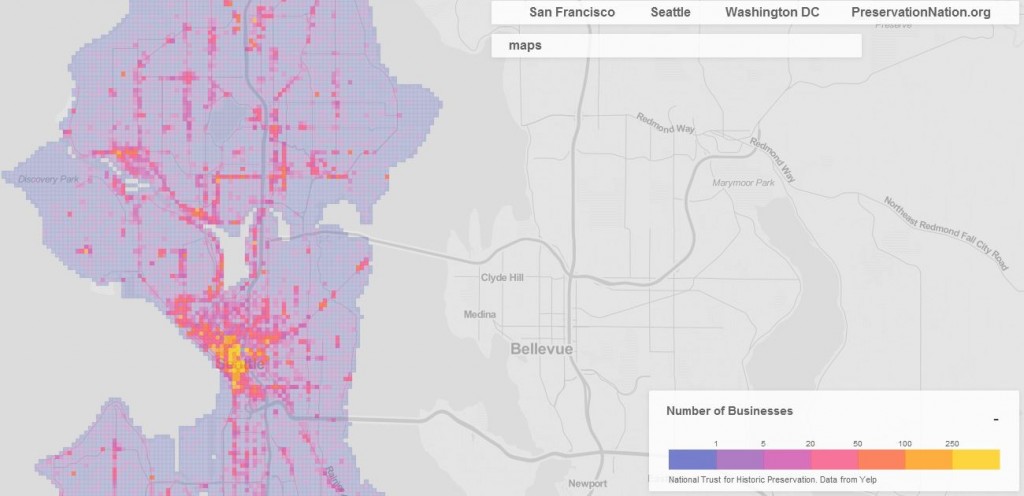

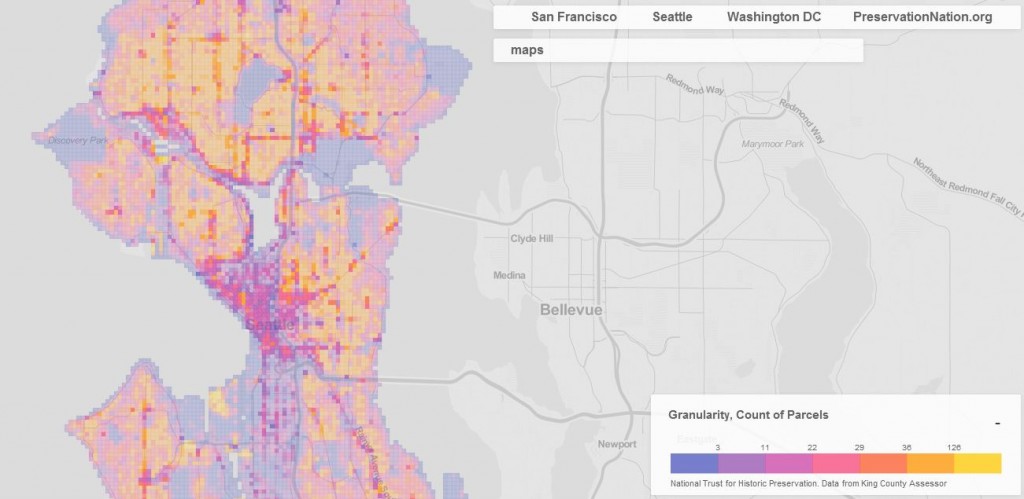

Granularity

The granularity metric looks at how many parcels exist per block. It’s an interesting look at the city, albeit a rough one. Areas that we know to be multi-family residential, mixed-use, or commercial in nature tend to have fewer lots per block. Meanwhile, the single-family residential areas can be cast into two broad categories:

- Older, closer-in neighborhoods to the city center have many lots which are necessarily small in lot size; and

- Newer, further to the fringe neighborhoods of the city (or areas of the city encumbered by critical areas) have fewer lots which are necessarily large in lot size.

Strictly looking at the map, it would be easy to assume that one lot equals one building, and hence many lots will result in many buildings. It’s not a one-to-one ratio. Granularity is much more nuanced because some lots have many buildings while other lots have no buildings. What we can learn from it is the general ownership of fee simple land on a per block basis. Are there few or many property owners of lots?

Stephen is a professional urban planner in Puget Sound with a passion for sustainable, livable, and diverse cities. He is especially interested in how policies, regulations, and programs can promote positive outcomes for communities. With stints in great cities like Bellingham and Cork, Stephen currently lives in Seattle. He primarily covers land use and transportation issues and has been with The Urbanist since 2014.